Engaging with narratives that draw on the subject of male queerness can be precarious. Two major British productions seem to have proven this point within the past few years. Firstly, there’s Marianne Elliott’s staging of Mike Bartlett’s 2009 text Cock, which at the time of writing is running to packed auditoriums in London’s West End. Its protagonist, John, argues that “[g]ay, straight, words from the sixties made by our parents, sound so old, only invented to get rights, and we’ve got rights now”. He appears to reason that equality for gay men has been achieved. While this view isn’t shared by all characters within the play, it’s argued with convincing prominence. A similar sentiment is echoed in Matthew Lopez’s 2018 drama The Inheritence, which transferred from a run at the Young Vic to the West End and to Broadway. The protagonist, Eric, insists that with gay culture entering the mainstream there’s no longer a stigma attached to queerness: it’s becoming normalised and invisible. These beliefs are announced from prolific sites to vast numbers of spectators. But is this experience universal? While in large parts of what is broadly called the West, indisputable progress has been made with regards to LGBTQ+ rights, is that progress felt by all members of that community, regardless of age, gender, abledness, and social and ethnic backgrounds?

Sophie Swithinbank’s Bacon emerges against this backdrop. The play, which ran at the Finborough Theatre from 1 March until 2 April 2022, explores male queerness outside of the white middle class. In a production directed by Matthew Iliffe, mutual attraction connects two teenagers from single-parent households. Mark (Corey Montague-Sholay) is a new arrival in a Twickenham Catholic school; he’s timid, clever, eloquent, black, possibly neurodiverse. Darren’s (William Robinson) overconfidence comes across as overcompensating for his insecurity; he’s a white working-class miscreant with a penchant for subversion. Mark’s mother provides her son with a loving and caring middle-class home; however, the boy’s life is not without problems, as the dialogue hints at Mark’s self-harming tendencies. Darren’s father comes across as abusive and neglectful – his son is forced to skip meals. Upon realising this, Mark uses his pocket money to buy Darren lunch – a bacon sandwich, which lends the play its title.

