Ruhollah J’afari’s Richard III Will Not Take Place is an excavation of real historical events. A Question of Madness is a work by Zhores A. Medvedev that addresses the ignorant Stalinists upon Russia’s October Revolution. Any resisting or complaining individual would be labeled as crazy, as sick in the head, or as having a mental disorder. In Medvedev’s book, which is also translated into Persian, Stalin is portrayed as the main puppeteer behind Russia’s intellectual movement and as someone who had authority in removing mass numbers of intellectuals from the scene in the 1930s and 1940s. The truth is that in Stalin’s era, the modern concept of psychoanalysis and even scientific inventions and discoveries about the human brain, nervous system, mind and soul all together found a new meaning, and psychiatric hospitals were rapidly filling up and being emptied to eventually eliminate intellectuals from Russian society. Along with his brother, Medvedev was detained in labor camps for a long time and kept himself away from the harsh work-related stigmas of Russia. The book A Question of Madness is one of the greatest and most revealing texts on Stalin, who obliterated art and replaced psychoanalysis, psychology, and catatonia with bewilderment, insanity, and craze, and imposed this reversed concept upon Russian intellectuals.

Ruhollah J’afari’s production is a modern approach to a more modern text. The text is about a great figure of theatre, Vsevolod Meyerhold, who struggled with Stalin’s restrictions, which aimed to separate him from his area of research on biomechanics for theatre and halted it from spreading to the world. It is necessary to note that although the text of this Romanian dramatist [Matei Vișniec] is modern, it is still considered an interpretation of “agitprop.”[1] With that said, Vișniec’s work, Richard III Will Not Take Place, embeds a commercial and propaganda nature.[2] Instead, Vișniec shifts away from the core of the Shakespearean play and aims to deliver an agitprop message, one that portrays Stalin and his demonic behaviors.

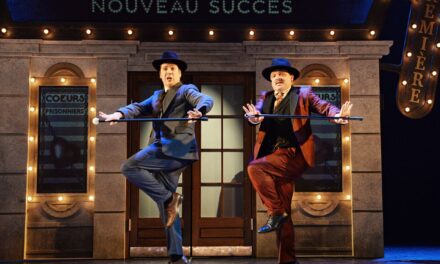

Mehdi Bejestāni. Photo by Fahimeh Hekmatandish.

J’afari’s performance is saturated with elements of youthfulness, freshness and a promised sense of modernism. We are fortunate to have such a stylistic, refreshing and contemporary director. Meyerhold’s pursuit of life is one of the main pillars of Russian theatre, and its reputation is put on the greatest world stages and honored by academics around the globe. Thus, such a performance is necessary and thought-provoking for [the Iranian] audience. In this work one views how psychiatric hospitals and illnesses are managed in Russian camps during Stalin’s time. Ultimately, the main goal of agitprop was to eliminate intellectuals and to create theatre that is short-lived and that cries out the name of Stalinist thoughts. Of course, Stalin is considered a type of a leader who, as one of our poets’ remarks, is like “A thief who approaches with a torch / selects better goods.”

Stalin was a first-rate linguist, literary man, and scholar who put all of this towards dark service and delusions, resulting in a society inflicted with schizophrenia, paranoia and other psychotic disorders. [One may ask], Mr. Stalin, in all honesty, ‘who is crazy?’ Is it Medvedev and Meyerhold or Sholokhov and Gorky’s ill fate? Another fact is that the October Revolution failed to deliver great figures such as Meyerhold, Gorky, Kozhikdar and Tsar’s Dostoevsky to Russia’s literary and theatrical community. Chekhov, Dostoyevsky, Gogol, and Pushkin are all great literary figures of the Tsar’s era, and the Russian revolutionary regime was not even close to producing another Raskolnikov.

The work of Ruhollah J’afari excavates these authentic historical events. He has produced this play with his expressive and energetic scenic design and his brilliant understanding of the Polish playwright’s text, a text that comes from a land with the most progressive and contemporary outlook on theatre. University students also cross boundaries with their work, as seen with groups such as STU.[3] With an enlightened mind, J’afari utilizes Meyerhold’s biomechanics and charmingly situates this important figure of theatre with his scenic design and the great and sometimes fabulous directed roles to portray the play’s provocative and promotional warnings. In my opinion, the performance of Richard in Vahdat Hall and the works of Vișniec in Chāhārsoo Hall complete a theatrical puzzle,[4] and how great is it that these works are presented in these warm and happy days in the heart of Tehran? I believe that J’afari’s clever selection has not only paid service to Meyerhold but has also made us witness Meyerhold’s biomechanics and biophysical techniques on the stage in Chāhārsoo Hall. In the words of Medvedev, “psychiatric hospitals”, or in the words of Heidegger, the “tents of psychiatry of our time”, and from Stalin’s era onwards, important topics such as artificial intelligence, bionic intelligence, cybernetics, holistic and system theory are topics that can be read in the early texts of our [the Iranian] revolution. Such topics are all considered brainwash subjects by Stalin, and thus, made a martyr out of such a great man as Meyerhold, who stood by and fought for his beliefs. This is one of the best reasons why J’afari’s trials and efforts have led him to success.

