Golden Thread Productions and Z Space’s world premiere of Pilgrimage, written by Humaira Ghilzai and Bridgette Dutta Portman, opened on October 26, 2025, marking the culmination of a years-long creative process that epitomizes the collaborative and politically engaged spirit driving the company’s 2025 Season of Solidarity. The two-act play follows four Afghan American women and a Black American Muslim woman convert as they embark on the sacred journey of pilgrimage to Mecca known as Umrah. Unlike Hajj, which is considered mandatory for practicing Muslims and occurs on fixed dates, Umrah is a lesser pilgrimage that can happen whenever a pilgrim decides to embark on the journey. First conceived during Golden Thread’s Research and Development Residencies in 2021, Pilgrimage has evolved through workshops and readings across the Bay Area—from an early staged reading at Z Below (2022) to Crowded Fire Theater’s Matchbox Reading Series (2023), and subsequent readings at Stanford and San José State (2024). Its world premiere arrives this year within a season that foregrounds interconnected struggles and shared histories across Armenian, Palestinian, and Afghan narratives, an act of artistic solidarity urgently resonant in our time. I attended the first preview performance on October 24 at Z Space, a prime spot in San Francisco for new work.

The play opened with the ritual act of purification before prayer in Islam (wuzu in Dari, a dialect of the Persian language spoken in Afghanistan; wudu in Arabic). The sound of running water filled the space as the performers methodically mimed washing their faces and hands. James Ard’s evocative sound design coupled with director Michelle Talgrow’s staging grounded the audience in the personal moment of each actor enacting the ritual with the collective—distinct in their gestural work, yet held together by the specific movements prescribed for this moment. Moving in tandem but not in unison, the profound simplicity of the shared ritual situated the world of the play within the sensory and spiritual worlds of faith and family.

At the heart of Pilgrimage lies Noor, played by Nora El Samahy, a devout Afghan woman in her sixties who gathers her daughter, Maryam, and nieces, Nadia and Sosan, to fulfill her late sister’s dying wish: that the family make umrah together. Joining them is Fatima, Nadia’s best friend and a revert to Islam. The central narrative focuses on Noor’s hidden past and her efforts to bring her family together. However, each woman has come on the journey to fulfill more than just the promise to the departed Khala /khaalah/ (aunt) Almas. They each harbor their own secrets, hoping to gain more than spiritual enlightenment from the journey; each is seeking something deeper, adding layers of complexity to their trip and family dynamic. El Samahy plays Noor with depth and restraint, and it is the character’s spiritual unraveling that anchors the play’s emotional terrain. Her daughter Maryam (Fatemeh Mehraban), a biotech CEO facing legal trouble, embodies the tension between material ambition and moral responsibility. Nadia (Leda Rasooli) and Sosan (Isabel Alamine) are sisters who seem to thrive by working against each other. Nadia clings to religious duty while wrestling with her impending divorce and the hidden aspects of her identity, and Sosan, the rebellious artist sister, wants to rediscover herself as both an artist and a member of the family. Fatima (Jeunée Simon) helped plan the trip, due to her deep knowledge of Islam, though her search for her birth mother also plays an important part in her psychological journey.

Ghilzai and Portman’s script is witty and touching, full of moments that made the audience laugh and cry. I found it refreshing to see Muslim women on stage in all their complexity, with varying degrees of religiosity and spirituality. The lack of representation around Islam and concerning Muslim women more broadly in the American theatre has often made playwrights and theatres feel like the Muslim characters they put on stage had to be perfect in order not to reify misconceptions and stereotypes that Western audiences may carry with them. Many of the family’s arguments about Islam capture the layered and often conflicting ways Muslim women relate to faith, ritual, and identity.

SOSAN: I didn’t like the Mullah.

NADIA: Because he pointed out how bad you were at reciting the Quran–

SOSAN: I’m sorry that I wasn’t the Mullah’s pet, like you, wrapping myself in shrouds of fabric.

MARYAM: Khala Almas was not thrilled about the Hijab, that’s for sure.

NADIA: See what I mean Fatima, they look down on us for our devotion.

NOOR: No one is looking down on anything. It’s just we Afghans didn’t wear this Hijab stuff. Your mother and I wore mini-skirts and knee-high boots in Kabul.

SOSAN: I saw some of these pictures. You were very sexy, Khala Noor.

NOOR: Speaking of clothes, maybe next time you can wear the longer tunic. We’re in Saudi Arabia, not a fashion show.

Noor’s simultaneous concern with women’s appearances in Saudi Arabia, nostalgia for the mini-skirted Kabul of her youth, and confusion over her niece’s and Fatima’s decision to wear the hijab together illuminate how religion is shaped by geography, politics, and generational memory. Each woman’s relationship to Islam is mediated by where and how she has lived it—through migration, war, or assimilation. Maryam’s YouTube-learned prayers and her comparison of namaz, or five daily prayers, to meditation suggest a diasporic, globalized Islam in tension with Nadia’s orthodoxy, while Fatima’s conversion frames belief as chosen rather than inherited. Ghilzai and Portman’s script portrays Islam as a lived, negotiated journey—an ongoing pilgrimage through sincerity, confusion, pride, and guilt—and a breath of fresh air on the stage.

