Goodman’s Resident Dramaturg on how her work gives texture and specificity to a production.

Consider the riddle of Neena Arndt’s work at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago. She conducts research that informs designs but doesn’t design sets or costumes or soundscapes. She often appears on Goodman stages but is not an actor. Arndt is a dramaturg who researches playwrights, characters and their lives, relevant social and political events, and other themes for use by actors, designers, directors, and sometimes press offices. She might even have a hand in refining a play adaptation. She is part of the community that builds a theatrical world.

As a member of the Goodman Theatre literary department for nine years (the past two as Resident Dramaturg), Arndt reads scripts being considered for production, prepares background materials for design and production personnel, refines script translations, and conducts public pre- and post-show events. In our recent conversation inspired by her work on Robert Falls’ adaptation and staging of The Enemy Of The People that ran from March 10 through April 15, 2018, Arndt describes the many dimensions of her role in staging in this timely story about public works and public corruption.

These days she focuses most on production dramaturgy and audience engagement through program notes, post-show discussions, and pre-show talks. Topics for pre-show talks are tweaked for each production, factoring in what she feels would be useful while not giving the whole plot away.

“I often give background information about the playwright, how the play came to be written, where the play sits in the playwright’s oeuvre, the production process and certain choices. But I avoid spoilers because I assume people don’t how the play ends. I’ll usually try to give a little nugget, a secret.”

She performed all these roles in the Goodman’s new adaptation of Eleanor Marx’s 1888 translation of Henrik Ibsen’s 1882 play The Enemy Of The People. In this new version, the roles of idealistic Doctor Stockman, his pregnant second wife Katherine, and his adult daughter Petra struggle with how best to serve their family and their community in the face of a water supply contamination that threatens the spa business that supports that town.

Lanise Antoine Shelley as Katherine and Rebecca Hurd as Petra. Photo: Liz Lauren.

Let’s talk about the 2017-2018 Goodman season of politically-tinged plays including Ivo van Hove’s staging of Arthur Miller’s A View From The Bridge about dock workers, Blind Date about Gorbachev and Reagan, The Wolves about a suburban girls soccer team, Father Comes Home From The Wars, and Stacy Keach as Hemingway. Literature and politics are strong in this season.

This is the first season chosen after the 2016 election, so it has a particular political flavor. That’s not to say that we don’t do political work in other years too. I would say the season goes there more explicitly than some seasons do. Many people say all art is political. I think I agree with that.

This production of The Enemy of the People is a new adaptation from a particular translation.

The translation is by Eleanor Marx, the daughter of Karl, who was a brilliant woman and a feminist figure. Her life is fascinating because she was a brilliant translator, brilliant academic, brilliant feminist who ended up killing herself at the age of 43 over a man, so it was a kind of un-feminist ending.

She was her father’s assistant, taking notes for him and helping him from the time she was 10 or 11 years old. We had the notion that Petra has served a similar function for her father. Her translation I would say is not particularly playable, but it is readable and clear and published a few years after Ibsen’s play was first staged.

Bob [Falls] is attracted to early translations that are done close to the time a play was written. He feels there’s something sort of pure or precise about them because that translator was living very close to the time the play was first done. Bob did an adaptation of The Seagull in 2010 that was also based on a very early translation by George Calderon.

Where did the new adaptation lead the production? You’ve mentioned the changes you’ve made in the female characters.

One of Bob’s big goals with this adaption was to bring the play into more contemporary parlance; the language feels like people talking. But what’s new has less to do with the production itself and more to do with the times in which we are living. In post-show discussions, one of the things that is landing with audiences is the contemporary relevance of the issues in this 1882 play. The language has been updated for us, but the ideas are Ibsen’s.

In this adaptation, the two women, Stockman’s wife Katherine and his daughter Petra, have been fleshed out and given more agency. Ibsen wrote some fantastic female characters such as Nora and Hedda, but not in this play.

