Pesach or Passover is the most widely observed Jewish holiday and arguably the most joyful. Celebrated annually in the early spring, the eight-day feast commemorates the Israelites’ liberation from slavery in Egypt and their newfound freedom as a nation under the leadership of Moses. It was in this spirit that Warsaw’s Teatr 21 originally conceived their 2016 devised work Pesach to święto wolności (Passover Is A Celebration Of Freedom) in collaboration with POLIN The Museum of the History of Polish Jews and the Open Museum project, an annual month-long program that makes information about Jewish heritage available to people with a wide variety of sensory and mobility impairments.

Teatr 21 has been participating in Open Museum since 2011 and has risen to international prominence as an inclusive theatre group that stages politically-charged social theatre in Poland and abroad. Founded in 2005 following a series of educational workshops for students with autism and Down Syndrome, the group has grown into a semi-professional company under the direction of Justyna Sobczyk, head of theater pedagogy at the University of Warsaw’s Institute of Polish Culture, and now employs a permanent cast of 14 youths and adults with intellectual disabilities.

In their daily practice, Teatr 21 operates similarly to a joint stock company. In addition to the actor-activists, the company also employs a team of teachers, writers, activists, and allies (led by Sobczyk) that serves as a panel of co-authors and dramaturgs to help the actors collect and curate material relevant to their lives and assemble them into fully staged multi-media akcja performatywna or “performative actions.” In addition to stewardship of the company, the team conceives of itself as a resource for the actors, serving at turns as magnifying glass and megaphone for the messages of performers who communicate with varying degrees of verbal acuity. The company, headquartered at the Zbigniew Raszewski Theatre Institute in Warsaw, works collectively, uses no scripts, and considers all of their pieces to be in continual development.

Pesach: Creative Process

The 2016 Passover play at POLIN, however, was a completely new work devised over a two-month rehearsal period. The production centered on the poetic concept of the actor-activists leading participant-spectators through a joyful meditation on the Israelite’s journey across the Red Sea. According to production notes, the original aim was to stage a vast procession, with the actors serving as so many Moseses and conveying their charges through a reenactment of the Jews’ exodus from Egypt. It was a powerful site-specific concept, as the museum itself is constructed on the ruins of the former Warsaw ghetto where thousands of Jews died in battle, defending the lost lives of their compatriots who starved under the oppression of Nazi forces occupying Poland during WWII. In Hebrew, the word “Polin” means both “Poland” and the imperative “rest here.” In leading the participant-spectators out of the ghetto through “Polin,” the work folds the history of the Jews in Poland back in on itself, paying homage to the legend of the arrival of the first Jews to Poland in the tenth century BCE, where they encountered what they thought was a new promised land of tolerance and renewal after centuries of persecution.

The actors’ role as leaders and liberators in the program would likewise invert the patient/caregiver paradigm endemic to relationships that the disabled typically have with their friends, families, and medical providers. In their “celebration of freedom,” Teatr 21’s actor-activists sought to take control not only of the narrative of Passover, but to re-define their place in society as full citizens and establish a voice in the public sphere. The vision of utopia cultivated in the rehearsal room was soon ruptured, though, by an unexpected political spectacle unfolding in the media.

Socio-political context

In January 2016, Janusz Korwin-Mikke—a notorious Polish politician and member of the European Parliament best known for his crass public statements disparaging women, the poor, and the disabled—made inflammatory remarks during a college address that led to a televised debate with disability activist Piotr Pawłowski. [1] When confronted with the harmful nature of his words, however, Korwin-Mikke doubled-down on his hateful rhetoric; his remarks sparked a national firestorm that played out on television for weeks. Although he covered many topics ranging from integrated education to an embargo on broadcasting the Special Olympics on television, the most troubling aspects of Korwin-Mikke’s rant centered on the rights of people with intellectual disabilities to participate in the democratic process and further to express their interests in the public sphere. In the now infamous exchange, Korwin-Mikke said plainly that people with disabilities do not rise to the level of being fully human, much less equal citizens. Furthermore, according to his view, the individual interests and opinions of the disabled amount to little more than garbage and “the retard [debil] takes no offense for the simple reason that he is a retard and so cannot be offended.” [2]

