Before the audience of the play 3sisters, with their eyes wide open, a music box, the girls on film, the Yugo-wave, the empty space, and the Chekhov of the future are embodied. The direction of the play completely shatters Chekhov’s text in order to rediscover it anew. One, two, three sisters. Let the fourth act replace the first, says this performance. Let the map of Africa from the play Uncle Vanya be replaced here by the happy, therefore nostalgic landscape of the former common land of the Western Balkans. Let that be a metaphor. The lake in front of which the stage stands in Chekhov’s The Seagull becomes here a river. An idea for a short story becomes a verse from a song. Tuzenbach (Kőrösi István) sings the lyrics of the band Haustor that we all love in these parts: “All my life I’ve been dreaming of leaving along the river, on an old steamboat carrying salt, and of taking with me an old, never-forgotten love, a thin, long cigar and a pair of golden spurs…” In this play, it is not the actors playing dramatic characters who mourn, suffer, or daydream, but the audience. The ironically perceived “fingers of the artist” Lopakhin (from The Cherry Orchard) here become the fingers of Kuligin (Szalai Bence), who deftly and skillfully plucks the strings of an electric guitar. Chekhov’s pistol in the play before us remains without bullets, but it fires Bengal flames of emotion and strikes straight to the heart; it kills.

How do new times read Chekhov?! The prediction of “creating empty magnitudes” and the collapse of social illusions are evident in the characters of the play Uncle Vanya. The new forms, the new shapes defended by young artists in The Seagull, are also defended by the new times. The sound of The Cherry Orchard being cut down heralds the destruction of everything old, everything past — a complete break with tradition for the sake of a new age. And now, at the Novi Sad Theatre/Újvidéki Színház, 3sisters, directed by Botond Nagy, becomes the manifestation of all of the above. In Chekhov’s theatre of the future, the harsh realism of the present hides. Between the lines — nothingness. The general theme in Russian literature at the end of the Golden and the beginning of the Silver Age, the intelligentsia, is thoughtfully replaced on stage in this production by the general emptiness of a new space, a new time, and powerless people. All of this, the adaptation of 3sisters bravely carries. Moscow, which does not believe in tears, never reached, yet always dreamed of and promised land of Masha (László Judit), Olga (Banka Lívia), and Irina (Figura Terézia) — does not exist. In the background, there is a mosaic, in the shadow of palms, a hidden oasis of a sunny and lost Yugoslavia. Did it ever exist?!

3sisters (2025) directed by Botond Nagy at the Novi Sad Theatre. Photo: Andrei Văleanu

A specific adaptation of a dramatic classic, based on postdramatic postulates and procedures, touches the very essence of hopelessness, passivity, and imagined (or rather invented) nostalgia that paralyses the characters in the play, as well as the faces of the audience members. The phenomenon of loneliness, alienation, and helplessness places the characters in a scenography of cabins of sorrow and suitcases of love, those lost, missed, never reached. Characters are in aquariums, or beer crates, vodka bottles, in emptied, like fish out of water, completely vacant swimming pools, in an attempt at escapism. The act of escape takes place in liminal, even more claustrophobic spaces. A person places themselves in cold refrigerators with the writer’s picture taped to them, in plush costumes, in eternal bars. People close themselves off in personal terrariums with a gramophone and the records they love. The gramophone becomes a symbol not of an era, but of a diagnosis. At the beginning of the 20th century, “gramomania” appeared as an obsession with recorded music, accompanied by a fear of social isolation and passivity. The words and tones from the gramophone become white noise, the fear of failed survival in this time of our spiritual paralysis. The promised odyssey of the twenty-first century may be a flight that never happened, nor ever will — a tomorrow that never came. A final departure, but into complete oblivion.

3sisters (2025) directed by Botond Nagy at the Novi Sad Theatre. Photo: Andrei Văleanu

