The Rudolfinum is the main classical music performance hall in Prague. The house of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra is a grand neoclassical building sitting proudly on the banks of the Vltava. Statues of important composers form an architectural crown on the building’s top, and on the ground, one of Antonín Dvořák, perhaps the most influential Czech composer and also conductor of concerts there, faces visitors as they come out of its doors.

We, however, were sitting near the side entrance, the shaded path that opens to the Rudolfinum Gallery. The performance we were there to see wasn’t in Dvořák Hall. It was out here, on the sidewalk. And there wasn’t any music either, per se. The only instruments were sheets of plastic, plus the sounds of the street – cars, pedestrians, a phone ringing, and on the other side of the building, a massive crowd cheering for the Prague Tyčka, a pole-vaulting event with all the subtlety of a can of Red Bull.

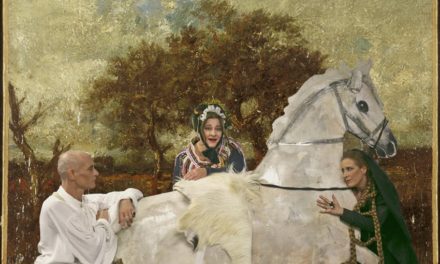

The performance was Inhabiting Noise and Silence, part of the Prague Quadrennial, naturally. A collaborative project out of México, it was conceived and designed by Laura Martínez, and performed by Carol Cervantes and Diego Cristian Saldaña. It was fresh and creative in the best way – making the audience rethink what fundamental concepts like music, costume, and dance really means. Because the music, costume, and dance were all provided by the sheets of plastic I referenced earlier. Stitched together in an unexpectedly beautiful and complex way, with accordion folds, buttons, and zippers, the material was nevertheless unmistakable. In the center, there is thicker plastic like a shower curtain, from which billows a train of thinner pieces like plastic bags. The whole thing is an architectural wonder. Because the performance takes place on the street, the materials get visibly dirty. It’s trash, reimagined.

Photo by Barboba Bahlsenová

A lot of the performance had to do with showing the potential of these pieces, which I’ll call costumes. Spinning them to hear the air pass through the vents, bunching them up to hear them crunch, blowing them like whistles made out of blades of grass, wearing them like magnificent ceremonial capes, shaking them on either side of the body like a toreador to his bull. At one point, Cervantes and Saldaña sat on the floor and just worked the zippers up and down, creating with this simple action both sound and movement in the splayed-out costumes. The two performers seemed to maintain eye contact at all possible moments. When Cervantes climbed on Saldaña’s shoulders, both of them wearing one, they looked like a giant jellyfish. When they clipped the two costumes together, it looked like a giant ruffled collar for a monstrous Victorian schoolmarm. Cervantes stood in the middle fluffing up the sides until they stood like walls. Saldaña then walked around it and stamped it down. But the costume was resilient. Soon it was back up in the air, twirling like a snowflake.

The audience sat on the steps of the very open gallery. Once the performance began, everybody entering and exiting the building became involuntary participants, like the gaggle of music school boys who embarrassedly carried their instruments across Carol and Diego’s stage as they left class. At one point, the performers tossed the costumes into the audience, with the greatest of ease. Throwing them back was less easy. It required incredible control and strength, we learned, to manipulate these gracefully.

Photo by Barboba Bahlsenová

Towards the end of the show, the costumes made their way into the audience and stayed there. The performers plus the director taught us how to “play” them, whistling, scrunching, tapping out a rhythm. Then, the audience was invited to come down off the steps and take the costumes out for a spin. More awkward than heavy (this phrase was the name of an art show by the Ink Tank collective Austin, Texas in 2013 and I think it should become a common saying), they took some getting used to. When two people tried to share one, I noticed, it only worked when they were friends. The communication, the intimacy Cervantes and Saldaña brought to the performance were translated into their ease with these costumes. Two strangers on either end of a big stack of plastic bags looked like they were both playing, but two different games. But when you put one on yourself, it was transformative. You could be a flamenco dancer, or a shaman, or a swan, or a small child who would rather play with the gift box than the gift. The performance attuned us to these possibilities, and shifted perspective, at least for me, irreversibly.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.