Katherine is now a second wife pregnant with their first child. There’s a future generation to worry about; whatever Thomas chooses, there are going to be serious ramifications for his child. Petra is an adult daughter, a school teacher, with a bit of a stepmother-stepdaughter dynamic with Katherine.

Whenever I look at any historical period, I ask: what’s the role of women in that society? How do women work? What sort of access to education do they have? What are the expectations regarding age to marry or be considered an old maid? What expectations are there around having sex, and children, and child-rearing?

What is new and different about the world of this production?

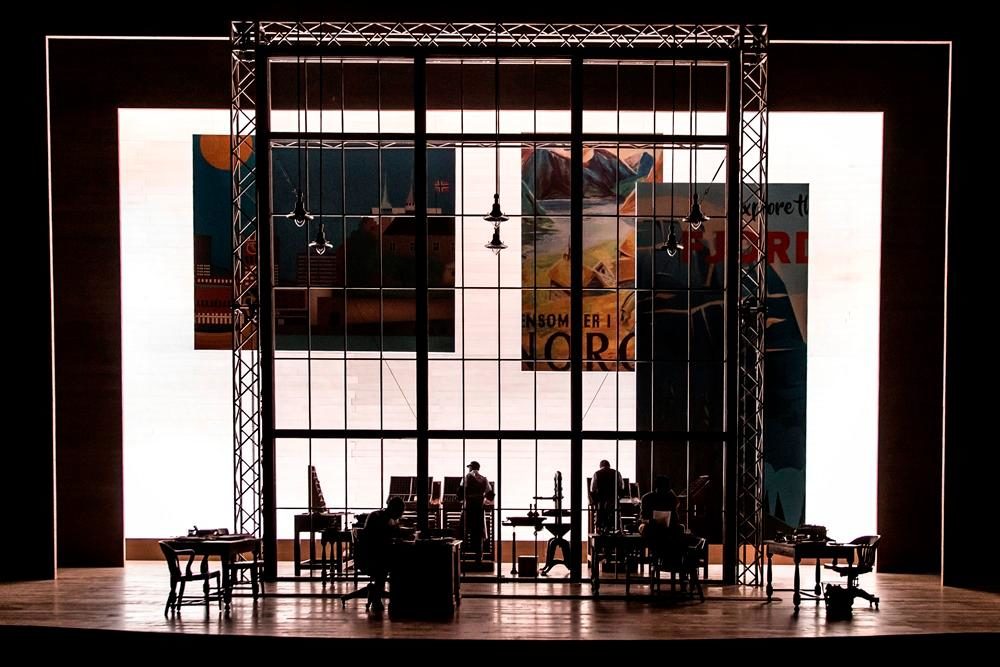

Bob likes my research to ground everybody in the time and place that the play was written or takes place. The play takes place in Norway in 1882 so I did research about that time and place so that everyone became steeped in that world.

There’s a timelessness in the production itself and the design choices. Some of the costumes and furniture have a definite 19th-century air, but there are also pieces from the 20th century–a t-shirt or a modern lamp. Ibsen is the “father of realism” but I wouldn’t say that there is an attempt in this production to re-create an exact slice of life from a particular place and time. The play is set in Norway, sort of in the 19th century, but those boundaries are purposefully blurry.

What do you love most about dramaturgical work?

I always enjoy diving into a world, whatever that world is. It’s different every time.

In this play, I asked a series of question. What does it mean to be a journalist at this time? You can think you know what a journalist is, but do you, in terms of that exact time and place? Petra is a young woman who is a school teacher. What does that mean? Peter is the mayor of this small town. What does that mean? Thomas is a doctor, which was a very different thing than it is today–less education required to do it, in part because there was less knowledge to be had. Germ theory at the time of this play was new; it was only a decade or so before this play was written that they started to sterilize surgical instruments on a regular basis.

I enjoy tailoring my research to a process, coming in every day and seeing what’s relevant, helping everybody understand the play and the world better. It’s giving texture and specificity to the production that it wouldn’t otherwise have.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Martha Steketee.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.