The ace director has often faced flak from traditionalists.

For well over a decade now, Deepan Sivaraman, an associate professor at the School of Culture and Creative Expressions in Ambedkar University, New Delhi, has been questioning notions of stage and text, both as writer-director and as curator of theatre festivals. In his quest to highlight a new theatre language that is primarily visual rather than verbal, Sivaraman has faced flak from traditionalists. In this interview, Sivaraman talks about what it means to lead the charge of the avant-garde. Excerpts:

Indian theatre has metamorphosed over the last five years. Spare, abstract, polemical and visual. Why has it taken this leap?

I don’t see it as a leap at all. Manipuri director Lokendra Arambam’s Macbeth – Stage of Blood, set on a lake, was produced as early as 1997. Yes, scenography may have gotten primacy in the last 5-10 years due to continuity in practice by a few directors, which includes me, who started to explore non-text-centric, spatially interactive theatre after 2005.

At the time, Arambam’s adaptation of Macbeth was considered a rare experiment, but now a production like Khasakkinte Ithihasam [directed by Sivaraman], which has a non-linear storyline and is a prime example of the language of scenography, is accepted as an established form that audiences can intellectually and emotionally engage with.

It’s true that Indian audiences are more familiar with text-based proscenium drama, but in the last decade, we’ve had some productions that have proposed a new theatre language that is a hybrid of physical, sensorial and spatially poetic art form and not just a vehicle for literature. Directors like Anamika Haksar, Anuradha Kapur, Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry, and Abhilash Pillai have consistently worked towards this change.

What is this visual language? As the traditionalists say, the story takes a backseat. Can one call it style over substance?

Theatre is a visual language. I would like to call it the Theatre of Scenography. It challenges the supremacy of text in theatre. Conventionally, we understood the written script as key to the play-making process. Therefore, traditionally, the playwright was always supreme. Of course, good literary work offers the poetry of speech in theatre, but theatre is not just about spoken words and how the actors deliver it against a painted backdrop.

Good theatre, for me, offers physical poetry, which includes the poetry of sound (literature) along with bodily presence, visual metaphors and a sensorial experience. But all these elements will only produce meaning when we place the audience in such a way that they can intellectually, emotionally and physically engage with the performance. This spatial configuration between performer and spectator is key to understanding scenography. Scenography is not merely the decoration of space; it’s about meaning-making, making poetry in space and time. It has a long history in Europe, very much linked to the avant-garde. Our inability to read the language of visual poetry leads us to think that the visual has no substance. Theatre in India has not been as orientated towards the avant-garde as visual art, cinema or literature has.

Avant-garde theatre director Deepan Sivaraman.

At a seminar in the National School of Drama earlier this year, some stalwarts said traditional theatre was sacred and, therefore, unchangeable. That it faced certain death if this ‘global trend’ was allowed to take over. Your comments?

Modern Indian theatre, established during the late 18th century, was deeply influenced by Western theatre. But Indian theatre has a much longer history, and it offered physical, spatial and ritualistic experiences. The Ramlila of Ramnagar, Koodiyattam, Theyyam, Kathakali — they are all physical and visual experiences. Theatre is not an extension of literary art; it’s an independent art form.

The intercultural theatre of Grotowski, Barba, Brook, and Schechner can be discussed here, but perhaps it makes more sense to discuss Kavalam, Thiyam and Karanth’s ‘theatre of roots’ movement. They explored a new visual language as early as the late 60s. In the 70s, Ebrahim Alkazi directed some spectacular open-air productions like Andha Yug and Tughlaq. Thiyam’s Uttar Priyadarshi is another fine example of scenography.

The director is all-powerful in traditional theatre, whereas the new language envisages collaborative work between artists, technicians, and director. Is that why there is resistance from the old guard?

In conventional play-making, the only meaningful collaboration happens between writer and director. All other artists, including actors, are often downplayed. The director is presented as the guru, the reservoir of all knowledge. It is a welcome sign that we have now started to consider the actor as an intellectual person and not just a trained body with a good voice. In my theatre-making, I prefer to have the entire team collaborating from the very beginning.

But traditionalists say the new language marginalizes actors, making them just another prop, whereas actors are supreme in realistic theatre.

For me, a theatre is a hybrid form, an amalgamation of various artistic elements. I am not keen on any theatre that places these elements in a particular hierarchical order. I believe that good actors are vital for the success of a production, but I also believe that a good lighting designer, music composer, set designer, dramaturge and sound designer are equally important.

Some of the most powerful performances by actors I’ve seen in recent years are Nale Wali Ladki directed by Anuradha Kapur, and Neelam’s Bitter Fruit and Naked Voices, both excellent examples of hybridity.

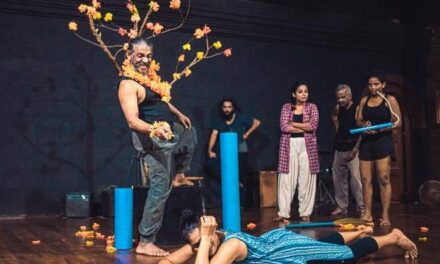

A scene from Sivaraman’s Dark Things.

Intimate performance spaces have emerged; small, box-like; people’s lawns, homes. Are prosceniums being rejected?

As society has changed substantially, so has our relationship with the world. Technology is integral to us now. It has become even more important that we engage with and assess everything we encounter in new ways and be wary of what we are offered as ‘the truth’. So, conventional theatre, which allowed us to look through an open wall, is no longer able to answer, question or provoke the changed sensibilities of our times. That’s the reason it’s being rejected around the world. We are now more attracted to what we see and experience physically rather than what we hear. The new theatre is responding to this change.

What do you see as the future of theatre in India given these emerging trends?

Since the time of the Greeks, the theatre has been primarily about words. Even today, we often equate the success of a play with its script. How can we begin to look at new and hybrid forms of performance that want to break down the hegemony of the word and lead us to different, deeper and more provocative experiences? The answers are contentious, but the question is becoming increasingly urgent.

Do you think existing scholarship in India is equipped to read this change in theatre language?

I think it has to catch up. I am not familiar with a single book published in India in the last two decades that discusses the works of theatre directors who have brought in the new visual language. The reason we are having this debate is precisely because our scholarship has failed to articulate the change. For them, the spatial set-up of a play like Virasat is a disturbance in watching it, or the raised metal hammer in Dark Things is an excess object to satisfy the director’s ego. I think the reason for this ignorance is laziness and reluctance to read about the new theatre, as also the lack of experience in watching theatre. Our theatre certainly needs informed scholarship, which can critically read new works with a historical and theoretical understanding.

Many veterans were considered radical in their own time. Why are they not embracing change now?

This is a question only the veterans can answer. I am quite happy with the idea that one day I will be thrown into the dustbin of history by a younger generation of theatre-makers. I am sure that 20 years down the line, the theatre we call avant-garde today will be old-fashioned and probably redundant.

The interviewer is a senior journalist, writer and theatre practitioner.

This article was originally posted in The Hindu and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sohaila Kapur.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.