The Korwin-Mikke/Pawłowski debate aired on April 15, 2016, just one week before the beginning of Passover and the premiere of Pesach to święto wolności. Outrage rippled through the company and the team of teachers, dramaturgs, and facilitators gathered at POLIN to discuss whether the performance should be modified to address the controversy. Some of their more radical ideas, such as locking the participant-spectators outside of the museum and forcing them to wait outside for 90 minutes while listening to Korwin-Mikke’s commentary on a large PA, were rejected because they were disrespectful to the Ghetto Heroes Monument. Others, such as building a montage of clips of xenophobic comments made by a variety of world leaders and influential persons (Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, Jarosław Kaczyński, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan) specifically about the refugee crisis were rejected on the grounds that they erased the specific concerns of the company’s actors and overemphasized those of the facilitators. The team was starkly divided over the inclusion of Korwin-Mikke’s remarks in the program at all, with at least one member refusing to “stage a performance the aim of which would be to exchange arguments with Korwin-Mikke.” In response, other team members pointed to the quotidian anti-semitism that was pervasive before WWII and the culpability of those who stood by in silence, noting that to ignore the politician’s comments would be to “let it happen over and over again.” Presumably, no consensus was reached because rather than alter the overall structure of the performance piece, the team instead decided to disrupt it and insert the entirety of the debate (political and theatrical) within the production itself. The resulting assemblage was a poignant and at times painful agglomeration of the company’s conversations on freedom, sovereignty, self-reliance, and public voice.

Pesach to święto wolności: the experience

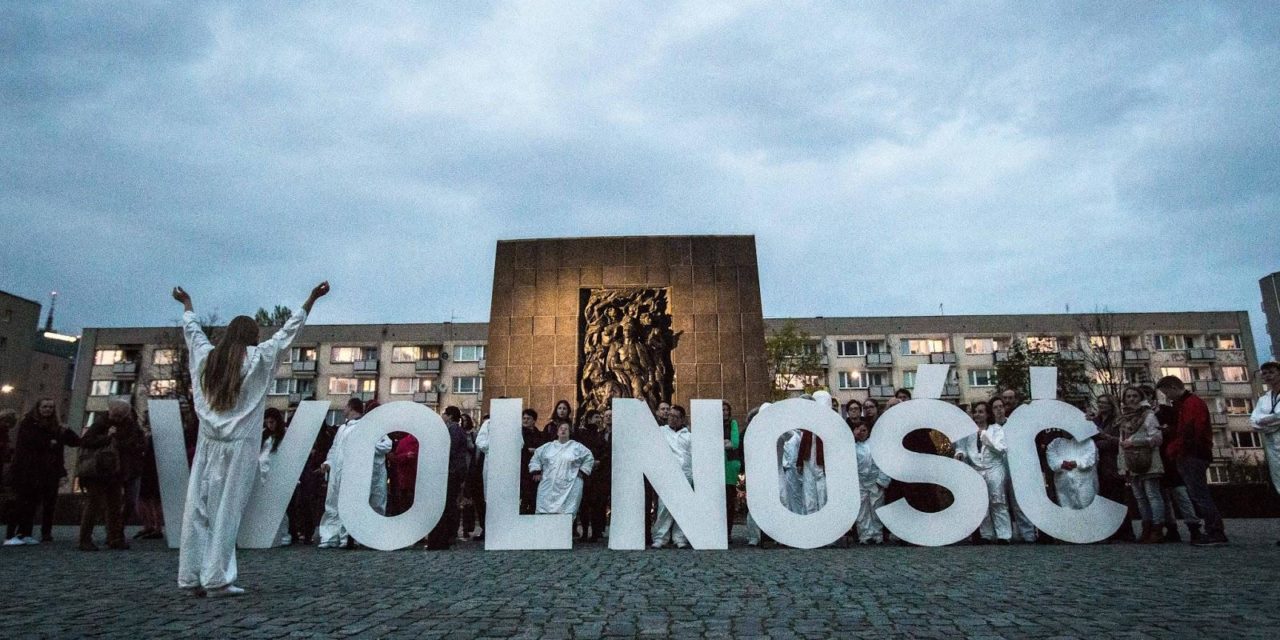

Upon arriving to see Teatr 21’s Pesach to święto wolności, participant-spectators entered POLIN’s grand lobby to the music of ocean waves and video projections of white-tailed deer prancing merrily in the surf. After some time, the actors entered from the courtyard in a disorganized parade carrying large wooden letters—some larger than the actors themselves—spelling out “wolność,” a heavily loaded Polish word that is typically translated as “freedom,” but also carries with it the connotations of liberty, sovereignty, and independence. “The Passover holiday ushers in a very difficult word—wolność, freedom,” Lipko-Konieczna noted. “As we are talking about freedom, we realized it is not a permanent state, it is not motionless. I think that freedom manifests itself in action, in a journey towards the given destination.” [3] In their quest to express this link, the team settled on dividing wolność into separate letters and having the actors carry them around the museum. The letters themselves were deliberately made of heavy plywood with no handles attached to make them cumbersome and “rather uncomfortable to carry,” thus communicating the notion that “freedom is a burden that we have to bear.” [4]

Gathering the crowd together, the actors next led a 15-minute meditation, with some encouraging participant-spectators to dance and sway like sea anemone while others read aloud the story of the exodus from Egypt. After some time, the participant-spectators were guided away from the sea and into the desert where they ventured forth into some of the “nooks and crannies” of the museum. Eventually, the actors led everyone into a narrow hall where a television was set to play. After the singing of the Passover prayers, the TV sprang to life and all witnessed Korwin-Mikke’s violent words together.

