The weekly meetings of the Phoenix Players Theatre Group (PPTG) always begin and end with an outpouring of goodwill, perhaps remarkable considering the setting. The members of the ensemble are tremendously open, emotionally and intellectually. Shoulder bumps and warm handshakes are exchanged, and gratitude is freely offered. Following the greetings, we all chat informally about news inside and outside the prison walls. On one memorable occasion, we talked about how a cellblock had been locked down for an investigation into an alleged suicide. More often, we talk about our families. We then gather into a circle, with the civilian volunteers evenly dispersed among the incarcerated ensemble members. In unison, the group recites the motto:

We are a community of transformation.Through the power of self-discovery,we create the opportunityto know and grow into ourselves.

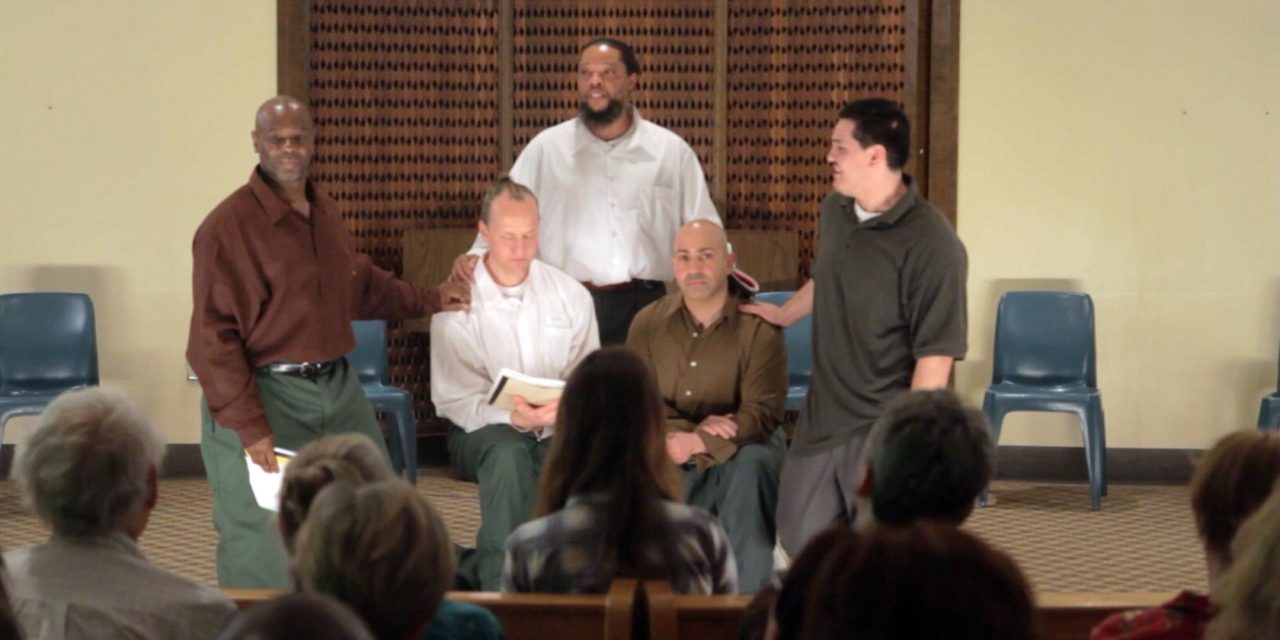

In 2009 Michael Rhynes and Clifford Williamson, incarcerated men in the Auburn Correctional Facility in central New York, founded the Auburn Phoenix Players. Shortly thereafter, the two renamed the company to form PPTG. They did this because they both realized that, while they were “in” Auburn, they were not “of” Auburn. In the founders’ own words, “PPTG is a grassroots program developed by and for incarcerated persons and communities in a maximum security prison. It is a transformative theatre community, which utilizes theatre to reconnect incarcerated people to their full humanity.” [1] Even though the group invites several civilian facilitators into its meetings, PPTG is run and operated by incarcerated people. Every Friday evening the group’s civilian facilitators venture into the prison and the incarcerated performer-writers venture out of their cells to meet in the Osborne Schoolhouse located inside Auburn’s walls. Together, they devise theatre pieces, rehearse scenes and monologues, discuss current events, and share personal stories. Over the past several years, PPTG has developed an audition, training, and rehearsal sequence spanning a year and a half, culminating in a performance for an invited audience of about 80 non-incarcerated people.

