An assemblage of intriguing aesthetic strategies, what Mallory Catlett’s This Was The End lacks in structure it makes up for in auratic power. Using Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya as a pretext, Catlett and her crack team of designers and technicians have turned Mabou Mines’ new space into a staging ground for an unusual memory play featuring authentic living and inanimate pieces of downtown performance history.

The set is a wall salvaged from the old PS 122 building. Bearing a “Smoking Permitted” sign that succinctly conjures another era, it is a piece of architecture that has borne witness to countless hours of artistic experimentation. To be in its presence alone is to find oneself encountering a multitude of ghosts. The newly renovated building is almost unsettlingly pristine, but by restoring this artifact to its site of origin, Catlett foregrounds in our awareness the many triumphs and false starts, breakthroughs, and breakups that must have occurred against this particular backdrop. Indeed, the first “scene” of This Was The End takes place without any actors at all. The wall—history itself?—is the only character. The house lights come down and we become aware that a perfect, life-size photograph of the wall is being projected onto the actual wall. Practically indistinguishable from one another at first, the difference between the image and the reality grows as the projection begins to pulse and vibrate, to list to one side, then the other, take on new textures, contract and expand as an electronic soundtrack builds in intensity. Recorded memory, this impressive feat of technological choreography suggests, is mutable, subject to infinite varieties of manipulation.

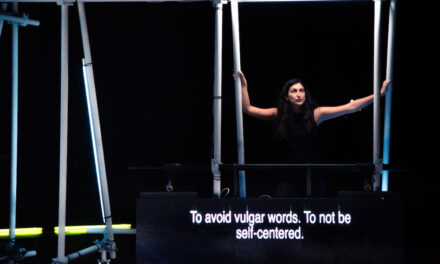

Presently, we are joined by a cast of vintage performers that includes Black-Eyed Susan, a founding member of Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company, and Paul Zimet, Artistic Director of The Talking Band. They, too, comprise a precious compendium of theater history, and their unstable powers of recollection are the poignant subject of This Was The End. Assisted by audio cassette recordings of their own voices reciting lines of dialogue or summarizing scenes, the aged actors embark upon an approximation of an approximation of Uncle Vanya. Their rendering of Chekhov’s play is complicated by the fact that they don’t really know their lines. They are also sharing the space with projected video of themselves. The most dramatically fraught interactions, therefore, are between individual performers and their own audiovisual avatars. Rather than asking us to become invested in tracking the vectors of desire between characters, the production emphasizes the relationship between multiple temporal iterations of each individual performer.

This is highly fertile ground that might have been more assiduously cultivated. The performers’ attitudes towards their recorded voices are not consistent, which occasionally muddies the conceptual clarity of the piece. As Astrov, Jim Himelsbach appears to rely on the recording as a mnemonic aid, letting it prompt him as he delivers his lines, while Rae C. Wright as Yelena seems content to allow her recorded voice to do most of the talking for her. As Sonya, Black-Eyed Susan ekes out an engaging presentness that renders her more independent of the crush of technology surrounding her than the others. As Vanya, Zimet seems to relish getting into little tussles (or jam sessions) with the audio apparatus, which is being manipulated live by onstage sound artist G. Lucas Crane. But the production is a little too in love with the delightfulness of its own technological possibilities, and the dramaturgy gets buried. The performers, accomplished as they are, get trampled by the tech.

When we come to Act Four, the lights abruptly come up bright, projections disappear, and the performers are left to finish the play without the crutch of the audio recording. Without the technology enfolding them, they seem perilously vulnerable and exposed. The simple pathos of an older actress alone and struggling to remember her line is heightened by its contrast with the media oversaturation that precedes it.

While Catlett might have built This Was The End around most any dramatic text and still accomplished her aims, certain lines from Uncle Vanya prove particularly resonant in this context. “My sun has set” is repeated again and again, casting a shroud over the spectacle of these septuagenarian performers playing roles written for much younger people. Also significant is Astrov’s eerily prophetic speech about human folly in the face of climate change, which expands our focus from local things that have met or will meet their demise (individual performers, the East Village as it was, the avant-garde) to global extinction.

Ultimately, though, This Was The End is not so much an elegy as an unsentimental assertion of continuity and persistence. In fact, no sentiment seems to capture the production’s ethos so well as Olga’s final speech from Three Sisters.

“Time will pass on,” she says, “and we shall depart forever, we shall be forgotten; they will forget our faces, voices, and even how many there were of us, but our sufferings will turn into joy for those who live after us…it seems that in a little while we shall know why we are living, why we are suffering….If we could only know, if we could only know!”

This Was The End affirms the questioning, striving, and, yes, suffering that has always been the common lot of artists. While individual traces may be erased, the spirit of this collective quest will survive until the end.

This Was the End

Created and Directed by Mallory Catlett

Text from Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya

June 7-June 16, 2018

Mabou Mines Theater

New York City

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jessica Rizzo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.