Sonne, los jetzt!, Elfriede Jelinek’s new theater piece, is imperative with an unknown addressee. Is it the Sun or humanity that needs to make a change? Obviously, this is a first of many rhetorical questions, and rhetoric has been a central feature for Jelinek ever since. Also, how could we even blame? Could we seriously expect a change in behavior or acting from “the”—which is to say —“our” Sun? Now that humans are accustomed to thinking of the Anthropocene as the era in which their impact has started to change the Earth’s ecosystems on planetary scales, Jelinek’s genius change of perspective lies in giving agency and subjecthood precisely to the most innocent star above us. The sun-as-subject gazes upon us, finally to disregard us, but also to reflect, instead of us, on what global warming might ultimately mean for other animals and us. As a reversion of the metaphoricity of illumination, the Sun enlightens what human reason was unable to see. The play, therefore, repeats in a mantra-like form of alliteration, the Sun is “the light that indicates” (zeigt), “shows herself” (zeigt sich) and “creates” (zeugt).

The Austrian Nobel Prize winner upholds a linguistic ferocity with words carefully threaded into a stylistic stream of consciousness, uttered by the Sun as a monologuist. The world premiere of the play at the Zurich Schauspielhaus, directed by her long-term collaborator Nicolas Stemann, offers stagecraft excellence for the dark jocularity of the piece.

Jelinek’s reversed heliotropism virtuously recapitulates and unpacks our time as a field of floatings discourses around a general ecology with different entry points, but with profoundly limited ways of exit and only half-hearted, desultory solutions. The trembling voice in the lament of Greta Thunberg, the indifference of an interrupted lecture on climate justice, random fragments of eco-activism, hilarious ramblings of conspiracy theory, familiar doomerism and remnants of classical eschatology are all remixed in ever-new attempts to sort out what is really meant by being constantly said and what could be thought anew if we refrain from dogma and cliche. Jelinek’s piece is also a kaleidoscope of philosophies of time and times that have started to end.

Preceding a provocative prologue, the very beginning of the second part opens with a jolting echoed statement, “It is too late”. First uttered and whispered as choking gossip that spreads like wildfire among the people, the repetition transforms into a question and goes on to be negotiated. After realizing that “It is too late” might be a truth, a communal choir, holding hands, chants the phrase like a choral, inviting the audience to join in. For only what, if not to calm and secure ourselves in a joyful and humorous sense of community? But this is one of the many traps and abysses of the piece. In fact, Jelinek never leaves us on secure ground with what is enunciated or could be taken as a statement, a position, a prophecy or an idea of hope or despair. And the piece’s strength is in not offering an ending. There is always another turn, another twist. There is always more hope than we could have hoped for, or a darker dystopia to what might be a realistic future. It is furthermore difficult to attribute statements to subjects, since all common beholders of such subjecthood (politicians, activists, scientists, tourists etc.) are substituted by the rather odd and unheard subject of the Sun. In Die Vollzähligkeit der Sterne, Hans Blumenberg once called the moon “the last placeholder of Anthropocentrism”. The Sun, though, is too far and alien from being compared to us. There is no “man on the sun” to paraphrase the R.E.M. song. The Sun is a radical distant non-human figure and force. In Plato and Goethe, of course, the human eye was thought of as “sun-like”, created cosmologically by the Sun, but the same is not valid in reverse. The flowers offer their beauty to the Sun, but their sacrifice is unconsidered. The Sun burns in Jelinek’s piece until all the religions of flowers come to a terminus.

The Sun is not human-like, even though it raises life, and might have been personified by mythologies and religions. In this sense, Jelinek’s sun-as-subject can also only halfway be compared to its staging in the “theatrum mundi”. In Calderón’s plays, the Sun is part of a world viewed from below. In Jelinek`s play, it is the reversed perspective. The Sun is our star, but just that.

One moment in her piece is very insightful for this change of paradigm, when the Sun refuses, in an empiricist agnostic manner, the existence of the monotheistic god. “I have no god, and I also know no god”. Here, perhaps, one of Jelinek’s early major themes persists in the harsh criticism of the monotheistic god and the catholic patriarchy (of course, back then, mainly with a view on women in Austrian society). Feminism, which was so central in her work, is somewhat abated. Nevertheless, it persists, if only in caricatures, parodies, resentment, and conspiracy mansplaining.

However, considering that the Sun is conspicuously female reassures us that Jelinek still addresses burning feminist issues as they intersect with other concerns, such as the devastating effects of climate change. This seemingly understated connection begs the question: Is the Sun’s exasperation also shared by women who have, in several ways, been disparaged, demonized and side-lined? The following lines seem to allude to this inference.

Her own woman. I reject death, I am the life by way of killing, and I give myself, I spend myself, I overspend myself. I am by going all out, I make myself the sacrifice and I also make sacrifice, I, Goddess of Radiance, I devote myself to myself. No other woman is worthy to fall, although now they also take me. No woman is worthy to fall, although now they also take women for that, for the sacrifice, they are now also permitted to fall, albeit on another field. On a rock, which I can’t wear down.

