Celebrated American actor Willem Dafoe, the new artistic director of the Venice Theatre Biennale, offered a clear statement about his aims for this year’s programme:

“I am an actor. My idea is not to present a retrospective of contemporary world theatre but rather an inquiry into the essence of theatre and the presence of the body. At a time in history when we rely more and more on artificial intelligence, I want to focus on the element of human endurance: the intelligence of the body. Theatre is body.”

Theatre is Body. Body is Poetry, the title of Dafoe’s Theatre Biennale, perfectly encapsulates these ideas. Among the international theatre-makers invited to Venice, Elizabeth LeCompte and the Wooster group, Eugenio Barba, Romeo Castellucci, Thomas Ostermeier, Milo Rau, Thomas Richards, and many others. Parallel to the shows, the workshops of the Biennale College, which welcome young practitioners from Italy and beyond, will likewise explore these themes. In an age, where the impact of technology and AI is growing alarmingly fast, a reappraisal of the quintessence of theatre – body, presence, poetry, ritual – is urgently needed.

The opening show, the Wooster group’s Symphony of Rats, brought back memories for me of an extremely vibrant period in my theatregoing. Richard Foreman’s seminal play premiered at New York’s Performance Garage in 1988 and continues to chime allusively and tantalisingly thirty-seven years on. Originally directed by Foreman and performed by the Wooster group, in 2024 the play was revived and directed by Elizabeth LeCompte and Kate Valka, with a cast of actors from the present-day Wooster group. Foreman, who died in January of this year, gave his blessing to the directors to make the play their own.

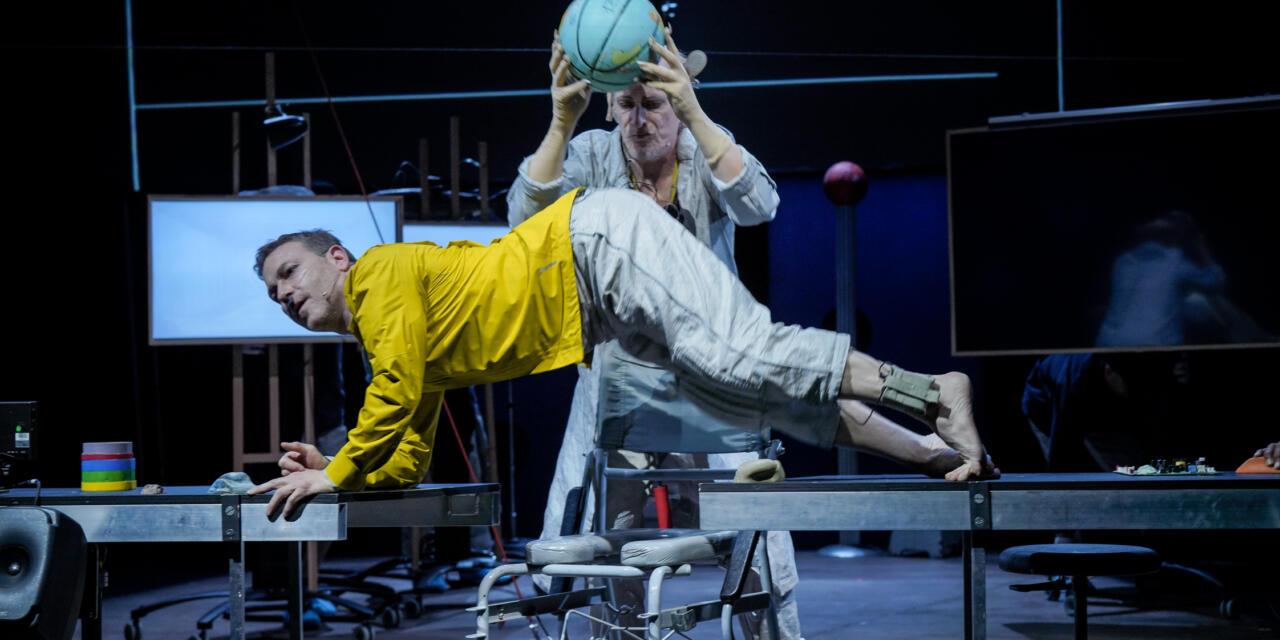

Symphony of Rats, by The Wooster Group. Photo credits: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Symphony of Rats dramatizes the hallucinatory nightmare of an unnamed President of the United States, who claims to be hearing messages from outer space. Early on, the President (excellent performance by Ari Fliakos) gives us a clue to the possible reason for his deranged state: a Covid plus flu booster gone wrong, signalling that the present production unfolds in the post Covid era. Dressed casually in an old tan top and yellow jacket, the President sits centre stage most of the time, flanked by a man, with large rat ears, and wearing a long lab coat, while another man speaks through a basketball hoop, now and then admonishing the proceedings. The President is forever on the move, pushed around in a wheelchair commode, as if to underline that he is not his own man, but ruled by others. Following the well-known aesthetics of the Wooster group, there is no linear story and little psychological realism, rather the action pans out seemingly at random. Onstage, multiple screens, most of which are empty, except one which shows film clips, including Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator. In another clip, we watch the actor, playing the President, fighting a bloody battle with his assistant, which ends in the former’s head being cut off by a digital line. The President’s conclusion pointed to his sadomasochistic streak: “I can say this makes me feel better.” Instead, many short sequences are performed onstage, such as the entertaining exchange between the President and his aide, who asks him whether he will ever get a grip on reality, offering him two tickets to Tornado-ville. The President quickly accepts, and soon after he can be seen brandishing a guitar and dancing, having succeeded in breaking ‘the wall of inhibition’ as it is defined. A string of songs, likewise, forms an integral part of this multimedia show, like The Ice Cream Man, the Ice Cream Brute, perhaps a satirical parody on Ironman’s 1970s lyrics as well as a raft of multimedia spinoffs. Thrown into the mix, there are literary fragments, such as William Blake’s Tyger, which sent out a chilling message, changing the tone of the performance, as it sombrely recalled the overarching evil in the world. Given the state of turmoil of today’s world, and the many figures in positions of power, who are grossly inadequate for the job at hand, Symphony of Rats presents us with that subconscious realm, a world of dreams and nightmares, which needs careful consideration as we observe and try to understand human behaviour.

Symphony of Rats, by The Wooster Group. Photo credits: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Year and length: 2024, 75’ (European premiere)

Text: Richard Foreman

Direction: Elizabeth LeCompte, Kate Valk

Created by: The Wooster Group

With: Niall Cunningham, Jim Fletcher, Ari Fliakos, Andrew Maillet, Tavish Miller, Michaela Murphy, Guillermo Resto

Set design: Elizabeth LeCompte

Sound design and music: Eric Sluyter

Video design: Yudam Hyung Seok Jeon

Light design: Jennifer Tipton, Evan Anderson

Additional lighting: David Sexton

Costumes: Antonia Belt

Assistant director and stage manager: Michaela Murphy

Additional sound and video: Andrew Maillet

Sound and video technician: Dan Dobson

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Margaret Rose.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.