The fact that this great cast of Richard III Will Not Take Place selected a text from Polish theatre is a bitter examination of the state of our theatre in this day and time. The Polish bring the deepest and most prolific theatre performances on to the stage, and we will never forget the work of STU in Shiraz, which dramatically shifted our perceptions of theatre. Ruhollah J’afari’s work is in the same mold, and we do not want to neglect the great acting skills of the cast, such as Majid Rahmati, Hamid Rahimi, Nasim Shojaei, Pouria Soltanzadeh, Shahab Abbasian, Hesamoldin Mokhtari, Mehdi Bejastani, Mohammad Farajipur, Azar Kharazmi, Hamid Habibifar, Neda Haji Babaei, Reza Alavi and Kamyar Mohebbi, and especially the unique acting skills of Majid Rahmati, whose career as an actor has been full of dazzlement and success, from his hometown to Tehran.

Biography of the Artist and His Group Description By Farinaz Kavianifar

Rūhollah J’afari was born on January 13, 1980, in Tehran, Iran. He is an assistant professor at the Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch in Tehran, and a theatre director, dramaturg, journalist and researcher. He entered the world of art at a young age, commencing his secondary education at the Sedā and Simā Art School, which is operated under the Islamic Republic of Iranian Broadcasting (IRIB). He then earned a bachelor’s degree in acting, a master’s degree in directing and a doctoral degree in cultural planning and management from Tehran Azad University. He has authored the following books: The National Art Group: From Beginning to End, Culture, Theatre, and Leisure, and Research in the Cultural Resurgence of Theatre, and is the artistic director of the Guitī Theatre Group.

From right to left: Shahāb Abbāsiān, Hamid Rahimi and Hesāmoddin Mokhtāri. Photo by Fahimeh Hekmatandish.

J’afari’s first directorial experience was as a teenager in 1995, but it wasn’t until 2006 that he selected the official title for his team, Guitī Theatre Group. Guitī is a Persian word meaning cosmos, universe, and creation. This title was chosen reflectively, as the group strives to break geographic boundaries and limitations with art, specifically theatre, and aims to not only work on global texts but to also deliver a universal message to the audience. In 2006, the group worked on The Confessions of Perplexed Human Beings Who Crucified Their Christ for a Petty Price Due to Their Righteousness, which was written and directed by J’afari himself. After this production, Guitī focused primarily on Matei Vișniec’s (b. 1956) plays, beginning with Horses at the Window, in 2009; The Spectator Condemned to Death, in 2011; How Can I Be a Bird? in 2014, and Richard III Will Not Take Place, in 2018.

J’afari’s most recent production, Richard III Will Not Take Place, occurred at Chāhārsoo Theatre, in Tehran’s City Theatre, on July 22 through August 17, 2018. This play is an open adaptation of the Russian director Vsevolod Meyerhold’s (1874–1940) life and his inability to acquire a permit to perform Shakespeare’s Richard III under Stalin’s communist regime. The play emphasizes issues such as censorship and criticizes power and politics.

The article was translated from Persian by Farinaz Kavianifar.

About this performance and its director also read:

Theatre of Inquiry: Matei Vișniec’s Richard III Takes Place in Tehran

Russia Meets Iran: J’afari, Vișniec and Meyerhold, Partners of Ideology, Traversers of History

Notes

[1] Communist propaganda, especially in the form of art and literature.

[2] In Richard III Will Not Take Place, Vișniec encounters a perplexity and puzzlement in directing Shakespeare’s authentic version of Richard III.

[3] Teatr STU is a theatre group, first established in 1966 in Krakow, Poland, as a student-run organization for the local audience. Soon after, the group gained national and international acknowledgment and is now a full-time operating company ) Paul Allain, Gardzienice: Polish Theatre in Transition [Routledge, 2004](. STU had two performances in Shiraz, the first titled Fall, in 1973, and the other titled Polish Dream Narratives.

[4] The author is pointing out the close ties between Vișniec’s Richard III Will Not Take Place and Shakespeare’s play Richard III. He believes that an audience member who has the opportunity to watch both plays alongside each another will gain a better understanding of the atmosphere of Vișniec’s play.

This article was originally published in Persian at Honar Online, article #122540, August 18, 2018, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marjan Moosavi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.