One of the group’s key concepts, transformation, works in two directions: It originates within the participants to repair and restore the aspects of their humanity fractured in incarceration, and at the same time it works from without, helping to alter public perception of the people reductively marked “criminal.” By creating space for its incarcerated members to use the body in ways not usually permitted in prison, PPTG encourages them to stretch outside the paradoxically uncomfortable comfort zone of punitive incarceration, and to reach their full potential as human beings—both in the eyes of non-incarcerated society and of the participants themselves. Transformation is a common goal for prison theatre groups, and for PPTG transformation is a communal practice, a recurrent process one undertakes with others. In distinction from the stated rehabilitative mission of the New York State Department of Corrections, the transformation that occurs in PPTG does not assume a mechanical return to a population of self-possessed and productive “normal” citizens, a false promise if there ever was one. PPTG’s transformation comes from within and is undertaken daily and by all those who wish to participate. It is not only the “offenders” who transform, but all those willing to bear witness to the group as well.

Witnessing is a critical concept for PPTG. Through the sharing of stories and experiences that spread outside Auburn’s walls the incarcerated members of PPTG endeavor to open in the minds of the public alternate perceptions of themselves and of incarcerated people more generally. The authors of this article create, perform, and explore alongside PPTG, and so we’re uniquely poised to bear witness to the group. [2] Whenever a new facilitator or visitor enters the group, the men love to question the newcomer, asking why they have come and what image of prison they carry with them into the facility. PPTG members are interested in learning about the newcomer’s preconceived expectations of the prison so that they can better understand how incarcerated people are viewed in the outside world. It’s important to mark when a visitor crosses the prison threshold, an act that many will never experience, so that when that individual leaves, he or she can carry the experience out and bear witness to the wider populace. One of the founding members, David, even kicked off the group’s 2014 performance An Indeterminate Life, by interrogating the audience in a similar vein:

First and foremost I want to thank you all for coming tonight . . . I also want to thank you for putting up with metal detectors, pat downs, blood work and questions such as why you come this old creepy institution that confines a lot of “bad” people . . .I have a question for you. Have you ever been to prison before? Well, in case you didn’t know, I have . . .I mean who gets excited about going to prison . . .And some of you are probably like: “No, I’ve never been to prison before . . .” If that’s the case, well now you can check this off your to do list: go to prison. Check. Strange to do list.

At the beginning of each workshop cycle, the group vets new members via a six-page application, which are carefully distributed to potential recruits by senior members. Applicants provide general background information, as well as information more specifically applicable to PPTG, such as their interests in theatre, transformation, and the group itself. Some of the questions are meant to elicit just how prepared a potential member is to honestly interrogate his own incarceration and to assess his transformative goals. Questions ask what therapeutic, educational, and vocational programs they have taken. In addition, applicants are asked to describe themselves before entering prison, and how incarceration has changed them. Applicants are also asked to discuss any prejudices that might prevent them from working with a specific group or individual, depending on factors of culture, race, gender, or sexual orientation. Thus far there haven’t been any issues in the group. In fact, the situation is just the opposite. PPTG offers an astonishing system of support, considering the hyper-masculine environment. After reading through all the completed applications, the group discusses how compatible each applicant might be with PPTG. Because the applicants have already been carefully selected, most will be invited to move forward in the process, pending review by the prison administration.

In the second phase of the process, applicants embark on a six-week orientation workshop planned and led by the more experienced members. Leading the exercises and theatre games helps PPTG members to gain confidence in their creative abilities and to obtain a sense of ownership over the process. These exercises allow the new members to dip their toes in the PPTG water, so to speak, becoming acquainted with one another and learning the group’s ensemble theatre vocabulary. During the workshop, after each exercise and theatre game, the group spends time reflecting on its purpose, meaning, and experience. These conversations further encourage the sense of community vital to PPTG. In the latter weeks of the workshop, the group ventures into more challenging and risky territory.

In one of the most uncomfortable exercises from the final weeks of the workshop, the participants break into pairs and stand facing one another. One partner shuts his eyes while the other partner pulls an exaggerated facial expression. The latter partner then places the blind partner’s hands on his face with the aim of teaching through touch what the face “looks” like. The blind partner then mimics the face he feels. This exercise performs the sort of blend of theatre and therapy that is one of PPTG’s main goals. It’s one of the first times that the group introduces the potential new members to the practice of collective vulnerability that is central to the group’s mission. As Rhynes writes, “We seek not to make every man in this prison a professional dramatist, but to reconnect us to society, our communities, and our families, by learning through drama how to love, what it feels like to be compassionate, to forgive and be forgiven, to reach into the depths of our beings and bring forth our humanity.” [3] In this exercise the touch embodies the pedagogy of empathy that Rhynes describes. In the touch of faces, one must lower one’s defenses and reach through the defenses of the other. This builds trust—something that is difficult to do in prison—and contributes to the individual’s reconnection with his buried or forgotten tenderness.

