Undine is a three-act animated opera composed by Stefanie Janssen and Michaël Brijs. The pandemic transformed the originally staged production into a digital format, which bought about new possibilities to the operatic medium. This innovative endeavor recalls Brian Staufenbiel’s graphic novel opera Everest (2021) and L.A. Opera’s shadow puppet animation of Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex (2021), which were both conceived during pandemic circumstances.

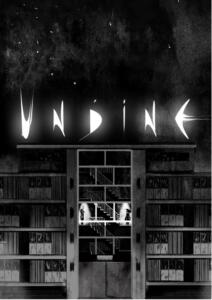

“Undine” poster. Photo credit: Undine team.

Undine revolves around a mermaid whose addiction to plastic disrupts the lives of Rodmenia, the unhappy wife of a tailor, and her neighbor, Anselmo, an eccentric philosopher. The composers drew on an expressive range of styles, from classical music, pop music, to electronic music, which lends a boundary-blurring ethos to the opera. Premiered in 2021, the opera has enjoyed global screening in many parts of Europe including the Netherlands, UK, Estonia, Greece, Belgium, Spain, Germany, before arriving at New York’s PROTOTYPE 2023 festival.

Before having watched the opera, I can’t help but be reminded of Ravel’s “Ondine” from Gaspard de la nuit (1908), which was based on a poem about a water nymph seducing an observer through her singing, to visit her water kingdom. It was considered to be one of the most notoriously demanding pieces a pianist can ever encounter. Thus, I was curious what the opera would portend.

Unsurprisingly, Undine is inspired by multiple authors’ shared fascination with the mermaid figure. In the summer of 2018, singer and performer Stefanie Janssen read the book Stil de tijd (“Time on Our Side”) by Dutch writer and philosopher Joke J. Hermsen. She was struck by Hermsen’s discussion of Ingeborg Bachmann’s novel Malina (1971), about Undine. Hermsen writes,

It is a story that’s both a declaration of love for human beings and an accusation against them. She writes that hidden within each of us there is an Undine, a mermaid, which, however invisible and unnameable, responds to our urge to break the fetters of conscious identity and the age in which we live. Only when we open ourselves up and dare to take the risk of our certainties collapsing can we breathe freely and gain new insights.

Treating Undine as an entity straddling between human and animal, Janssen comes up with an animated opera that makes space for the fantastical in humans. What would we do when we are offered an escape from the humdrum of our life? Will we be truly liberated? Or will we—yet again—give in to new obsessions, and lose ourselves along the way?

Act II. Rodmenia and Undine. Photo Credit: Undine team.

The creative team wrestles with these questions in the abstract, poetic animations created by animators, and the eclectic musical landscape. Each act has its own distinctive soundscape and animator, blending into a cohesive whole.

Less concerned with a naturalistic presentation, the medium of animation favors the evocative. Composed in black-and-white tones, the opera forces us to channel our attention to the visual flow on screen, and the psychology of the characters. Voices that spring forth are not attached to any bodies, but operate non-diegetically.

A new audiovisual language is born. We observe two media streams—the visual and the acoustic—co-existing alongside each other, gesturing towards the poetic.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jingyi Zhang.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.