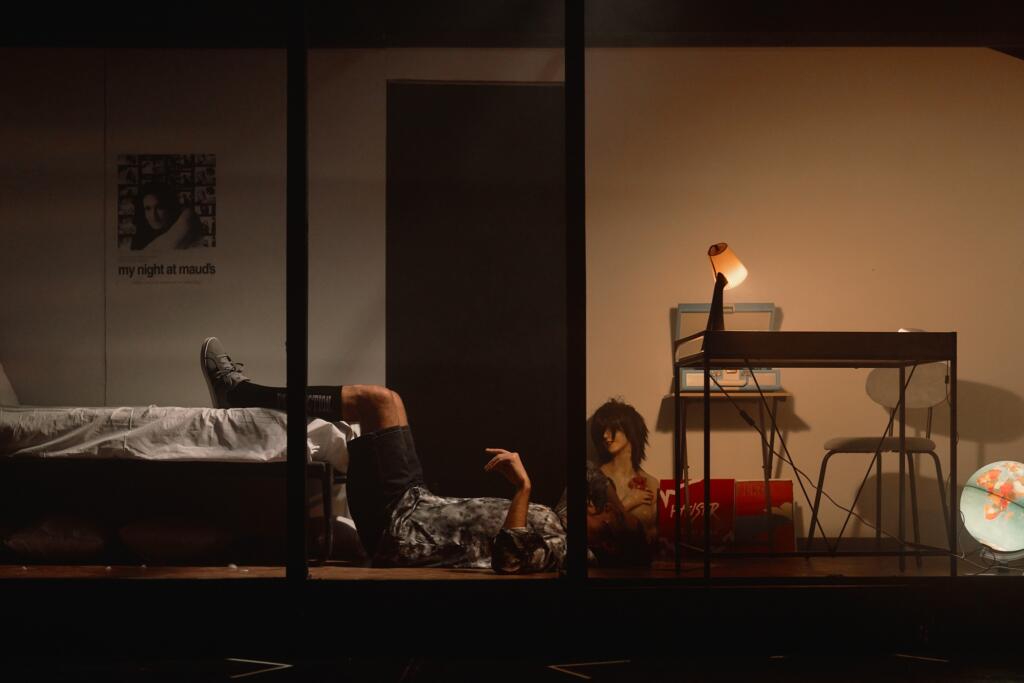

Life in a box, the man in a case: each actor without a rudder, isolated because of an uncertain tomorrow, sinks into the thoughts of the moment. Everyone hopes that before them a crack in the future will open, or a slit through which they might pass, escape. Videodrome. The theatrical image of stagnation is shattered through these new forms. New forms in the play appear through the, no longer so new, art of film. This concept is realised on stage through the brother Andrei Prozorov (Mészáros Gábor, guest appearance), who does not grow fatter but taller. A man with a movie camera, he dreamed not of the scientific career Chekhov envisioned for him but of becoming a film director who now films weddings. Chekhov’s symbol, that tiny detail revealing the broader picture, becomes a close-up shot of the camera. It alludes to My Night at Maud’s and Pulp Fiction. Once again, the perceptions and receptions of time and space mix, as do those of the characters. Opposite the marble busts of philosophers stands a plastic mannequin from a boutique. On stage, there is a sign, an emergency exit instruction, but no one dares to go anywhere… no one even truly tries, while domestic musical hits that marked an already long-lost time and space spin and deafen the room.

3sisters (2025) directed by Botond Nagy at the Novi Sad Theatre. Photo: Andrei Văleanu

The directorial play is effective; the image of the world is presented through symbols. The fire from the third act, which is to burn down a third of the town, becomes a cigarette break. Helpless, paralysed in his attempt to change, in a wheelchair, the actor Pongó Gábor, who plays the character of Vershinin, carries on his paralysed legs the impossible, hopeless love and countless murderous wars. Each character has their own action figure on a small table, among the broken glasses and plates. The suggestion is clear: one must live, live consciously, live freely. And stitch happiness into old little flags, to work.

The indisputably talented acting ensemble of the Novi Sad Theatre, combined with a precious and unusual directorial approach, builds a distinct story of a new theatre of abstract forms or a transitional performance toward the theatre of the future. The dramaturgy, due to constant shifts in time and space, drastically deviates from the original version of Chekhov’s play. The light design announces the apocalypse, while the musical compositions strike directly into a soul overwhelmed by nostalgia. The performance undeniably succeeds in creating precisely that feeling between the past and the future — a space in which the present does not exist. Intentional modernism, claustrophobic scenography, and fast-fashion costume design are the only elements that remind us of the present and that could serve as connections of the unconnectable.

3sisters (2025) directed by Botond Nagy at the Novi Sad Theatre. Photo: Andrei Văleanu

But Chekhov himself gives the director and the actors of this performance the right to push the boundaries of theatre, if no other progress is possible, with the words from the play:

“In two or three hundred years, life on this earth (and likewise on stage) will be gorgeously beautiful and glorious. Mankind needs such a life, and if it is not ours today, then we must look forward to it, wait, think, prepare for it.”

As with Chekhov, music is heard in the background, and what is most important, most essential, and most emotional always takes place offstage, out of the audience’s sight. Thus, this performance, too, ends with a song by the most famous singer-songwriter of Novi Sad city, Đorđe Balašević — while behind the stage and in front of it stands life, reality, not a former country but the present one: the one that, over the past year, has been actively resisting collapse.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emilija Kvočka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.