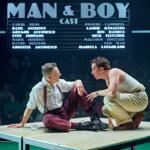

Afghan American immigrant Noor (Nora el Samahy, right) and her best friend Fatima (Jeunée Simon) in the world premiere of Pilgrimage by Humaira Ghilzai and Bridgette Dutta Portman, produced by Golden Thread Productions and Z Space and directed by Michelle Talgarow. Photo by David Allen Studio.

Having directed the 2024 staged reading of Pilgrimage, I was eager to see how this fully realized production would embody the play’s physical journey. Talgrow’s staging beautifully captures the play’s shifting geography, from San Francisco International Airport to the holy cities of Medina and Mecca, while maintaining a sense of fluidity and motion. The play took place in the round, with Mikiko Uesugi’s scenic design creating a flexible space onto which the world of the play could unfold. Apart from the seven gold pillars that extended from the floor to the ceiling, wheeled benches served as the primary scenic element, transforming the space seamlessly from airport gates to hotel rooms to sacred spaces. The movement of the benches, combined with Ray Oppenheimer’s lighting and Ard’s sound design, evokes both travel and spiritual passage. The result is a dynamic visual language that mirrors the women’s evolving relationships and inner transformations.

One of the production’s most powerful moments occurs when Noor becomes separated from the group during tawaf, the ritual circling of the Kaaba in a counterclockwise motion. The scene, rendered as a dreamlike blur of light and motion, transforms ritual into metaphor. As Noor chants “Allahu Akbar” in rhythm with the moving crowd, her family’s desperate search becomes increasingly physical. The disorientation of the pilgrimage mirrors their emotional fragmentation, while the act of circling, endless and rhythmic, embodies faith’s capacity for renewal. Oppenheimer’s lighting heightens this tension, evoking both the searing Saudi sun and the possibility of transcendence. Following the performance that I watched, I was told that there had been a scenic malfunction, where the Kaaba did not descend for the family’s first view of the holy site. While I can imagine that it was magnificent in subsequent performances, the acting and directing were such that I did not feel it was missing in the moment. As an audience member, I felt like I was in the heat with them, experiencing my own disorientation, and experiencing the beauty of the Kaaba for the first time as well.

The ensemble work in Pilgrimage is exceptional—measured, intimate, and generous. Each actor contributes not only to her own arc but to the delicate rhythm of the group. Noor’s repeated line, “All prayers answered and sins forgiven,” captures the tension between her faith in God and the lived reality of the secret she had been holding for some time. Yet as she repeats it, the phrase becomes increasingly haunting, revealing her longing for absolution in a world where her pain and guilt threaten to overtake her. El Samahy, no stranger to acting with Golden Thread Productions, delivers a stunning performance that allows the audience to journey into Noor’s psyche. El Samahy brings a quiet authority to Noor, allowing vulnerability to flicker beneath composure. Fatemeh Mehraban’s Maryam is sharp and emotionally precise; her tension between worldly success and moral reckoning is rendered with nuance. Leda Rasooli’s Nadia pulses with sincerity and restrained fury, while Isabel Alamine’s Sosan balances wit and restlessness, capturing a woman caught between rebellion and belonging. Jeunée Simon’s Fatima is magnetic, her grounded physicality and subtle humor making her both anchor and mirror to the family. Together, the cast builds an unforced intimacy that gives weight to the play’s rituals and arguments alike; their silences are as eloquent as their words.

Simon’s portrayal of Fatima is striking in its strength and vulnerability. Her ihram costume, a two-piece garment traditionally used for umrah, was designed by Fatima Yahyaa, features keffiyeh-print sleeves, a subtle but powerful detail that signals both political clarity and her individuality. Knowledgeable about Islam, Fatima occupies the dual role of insider and outsider, at one point jokingly, and with love, commenting on Noor’s limited grasp of Black identity in the United States:

NOOR: I know, but we’re Afghans. We can fight our way through anything. You Blacks have had your share of fighting for things, too.

FATIMA: Our fight is still going on.

NOOR: Yes, yes. I know about Malcolm X and Martin Luther [King Jr.].

FATIMA: Then you are fully informed about the struggle.

Each woman gets something that they are looking for, even if it is not what they might have set out for. By the play’s end, Maryam abandons her corporate life in pursuit of spiritual integrity, Nadia makes it clear that she wants to see where things can go with Fatima as they explore what it means to be more than just friends, Sosan rediscovers her sense of purpose and connection to her family, and Noor heads home with the family’s wounds exposed but ready for healing. The women gather for a final photograph, a gesture of reunion and impermanence. As the lights fade, the image of these five women, bound by faith and kinship, becomes the production’s final prayer for reconciliation.

Pilgrimage is an ensemble work about faith, family, and diaspora, blending realism with the spiritual surreal. Its minimalist staging invites audiences to imagine pilgrimage not as a journey with a fixed destination, but as a shared, transformative space. Through humor, tenderness, and ritual, Ghilzai and Portman craft a story of Muslim women who are complex, flawed, and profoundly human. The production stands as a testament to Golden Thread’s commitment to transnational storytelling and artistic solidarity, a journey in itself, toward a theatre of connection and renewal.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.