The Octoroon is a 19th-century melodrama by Irish playwright Dion Boucicault that tells the story of a young woman, Zoe, who passes for white but whose “single drop” of black blood condemns her to being sold as a slave.

An Octoroon is a 21st-century refraction of Boucicault’s play by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, an African-American playwright whose plays often center on questions of how historical representations of race continue to wield social power and cultural influence. For example, in his 2010 play Neighbors, he used blackface minstrelsy to explore questions of black identity, pride, shame, and self-loathing. In the many-faceted An Octoroon (which premiered at Soho Rep in 2014), it’s the melodramatic treatment of race and race relations that comes under scrutiny, and in particular the way that melodrama–with its display of suffering within a moral universe that punishes the bad and rewards the good–has historically structured, and continues to inform, the American imaginary.

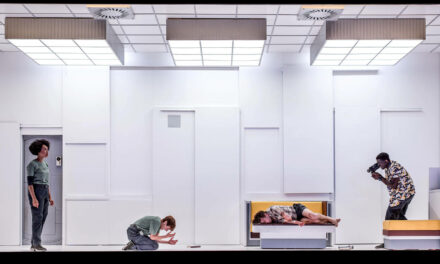

That scrutiny starts with a prologue in which an actor playing “BJJ” (Ananias J. Dixon), wearing nothing but white underpants, frames his adaptation of The Octoroon as a therapeutic exercise, as his (that is, Jacobs-Jenkins’s) attempt to grapple with the question of what it means to be a “black playwright.” Among the challenges he lists is the fact that white actors refuse to play racist oppressors in his plays (this, apparently, is based on a true experience), which explains why BJJ starts to apply whiteface makeup: his “therapist” (who may or may not be real) has suggested that he plays the white parts in his play himself. At some point in the middle of this comic rant, “The Playwright”–that is, Dion Boucicault, played by Martin Giles–appears, in an identical state of undress. The two face off–literally, in this production–and then, in a mirror image of the first part of the prologue, The Playwright launches into his own tirade, mostly about his vanished legacy, all the while putting on redface makeup in order to play the part of Wahnotee, the Native American character in The Octoroon (a role which Boucicault apparently took for himself for the beginning of his play’s original run). Race and racial casting are a subject of The Playwright’s monologue as well: where BJJ complained about not being able to get white actors for his cast, the Playwright is glad that “you can actually use negroes in your plays now…you really save a lot on makeup.” But because the budget can only afford “three negresses,” he’s recruited his Assistant, played by Parag S. Gohel, to take on the remaining black parts. So, by the end of the prologue you’ve got a black actor in whiteface, a white actor in redface, and an Indian actor in blackface, all about to participate in a melodrama that has a plot revolving around a definition of race that has to do with “one drop of blood.” Got it?

Ananias J. Dixon as M’Closky. Photo by Rocky Raco, courtesy Kinetic Theatre Company.

This emphasis on the performativity of race is but one of the devices Jacobs-Jenkins puts into play in his attempt to interrogate how we think about, and represent, race on stage. Another comes when the melodrama proper begins, and a curtain opens to reveal two slave women, Minnie (Melessie Clark) and Dido (Kelsey Robinson) at work. A projection tells us that none of us knows what slaves sounded like, and Jacobs-Jenkins’ solution is to endow these two with the language and demeanor of a couple of young African-American women from our current day. They gossip about other slaves on the plantation with the same kind of prurient and disaffected Schadenfreude you might overhear on a bus or at work, and the contrast between their manner of speaking and the content of their conversation is simultaneously funny and horrifying, particularly when it comes to the nonchalance with which they allude to the ever-present threat of sexual violence. In the course of a conversation about their new master George, for example, Minnie muses briefly on whether or not she would “fuck him” and then, after a pause, notes, “But I kind of get the feeling you don’t really get a say in the matter.” Where Boucicault erased the reality of slave life in his original play by sentimentalizing the relationship between white slaveholders and the people they enslaved, Jacobs-Jenkins uses anachronistic language to comment ironically on that erasure.

Minnie and Dido’s casual banter is further contrasted by the broad, over-the-top mode of performance that kicks in for the reenactment of The Octoroon itself, in which Dixon plays both the white hero and the white villain; Gohel plays two black slaves, both with cringe-inducing stereotypical shuck-and-jive; Giles is Wahnotee, a grunting Native American; Jenny Malarkey plays Dora, a rich Southern Belle; and Sarah Hollis is Zoe, the “Octoroon.” The plot of the melodrama centers on the villain M’Closky’s scheme to take over ownership not only of the plantation but also of Zoe, who believes herself to be a free woman. Dixon is terrific playing both the effete George (not just in white face but also in “white voice”) and the mustache-twirling M’Closky, and Malarkey is a comic confection as Dora, a perfect mix of high artifice and dripping “sincerity.”

Director Andrew Paul has done a good job of putting air quotes around the action within the melodrama, making visible the offensiveness of attitudes and language that an earlier era would have taken for granted. Often those air quotes render something funny that shouldn’t be, yielding moments when your laughter sticks in your throat. But the play also provides some unambiguous comedy, particularly in the bravura scene in which the hero George fights mano-a-mano against the villain M’Closky, which requires Dixon to fight himself. Props to fight director Michael Petyak and costume designer Kim Brown for making that moment a theatrical coup.

There are many other dots that Jacobs-Jenkins throws out for connection in this play, more than I have space to describe in this short post, and I’m not sure I could connect them all anyway (I’m still trying to figure out how Bre’r Rabbit fits into the whole thing). An Octoroon is a complicated play, and it’s also a rather messy one, presumably deliberately so. Jacobs-Jenkins claims that he doesn’t “know how blackness onstage works,” and his play doesn’t so much seek to figure that out as to demonstrate that the representation of race on stage has been, and will continue to be, an ongoing challenge.

This article was originally posted in The Pittsburgh Tatler on February 20, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Wendy Arons.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.