The Sheen Center is, I find myself thinking, the perfect place to host Locus29’s Hell Dialogues. Its underground stage is framed by angular steel walkways, audience lighting dulled, the air cool from the walk down. Punctuated with backlighting in an otherworldly purple, it is easy for one to feel descended into a chill flame, an impeccable emotional backdrop for the marriage of Sartre and Plato the audience is to witness.

Anna Zinenko in Locus29’s Hell Dialogues. PC: Kate Baranovskaya

Sartre’s Huis Clos [No Exit] and Plato’s Dialogues may not seem the most obvious of combinations, parallels found only—initially—in the word “philosophy.” Expressing their connection is a task adapter Dan Veksler took on with admirable vigor: guided by Masha Kotlova’s direction, the sister scripts are interwoven with a surrealist existentialism that would do Sartre proud. From the actors’ first moment of entry, done in twitchy silence, to the final brash dance party, one is enveloped in an unapologetic absurdity.

Hell Dialogues finds its grounding in Sartre’s Valet, played by Leo Grinberg with sinister luminescence. This iteration places the Valet in a far more vocal role than the original’s Charon-like usher; together with his Uncle, the Socratic head valet, he becomes debate personified, physicalizing the dichotomy of what it means to be human in conversations of tyranny and justice.

All this while Garcin (Max Katz), Estelle (Kylee Jacoby), and Inez (Anna Zinenko) scrabble in their own personal Hell, No Exit to offer reprieve from their triad tortures.

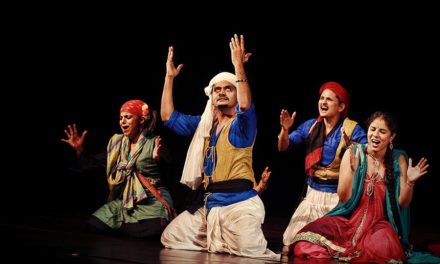

If this sounds rather chaotic, that’s because it is. Freneticism largely lends itself well to production; leaned into, it crafts a feeling of arrythmia, the insanity that is being a walking contradiction, human. Kotlova’s psycho-physical approach to direction makes this chaos integral: Garcin’s hands spasm, he folds in on himself and chokes in a snarl; Inez tears at her clothes, trying to breathe, breathe, breathe, sitting as a toddler entertaining herself; Estelle moves as Edwardian fairy, feinting and fainting in equal measure. The Valet and his Uncle (Peter Murphy) do calisthenics on the side, calling reminders of “There is no God in Hell.” Together, they make quite the interpretive quintet. One must applaud the commitment of the actors.

Kylee Jacoby and Max Katz in Locus29’s Hell Dialogues. PC: Kate Baranovskaya

It paid off in several key moments. Katz as Garcin gave a stunning performance of his final moments on the physical plane: spotlight on, his tied hands writhed, mouth contorting, a gasping incantation of fear and necessity. Jacoby and Zinenko provided with a beautiful dance, trading places, trading partners with Estelle’s Faceless Man; a waltz both staccato and languid in alternation, the two exuded grief and guilt and love and lack of apology, all. It was enough to tear empathy for these Hell-bound monsters onstage.

There were times, however, that this persistent freneticism hindered the reception. With bombardment of movement, the mind struggles to pay attention; it needs a balance of quiet to shock it back to consciousness, something that Hell Dialogues is missing a bit of. When physicality lessens, the chaos continues with Plato’s debates: Uncle and Valet parry and riposte on what exactly humankind is. Their debate is quick-witted and quicker-paced, enough so that the audience is left reeling. There is some intentionality in that dizziness, I’ve no doubt, but the production would benefit from providing its audience with reprieve to ensure they’re with the cast. A further integration of the two scripts would assist, as well. There are loose threads connecting the two; still, they feel like two separate performances ground together.

That said, Hell Dialogues boasts an incredibly strong ensemble cast. Its utilization of music—written by Marc Ribot, The Tiger Lilies, and Beliy Ostrog—is near-perfect. It provides excellent query, my favorite of which being “What is a tyrant?” Its set design, by Anna Kiraly, is a compelling mixture of pop art, IKEA furniture, and thermonuclear coloring. Overall, even at its weakest points, the production had me. It was a delightful evening of philosophy and oddity.

To learn more about Hell Dialogues, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.