Karin Pfammatter. Photo: ©Philip Frowein

The field of discourse is presented by Jelinek as a colossal language game. Wittgenstein is quoted- but needs, as the pun has it, to be sung for it to be adequately understood. “Can you imagine being endlessly dead?” Jelinek’s Sun empties untenable provocations into rhythmic language, poetic if one may, with a flood of onomatopoeic words with multiple associations featuring Phoebus Apollo, Lucretius and many more.

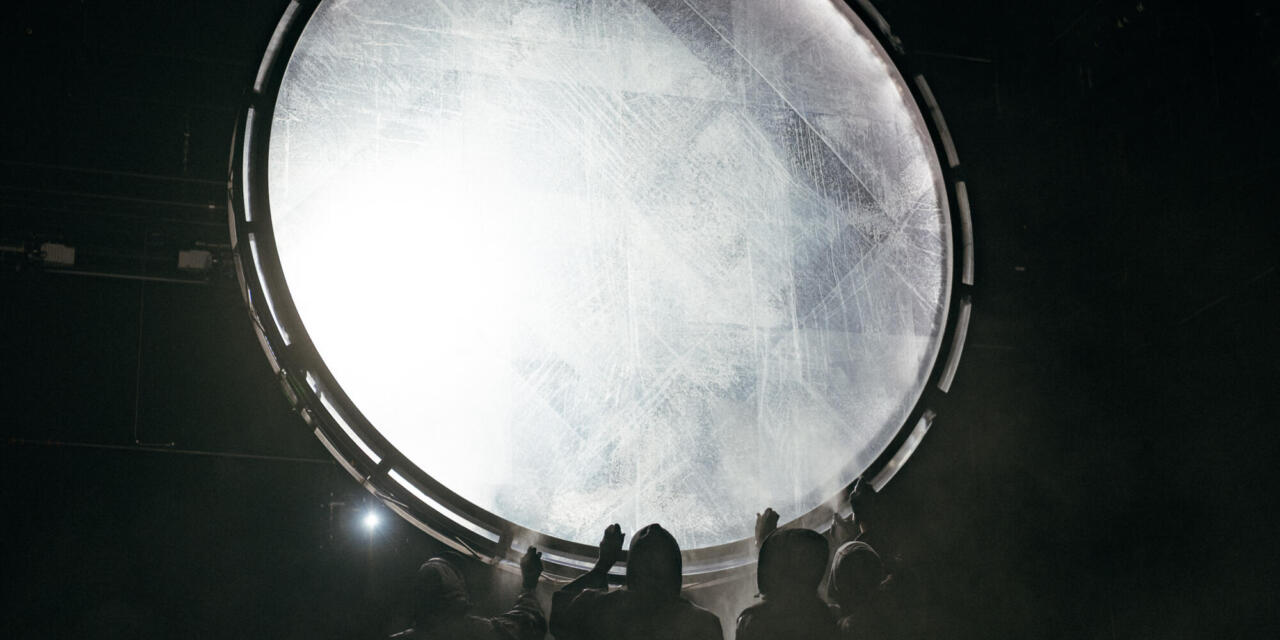

Nicolas Stemann transforms this monologue into a polyphony of voices, sometimes talking in unison or over each other, beneath a silver-covered celestial form, whose foiling thaws away very ungraciously.

With a series of subtle religious, scientific, mythical, and philosophical allusions, Jelinek offers us a cornucopia of varied yet convincing scenarios. The oldest of them might be that of the world-in-flames, the “Ekpyrosis” from Ancient Greek “conflagration”, by which the Stoic philosophers imagined the destruction of the cosmos by a great fire.

Now, what to do them!

At the play’s end, a few camp-like fires burn, and masked people stand in the background as they bow and disappear into the darkness. Yet, a strange creature crawling across the stage lingers: an oversized tardigrade defying even the most catastrophic environmental conditions. And before everything blacks out, Tom O’Bedlam’s rendition of the last lines of TS Elliot’s “The Hollow Men” ring through, enigmatic, dream-like, with a distressing calmness and a nearly re-enchanting change of accentuation:

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

Sonne, los jetzt!

By Elfriede Jelinek

World premiere

Theater: Schauspielhaus Zurich

Director: Nicolas Stemann,

Stage design: Katrin Nottrodt,

Costume design: Katrin Wolfermann, Music: Thomas Kürstner, Sebastian Vogel, Video: Johanna Bajohr,

lighting: Basil von Breitenbach,

Dramaturgy: Bendix Fesefeldt.

With: Alicia Aumüller, Daniel Lommatzsch, Karin Pfammatter, Sebastian Rudolph, Lena Schwarz, Patrycia Ziólkowska.

Premiere on December 15, 2022

Duration: 2 hours 20 minutes, no intermission

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Toni Hildebrandt and Zainabu Jallo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.