We’ve been celebrating Shakespeare’s 450th birthday week with fun, festivals, exhibitions, a cake competition – and the launch of an improbably epic tour of Hamlet from the Globe in London “to every country in the world” and back.

On his 448th birthday, the playwright became the subject of the World Shakespeare Festival. It was at the heart of the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad and included the Globe to Globe Festival which ushered “37 plays in 37 languages” into Sam Wanamaker’s recreated Elizabethan playhouse.

This in turn, came only five years after the RSC’s Complete Works Festival staged all the plays at Stratford in one season – “the biggest international project in our history so far… with more than 30 visiting companies, 17 from overseas”. And we’ll go through this all over again in April 2016 when the Globe’s Hamlet returns from its great trek just in time to join in the lavish celebration of the poor man’s death.

It isn’t a coincidence that the RSC’s Complete Works season was a response to the greatest crisis of confidence in the company’s history. It is also not coincidental that the Cultural Olympiad’s organizers seized on Shakespeare as a way of giving some sort of coherence to the “complete and utter shambles” of this embarrassingly amorphous national project.

For the British, Shakespeare is a weapon (or in modern parlance, muscular brand) of first and last resort. And corporate thinking everywhere rules that anything “uniquely” successful should be repeated as often as possible, on an increasingly global scale.

The risk in all this is that British cultural nationalism – complacent yet desperate – can obscure something very important: the astonishing pliability of Shakespeare’s plays and their usefulness as a medium for self-expression by directors, performers and audiences around the whole world.

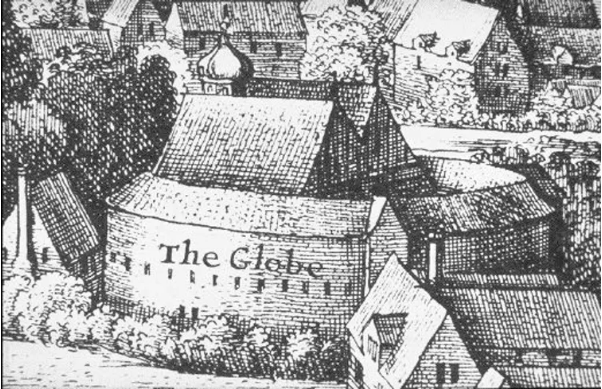

The Globe in 1647.

They were written in a period both of maritime expansion and internal religious tension when theatre became simultaneously a populist open-air entertainment and a candle-lit encounter for Court elites. And these plays, without exception, intertwine explorations of the self, kinship, the state and the spiritual. No wonder they travel well.

Forgive a few stories. During martial law in Poland, I was once taken away by two secret policemen (classically nice and nasty) to be interrogated: who did I know? After giving me a good fright they let put me on the plane, but they detained a large collection of BBC TV Shakespeare videos which their colleagues scanned diligently over the next few weeks for elements of subversion.

It would be unrealistic to claim that Shakespeare’s political analysis is so piercing that the Polish security service’s uncut screenings of Julius Caesar, The Comedy of Errors, and the rest contributed to the demoralization of the Jaruszelski regime and the collapse of European Communism. And yet, the thought isn’t totally fanciful. Shakespeare has a history of shedding new light on stale situations.

A decade later, on the brink of the worst fighting of the Balkan wars, liberal intellectuals organized a Shakespeare seminar in Belgrade. It was designed to coincide with the Presidential elections. As such, it created a rallying-space for anti-Milošević opposition figures and activists who took breaks from the demonstrations in the street outside to talk about Richard III and the dynamics of power in The Tempest.

The election was, of course, won by Milošević by a landslide, and the fighting escalated. Day and night we watched him play the lead in constant election broadcasts. They showed him walking messianically through devastated Serbian villages in a halo of light – an utter Richard III, posing as a pious churchman. Perhaps Shakespearean complexity will never match the twin powers of mass-media propaganda and election-rigging. But the power of recognition does work on those who see, study and perform these dramas around the world.

I have worked with Brazilian actors who recognized the 1993 Candelária massacre – the killing of street children by the Rio police – in the social cleansing in Measure for Measure.

And in Hamlet and Ophelia, Tokyo students told me they recognized stories that encouraged them to question, publicly, their families’ salary-man ethics and their fathers’ ambitions for them.

Probably anyone else sent abroad by the British Council could offer better examples. In many ways, it’s simply an example of low-level cultural diplomacy. But although the concept of “global Shakespeare” can be seen as a rump-colonial tool for sustaining British (and American) cultural influence, it’s a good moment to register that these plays have for centuries reconfigured themselves to match the concerns of the world’s cultures.

If we ask “Why Shakespeare?” – why have these particular texts been so popular, so insistently translated, so influential, so rich in codes – the answer has to be: “Who else?” Who else would have provided such a repertoire of ideas and passions if history had shipped different books across different empires?

“Shakespeare” (incorporating Fletcher, Middleton, Wilkins and all his other collaborators) demands to be revisited more than the great novelists – because by definition drama compresses ideas and gives them urgency. And these particular plays resonate more than, say, Marlowe’s (he’s 450 too) because Shakespeare was an actor writing for actors. His speeches leave them work to do, the lines are constructed to work through suggestion, implication and contradiction, by planting images in the imagination.

“Shakespeare” at home often means only what we need it to. “Global Shakespeare”, on the other hand, is a widespread process of empowerment.

Around the globe and back again. Pawel Libera

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on April 24, 2014, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tony Howard.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.