Peesappilly Rajeevan talks about his artistic journey, the state of Kathakali today and what needs to be done to make the art form strike a chord with contemporary viewers.

It will be too simplistic to describe Peesappilly Rajeevan as just a busy Kathakali actor. He has tried to re-imagine characters and roles and is equally adept at doing male and female roles, be it a structurally robust Ravanolbhavam or an emotion-packed Nalacharitham or Karnashapadham. His imagination comes alive in dramatizing poetry in solo acts. Witty and articulate, 55-year-old Rajeevan has made his lecture-demonstrations on Kathakali entertaining and comprehensible to the uninitiated. The sixth standard boy who was fascinated with Kathakali after watching Kalamandalam Gopi asaan as Nala has come a long way. Excerpts from an interview with FridayReview:

What sparked your interest in Kathakali?

As a child, I used to watch a lot of Kathakali performances and was fascinated by it. The trigger was watching Gopi asaan as Nala at Peringode one day. I told him that I wanted to join Kalamandalam and learn Kathakali. He said that I would have to ask my parents since joining Kalamandalam would mean giving up formal education, something my mother didn’t approve of. My relative, Cheruvally Raman Namboothiri alias Appuettan, was a Kathakali artiste. I moved to his house and joined a school there in class seven. I stayed with him learning Kathakali until I graduated in economics. To become eligible for the cultural talent scholarship I had to move to an institution. So I joined PSV Natyasangham and trained under Kottakkal Krishnankutty Nair asaan for two years.

Why did you decide to go to a drama school after Kathakali training?

I think I inherited some interest in contemporary theatre from my father. I joined the School of Drama in Thrissur to hone my talent. But the atmosphere there was not to my liking. I didn’t get to do the projects I wanted and so left after three semesters.

So after that, you decided to become a professional Kathakali actor?

Professional? I would call this a passion. Appuettan used to say that art is not for art’s sake; neither is it to make a living. It’s an aesthetic enjoyment. If your objective is to make money, you will be disappointed. But at the same time, you need money to exist. There is an in-between space — that’s what art is all about. To me what’s more important is a role that you love to perform, an audience that I value and an ambiance that is positive.

How were the early days?

In the 1990s there were no stages for young artistes as you have today. We had no chance to do major roles. Even artistes with 15 or 20 years of experience ended up doing small roles. We could manage only three or four major roles in a year, such as Arjuna in Santhanagopalam or Bheema in Kalyanasougandhikam. As for other substantive roles, we couldn’t even dream about getting a shot. It was a frustrating period. In 1995 I was called to a professional drama troupe on contract. I had to go whenever the troupe had a program and hence started losing out on Kathakali. But it wasn’t easy to give up the stage especially after I received the best actor award from the Kerala government in 2003. The turning point was when the Kunju Nair Trust in Karalmanna [in Palakkad district] organized a workshop in 2006 for 10 “most promising” youngsters. That was a confidence-booster; the realization that there are people who consider me in the frontline of Kathakali, as a serious artist and one with the potential to grow. That was when I decided that Kathakali would be my field. By then the Kathakali scene had also started to change. More stages were coming. It was no more a temple festival ritual. Youngsters started getting good roles. Then came along social media that gave a lot of exposure to artistes. I could ride that trend.

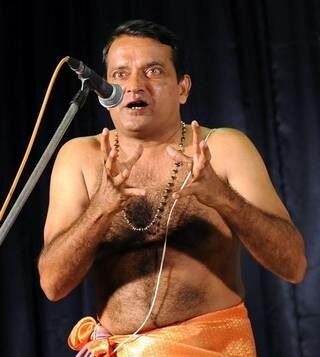

Lecture demonstration by Peesappilly Rajeev. Photo Credit: K Pichumani.

Is exposure to modern drama a help or hindrance to your traditional theatre acting?

I found it positive and beneficial — modern drama gave me new perspectives and Kathakali gave me the energy. I would say that contemporary drama gets its energy from the traditional theatre. Drama professionals today are looking to Koodiyattam and Kathakali. Both are theatre after all.

You are known in Kathakali circles for new interpretations. For example, the role of Asaari in Bakavadham. Any other character you think needs re-imagining?