During this scene actors scattered around the room. Many writhed in discomfort and others plugged their ears. A few had retired with their letters to a glass-walled conference room down the hall to escape the experience entirely. As Korwin-Mikke faded out, the team of facilitators entered to read, in their own voices, the contents of their fierce email debate about the direction of the performance piece, the state of discrimination in the world, and the artistic direction of the company. They pulled no punches in their exchange and this theatrical debate went on long past the point where spectators in the hall became extremely uncomfortable. The correspondence was well-crafted and moving in its passion, but there was a keen awkwardness in contrasting the team’s eloquence and fire with the relative passivity of the actors in that moment, many of them in self-designed exile or actively covering their heads to avoid the worst of the conflict.

This segment of the performance was slow and tedious. The conflict, while real, induced anxiety in its refusal to be resolved. I remember wondering whether the scene unfolding might be approaching what Dani Snyder-Young calls the “theatre of good intentions.” [5] That is to say that the piece’s creators had a desire to promote real change, but the quorum of the facilitators had let itself become too self-reflexive and, in the process, overshadowed the actors and the spirit of the original production. There was a lingering question, however, whether the action was a well-executed attempt to produce in the participant-spectators the same feelings of helplessness felt by the actors themselves as they watched a national debate rage on over their individual fates while lacking the power and position to participate in it fully. Even amongst the allied relationships between the actors and the rest of the team, difference loomed largely and worked to make the system of exclusion ever more visible.

The third movement of Pesach, however, may have provided the first steps towards a productive conclusion. Following the debate, actors led the participant-spectators once again into the depths of the museum, this time reaching an auditorium where the entire stage was glowing blue. There the actors reassembled their wolność and took turns reciting all thirty articles of the United Nations Universal Declaration Of Human Rights. In spite of the segment’s simplicity, the emotion was palpable, as the team supported those who were unable to read or remember their assigned line to confidently and accurately speak it into the microphone. Assertions such as “Every person has the right to a free and fair education” and “Every person of age has the right to marry and start a family” take on an enhanced pathos with the dawning realization that these rights are not universal for those whose disability leaves them without personal autonomy and the legal protections of full personhood. The weight of these realizations was made further manifest, as the actors finished their recitations and invited the spectators up one by one with the request that they aid the actors in carrying all seven letters back up the three flights of stairs and out into the night. With this participatory dramaturgy, Teatr 21 not only generated in the participants the anxiety, fear, alienation, and disgust that accompany the experience of injustice but also enlisted the help of the now (hopefully) more receptive public in sharing the burden of their symbolic liberation. As the actor, Piotr Swend commented, “Freedom is independence. Freedom from all there is. Freedom is power. Freedom is a lot of work. … When I’m carrying a heavy letter around, I need people to help me. The more that people help, the easier it gets.” Lipko-Konieczna agreed: “It turns out that freedom is not an easy thing to accomplish; it requires sensitivity and the ability to think about one another.” [6] More than this, though, it seems to require space for disagreement and discomfort—it is this freedom to express one’s own opinion and interests that weakens not the political discourse, but the hegemonic grip on the categories of humanity.

[1] See “Korwin-Mikke nazywa chore dzieci bredzącymi debilami. Niepełnosprawni wzywają go do debaty.” In, Newsweek Polska (2016). Published electronically April 15, 2016.

[2] Integracja – Janusz Korwin-Mikke vs. Piotr Pawłowski. Edited by INTEGRACJA.tv, 1:00:30. YouTube, 2016.

[3] Teatr 21: Pesach – Making Of.

[4] Teatr 21: Pesach – Making Of.

[5] See Dani Snyder-Young, Theatre of Good Intentions: Challenges and Hopes for Theatre and Social Change, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

[6] Teatr 21: Pesach – Making Of.

References

Integracja – Janusz Korwin-Mikke vs. Piotr Pawłowski. Edited by INTEGRACJA.tv, 1:00:30. YouTube, 2016.

“Korwin-Mikke nazywa chore dzieci bredzącymi debilami. Niepełnosprawni wzywają go do debaty.” In, Newsweek Polska (2016). Published electronically April 15, 2016.

Snyder-Young, Dani. Theatre of Good Intentions: Challenges and Hopes for Theatre and Social Change. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. doi:10.1057/9781137293039_2.

Teatr 21: Pesach – Making Of. 10:00. YouTube, 2016.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sara Taylor.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.