Teatro Argentina in Rome is currently sold out for the run of Odissea a/r, the new show by Palermo native director Emma Dante with students from the Scuola dei Mestieri dello Spettacolo of Teatro Biondo. The event is peculiar because none of the actors on stage is famous, as the cast is made of young performers who finished a three-year training under Dante’s direction. What is attracting flocks of spectators, season subscribers and young ones alike, is actually the fame that the director has conquered for herself in the last ten years or so.

The show plays the known story of the Odyssey. However, the original script does not refer to Homer’s lyrics at all. Instead, Odissea a/r represents Mediterranean culture (that is to say Sicilian culture) through a compelling and extremely enjoyable visual style made of a few simple props and the actors’ bodies, a signature style of Emma Dante. From Zeus, a bodybuilder in a skimpy red speedo, to the use of a blue plastic bucket to signify the sea, the play moves quickly from scene to scene, to talk about trust and complicity. In the past, hundreds of theatrical adaptations of Homer’s epic have focused on Odysseus’ journey. In Odissea a/r, the voyage is limited to a musical number where performers mime the action of rowing in a fashion that is very similar to tourists line dancing in an exotic resort. In fact, Emma Dante is not interested in the heroic and lonely figure of Odysseus, lonely because heroic and vice versa, but rather, she wants to comment on the collective value of theatre-making as an example of community.

For ninety minutes, all twenty-three actors (ten men and thirteen women) create and dismantle perfectly choreographed scenes. They create and dismantle, just like Penelope weaves her cloth in the day and unthreads it at night. The literal cloth is a 300 meters long black veil which actors pull across the stage turning it into a dark web that covers up Penelope like a grave, and tangles up her son Telemachus in a labyrinth. Faithful to her style, Emma Dante brings her native Sicily on stage through many references. The language, first and foremost, a Sicilian dialect is interspersed with standard Italian to enhance the comic value of a dialogue or differentiate the emotional condition of a character. Since Homeric poems were meant to be sung, oftentimes the actors embrace instruments and sing, but all choruses are also in Sicilian.

The most interesting ways to represent the island are the visual ones. For instance, Penelope appears on stage as a traditional mourning woman covered from head to toe by heavy black veils; the finale is propped up as a colorful and kitsch wedding party that one could easily be invited to in Palermo; Penelope’s female servants break into belly dancing as Sicilian culture derives from Arabic roots too; and finally, the ending is a heightened fight sequence in which Odysseus and his family, with a mafia attitude, massacre the people who have been occupying the palace for over three years.

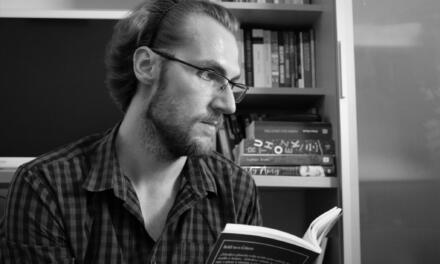

Odissea a/r, directed by Emma Dante. Teatro Argentina in Rome. Press photo

For those familiar with Emma Dante’s previous work, and especially with Le sorelle Macaluso, parts of the show may appear as a déjà vu: actors undressing on stage to almost full nudity and redressing up, the costumes’ colors going from black and white to bold colors and back, and the gymnastic training of the performers who showcase lots of stamina. The only short-coming of the show is probably the overburden presence of Emma Dante as director; the strong and enthralling visual elements often putting in second place the dialogue and the

The only shortcoming of the show is probably the overburden presence of Emma Dante; the strong and enthralling visual elements often place in second place the dialogue and the storyline. Nonetheless, the buzz around Odissea a/r is well-deserved, as Emma Dante has placed herself in the footsteps of those who, from the late 1960s, were decisive in importing in Italy the idea of the director as the conceptual and creative mind beyond a show: Giorgio Strehler and Luca Ronconi, in the first place. The uniqueness of Dante’s case is that, this time, there is a woman in charge. Oddly enough, in the Italian theatrical world, this is still a rarity.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Raffaele Furno.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.