Many people appreciated my treatment of Asaari. I have done it only twice. I couldn’t fathom why that character had to be a comic. He had a mission in Mahabharata — to save the Pandavas from the house of lac. Asaari has all the requisites of a serious character such as a structured entry, and iratti, ida kalasam, vattam vacha kalasam etc. But all these nritta elements were executed ludicrously. So I took this serious approach —I didn’t change the structure of this role, but only took out the comical element. Another character I would love to interpret anew is Brihannala in Utharaswayamvaram. I must muster the courage to do that. All the other Pandavas entering Virata’s palace incognito have a new name and a new costume. But Arjuna as Brihannala gets the same pacha character’s costume, albeit with breasts. The treatment he gets is that of a male character; even his verses project ‘veera rasam’ that befits a hero. I believe the transperson factor has not been fully addressed.

Kathakali is perhaps the only theatre where the green room is a public space. Your thoughts on that?

Crowded aniyara is a disturbance, even a nuisance. But no one wants to speak out. Painting the face requires focus and undivided attention. This is also the time when we think about the characters that we are going to portray. I believe the aniyara must be a private space. I like the arrangements at the venues overseas — those interested can watch or take photographs from a distance behind a barricade. What the real lovers of Kathakali should do is to stay back for 10 minutes after the program and share their experience of that performance with the artistes who will welcome honest feedback. This will help the artiste and the spectator.

How do you have any system to mentally prepare for a role?

I try to be by myself to focus on the character; a withdrawal into oneself. That’s all one can do in these circumstances. We are not machines that can get in and out of roles with a switching mechanism. I believe Kathakali artistes have a few things to learn from Koodiyattam. Watching Nangiarkoothu has helped me immensely. The technique Nangiarkoothu artistes employ to become one with the character and draw audiences’ focus on them can help Kathakali artistes doing female roles or highly stylized ‘pacha’ (heroic) characters. Kathakali should learn this from Koodiyattam. This will also make the acting experience a very pleasant one.

You have popularised lecture demonstrations with your wit and wisdom…

I felt that the seriousness with which we artistes approach our roles was not apparent to the audience. So I started out with children in the school where I work. Unlike adults, they have no qualms about asking questions. To familiarise them with the various aspects of Kathakali such as abhinaya techniques, mudras, and kalasams, I adopted a language and an idiom that the students will understand easily. But later I found that grown-ups too found it enjoyable. For example, in Thrissur Kathakali Club we did a familiarisation class for 22 days where some 60 people regularly attended. I believe this has had a very positive impact on the quality of enjoyment and appreciation of Kathakali.

What’s the state of Kathakali today?

This is a very good time for Kathakali. The youngsters are more knowledgeable, more observant, and aware of and exposed to other art forms. They evaluate their own performances and judge their peers and seniors. They don’t respect you merely for being their asaan. You have to command their respect with your performances and by setting examples. There are several such youngsters today. They think about characters, they are receptive to changes. These are good pointers. But we also need to make Kathakali more broad-based and egalitarian. There are pockets that still remain an upper-caste preserve. There are people, mainly in the organizational front, who find it comforting that this remains their sole preserve. We need to consciously interfere to break this elitism. For example, when Kunnamkulam Kathakali Club was launched, many of the viewers had no exposure to Kathakali. Now they have started thinking about the aesthetics of this art form. They even bring their own fresh insights. Such spaces exist not just in Kunnamkulam, but in every village and town. We need to go back to school. There are lessons in school syllabi that offer a window to Kathakali and we should explore how this can be opened up further to spark serious interest in the students. But most of the time the teachers are either not equipped, or they do not have the time to take it forward. There was a ‘Noorarangu’ (100 stages) program done by Kalamandalam that was very effective in taking Kathakali to new groups of viewers. But it wasn’t followed up. I notice people are taking the effort to learn the rudiments of Kathakali with workshops and mudra classes. All in all, this is a good era for Kathakali. Institutions like Kalamandalam can do more with projects such as ‘Noorarangu’.

This article was originally posted at The Hindu and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Achuthan T K.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.