The next phase of the process focuses on training in psychophysical techniques first introduced to the group by former Cornell theatre professor Stephen Cole and his daughter Paula, herself a theatre professor at Ithaca College. The first of these is loosely adapted from Alexander Lowen’s Bioenergetics. This text contains a chapter on the concept of “Characterology,” in which Lowen theorizes that an individual’s personality is formed through various defense mechanisms built in childhood, manifesting in physical tensions. [4] The group also trains in rasaboxes, first developed by performance theorist Richard Schechner in the 1980s and 90s based on the eight key emotions from the ancient Sanskrit text Natyasastra. [5] This work similarly focuses on undermining the so-called mind-body split, using physical exercises to help performers explore emotions. These techniques are obviously applicable to PPTG’s model of drama therapy, but the participants are also encouraged to not “psychoanalyze” themselves.

During this period, PPTG spends several months reading and discussing the above theories and then practicing them through physical and theatrical exercises. In the beginning, many of the exercises are exploratory: For example, the members of the group might meander around the room experimenting with how it feels to have all of one’s tension in the chest or in the feet. In later weeks PPTG’s exercises begin to incorporate more traditionally improvisatory and dramatic approaches. The performers blend the techniques with classic texts, such as excerpts from Masters’ Spoon River Anthology, or they write and perform original monologues based on the techniques. The importance of storytelling to the group becomes evident in this phase of the process. Since many of PPTG’s members have experienced and continue to experience in their incarceration the traumatic consequences of horrifying stories, the group attempts to engage with these narratives in order “to seek atonement for catering to [their] base nature,” as Rhynes says. [6] One of PPTG’s basic tenets is to help its members “atone for those human beings for whom [they’ve] caused so much pain and suffering […] to atone to society for not living up to [their] organic contract by loving and caring for neighbors […] to atone to [their] families for failing to reach [their] potential and their dreams for [them].” [7] This is accomplished through uncovering and interpreting stories that exist in the literary and dramatic canon, and also through approaching the past directly, using the aesthetics of performance to allow for reflection and personal growth.

This training phase, with its emphasis on trust and compassion, spontaneously provokes stories that are both stunning and heart-wrenching. Once, founding member Shane re-enacted the murder he committed, and then sobbed for his lost innocence, mourning his place in a system that doesn’t allow grief. In another session, Efraim told the story of his rushing to the hospital to be present for his daughter’s birth on July 4th. He described looking out over the East River in New York City and watching the fireworks as he held his baby daughter in his arms. This story was made all the more poignant by the fact that, at the time of the story’s telling, Efraim hadn’t seen his daughter in nearly two decades.

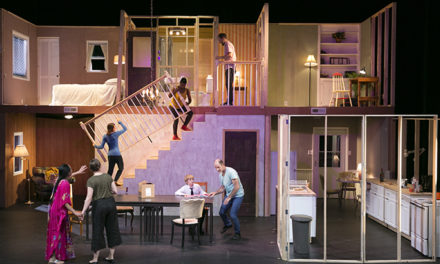

After the training phase, the group generates dramatic material in a concentrated way as it prepares for an eventual public performance. PPTG performances typically take the form of theatrical collage, blending together different pieces developed by the individual performer-authors. Many pieces are collected from earlier exercises and games. For example, if during training one of the members wrote or performed a particularly stirring monologue, then the group may choose to build it into a larger piece for performance. PPTG also uses writing prompts in order to generate performance texts. In response to one such prompt, each member of the group brainstorms the 10 most important events of his life. Telling a story about one or all of these may eventually lead to a piece, or inspire

another PPTG member to create a piece of his own.