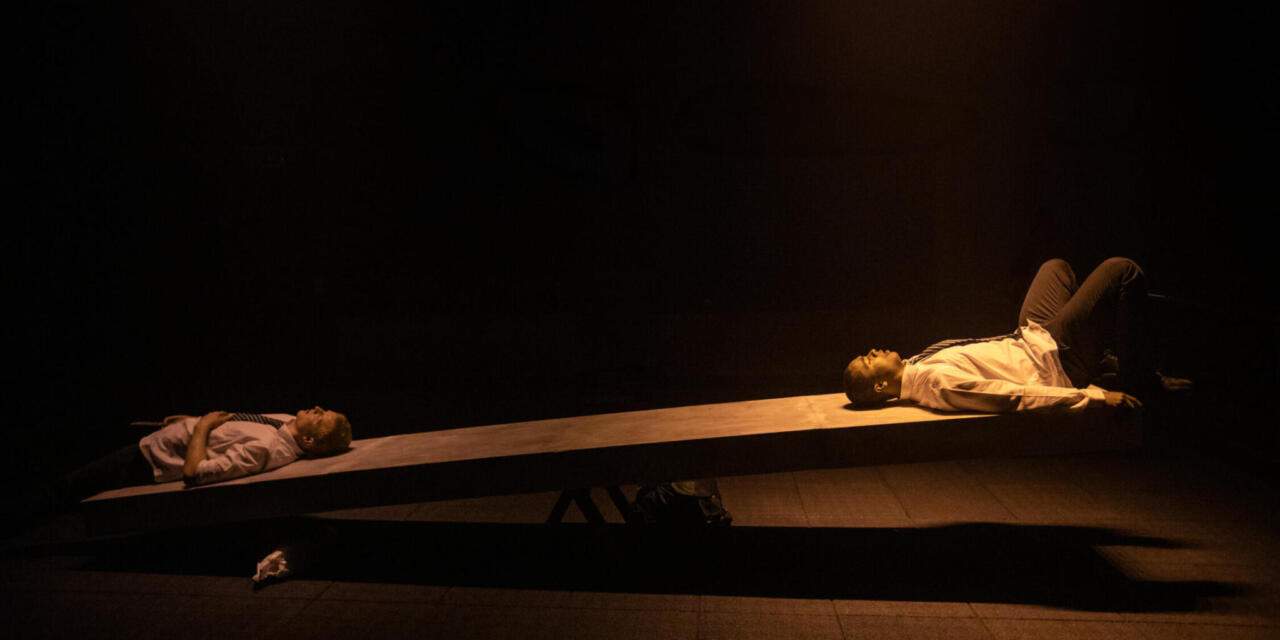

Mark’s gesture is an extension of the behaviours he was brought up with and that his mother impressed upon him. Likewise, Darren reacts to Mark’s gesture with what he knows of interactions with those closest to him – he expresses his feelings through harm and violence. This dynamic locks the boys in an uneasy power struggle. Their relationship is adeptly manifested through Natalie Johnson’s minimalist set, which places a large seesaw at the centre. In moments of tension, the play’s direction sees the characters lift and balance each other, accentuating the fluctuations of control, dissent, and submission. The actors turn the screw of an already tense atmosphere even further by directing gazes toward random audience members while delivering some of their lines. These simple but effective techniques result in a very palpable sense of danger that permeates the Finborough’s intimate auditorium. They place the production in the here and now, and do away with the conventional safety net that separates the audience from the world presented on stage. This is exacerbated by the stage being arranged as a catwalk, with the faces of other spectators discernible in the distance, making the experience of mental and physical violence unfolding as the play progresses all the more uneasy – violence that is witnessed, but not acted upon.

While acknowledging the presence of the audience, actors Montague-Sholay and Robinson never appear to break character, both delivering spine-shivering performances in their own way. Once Mark appears on stage, one of the first things he says is “You won’t want me to stop once I’ve started” – a bold statement that can all too easily overpromise. It doesn’t. The play’s shifting locations are evoked predominantly through descriptions delivered by Mark, and Montague-Sholay imbues said descriptions with an energy of someone for whom spaces can become overstimulating. As he races through his lines, he never lets the pace take away from their clarity. Robinson digs deep into his character to ensure he hits all the notes that differentiate Darren from a one-dimensional villain; he is a pressure-cooker of a person that blends a cheeky charisma, superficial bravado, repressed sexuality, and deeply rooted self-loathing. Both actors are tasked with occasionally transforming into secondary characters – and both do so seamlessly and playfully, making the production feel more densely populated than its two-hander formula would suggest.

Swithinbank’s writing is sharp and focused. Bacon’s intermittent structure shifts between a past and a present narrative. In ‘the now’ Mark, working behind the counter at a café, is confronted by Darren – five years since Darren inflicted trauma upon Mark. And in this confrontation, despite – or because of – the ordeal that Mark suffered, and the abundance of pain and the experience caused him, the playwright empowers him to set himself free, and finally begin to heal. The stage is set for Mark to say ‘no’ and be heard. And that ‘no’ – soft, quiet, painful – somehow resounds with a thousand echoes.

The play makes no claims to universality. Yet by focusing on a specific story of two individuals it extends its resonance much wider. It provides a platform to voices that remain stifled by the roar of much more prominent narratives – ones that peddle more comforting, but distorted realities. And in providing this platform, Bacon points to the blind spots and limitations of queer male stories championed by big-budget theatre. With reports of a tv adaptation on the way, there’s some reassurance that these blind spots are being noticed and that counter-narratives such as Bacon can extend their reach. But will Mark’s and Darren’s gazes send the same shivers down viewers’ spines from behind the safety of the screen? Although the Finborough run of the production has now ended, one can but hope its life will carry on beyond that. The problems raised by the play form part of a conversation that needs to continue within the realm of the theatre. And Swithinbank’s voice has some valuable insights to contribute.

William Robinson (Darren) and Corey Montague-Sholay (Mark) in Bacon by Sophie Swithinbank. Photo by Ali Wright.

Bacon

Written by Sophie Swithinbank

Directed by Matthew Iliffe

With Corey Montague-Sholay (Mark) and William Robinson (Darren)

Stage and Costume Design by Natalie Johnson

Lighting Design by Ryan Joseph Stafford

Sound Design by MWEN

Intimacy Direction by Jess Tucker Boyd

Finborough Theatre, London, 1 March – 2 April 2022

Seen on 20 March 2022

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Konrad Zielinski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.