The subject matter of the individual texts that make up a full PPTG performance vary. Some of the pieces deal with the experiences and realities of an incarcerated life, such as a scene Leroy Taylor wrote in response to a prompt for a life-changing telephone conversation, in which his son revealed that he had Googled his father and discovered his crime. Taylor’s confused son asks how he could have committed the crime for which he was imprisoned. Was what the news reports said true? In that moment, the audience shares Taylor’s shock and dread. Taylor, at first struck speechless, in the end, says, “I want you to learn from my bad decisions and see how I have learned from the wrongs and have made changes to be a much better man. Please remember how much I love you and that no one can tell you about your Dad because you know me for yourself.” [8] In this scene Taylor is able to come out the other side of this emotional exchange, and help his son understand that all people make mistakes—even fathers—and that one must learn from those mistakes.

Sometimes pieces deal directly with the events that led to the individual’s incarceration, which is demonstrated in Demetrius Molina’s poem “Story of Words”:

Showering drying dressing leaving.Driving arriving walking standing waiting.Paying entering ordering drinking talking dancing drinking.Buzzing laughing partying slurring drinking drinking.Sensing seeing tensing grouping watching.Waiting closing leaving avoiding warning yelling raging.Pushing pushing swinging fighting.Pulling aiming shooting screaming running shooting driving speeding hiding.Waiting hearing fearing disbelieving.Thinking regretting stressing blaming running hiding fearing.Crying praying pleading hoping.Packing leaving driving

Stopped caught cuffed arrested. [9]

This piece uses the present participle to evoke the twisting speed and confusion of the moments leading to Molina’s arrest. The sudden switch to the past tense in the final line represents the abrupt finality of that moment of capture. Molina aestheticizes the life-changing scenes leading to his eventual incarceration with verbs that members of the audience might easily identify with and understand. One realizes that it is only a series of actions that can lead to one’s conviction, and to think twice before judging the person who committed them. Molina confronts his crime in this piece, pushing himself to confront and take responsibility for his actions. This is a powerful and poetic illustration of PPTG’s brand of transformation, shifting attitudes and emotions from the inside and from the outside, on subject matter that might be too difficult to approach in another context.

PPTG spends the weeks leading to the performance honing the script and rehearsing stage movement and action. The volunteers invite audience members, composed mostly of prison educators, clearing their names with the Department of Corrections. These culminating weeks have been filmed as a part of the documentary Human Again, an unprecedented look inside Auburn Correctional at the final rehearsals and public presentation of PPTG’s work in the spring and summer of 2012. The final act of the PPTG process, this performance demonstrates and dramatizes the personal growth, intellectual insight, and sheer hard work of the men that put it together. As one audience member testified during the post-show talkback, PPTG’s performances make the world “bigger” and “better,” make the brain “smarter,” and lend meaning to the experience of being a human sharing other human experiences. [10]

1 “Phoenix Players Theatre Group.” Informational brochure. Auburn, NY, 2014. Italics in original. http://phoenixplayersatauburn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/PPTG-brochure_april–2015.pdf.

2 Much of this article previously published online: Fesette, Nicholas and Bruce Levitt, “Where the Walls Contain Everything but the Sky: The Birth and Growth of the Phoenix Players Theatre Group,” Rejoinder: An Online Journal Published by the Institute for Research on Women, Rutgers University, Issue 1, Winter 2016, http://irw.rutgers.edu/rejoinder-webjournal/marking-time/250-where-the-walls-contain-everything-but-the-sky; see also our forthcoming article “Pedagogies of Self-Humanization: Collaborating to Engage Trauma in the Phoenix Players Theatre Group” in Teaching Artist Journal, special issue “Free Time,” ed. Clare Hammoor, November 2017.

3 Rhynes, Michael. “Flames.” Auburn, NY, 2009. http://phoenixplayersatauburn.com/wp–

content/uploads/2015/04/PPTG–first-proposal.pdf.

4 Lowen, Alexander. Bioenergetics: The Revolutionary Therapy That Uses the Language of the Body to Heal the Problems of the Mind. New York: Penguin Group, 1994. 151.5 rasaboxes.org. “What is rasaboxes?” Accessed Jan 12, 2015. http://rasaboxes.org/about/.

6 Rhynes, 2009.

7 Ibid.

8 Taylor, Leroy. “Na’cir’s Google Search.” From An Indeterminate Life. Auburn, NY, 2014. http://phoenixplayersatauburn.com/nacirs–google-search/.

9 Molina, Demetrius. “Story of Words.” From An Indeterminate Life. Auburn, NY, 2014. http://phoenixplayersatauburn.com/story-of-words/.

10 Human Again. Dir. Bruce Levitt. 2016.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nick Fesette and Bruce A. Levitt.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.