Nalini Malani has won the prestigious Joan Miró Prize for 2019, and she talks of her journey.

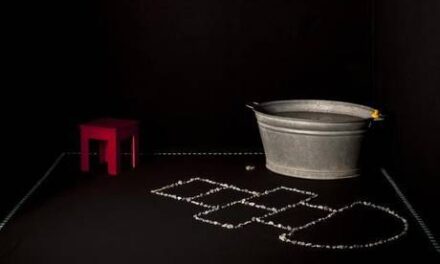

One of our most thought-provoking contemporary artists, Nalini Malani, known for her lush, politically charged mixed-media paintings and drawings, videos, installations, and theatre, was recently awarded the prestigious Joan Miró Prize for 2019. Malani’s works give voice to the silenced, particularly women. The award covers the production of a solo exhibition scheduled for 2020 at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona. Excerpts from an interview:

Congratulations on the Joan Miró Prize. What does this award mean to you at this point in your career?

This is my fourth international award in the last seven years, but this one feels quite special. So far the Joan Miró Prize was given to high-profile Western artists like Olafur Eliasson, Pipilotti Rist, Mona Hatoum, and Roni Horn. This is the first time that it is given to a non-Western artist. Therefore this acknowledgment is, I think, not only important for me but for Indian art, and non-Western art in general.

You have described yourself as a fan of Miró’s work. How has his work influenced you?

In my last year of studies in Paris in 1972, I met Miró at his solo exhibition at Galerie Maeght. I had seen reproductions of his works before but to see them, in reality, was a life-changing experience. Miró worked in contrapuntal layers (where lines are independent but relate harmonically to each other).

These superimpositions made me realize the idea of simultaneously using different subjects within one artwork or different moments in a narrative. It inspired me and over the years I developed a lexicon of simultaneities that became a crucial part of my own artistic language as can be experienced even today in my current all-encompassing video/shadow plays.

The previous recipients of this award are all known for their avant-garde works in multi-disciplinary fields. Have you been as influenced by their work as by Miro’s?

I have seen the works of most of the Miró Prize winners over the last two decades. I do admire their work but would not say they had any direct influence on my art. For them to experiment with different artistic formats within the Western art scene must have been a given.

When I experimented beyond the painted frame in the late 80s, it was akin to suicide. I had two daughters to bring up and educate and my new works, like ephemeral wall drawings, artist books, video and theatre plays did not contribute to my sales, nor was there appreciation from the Indian art scene. It was the changing social fabric and suppression of the voiceless, especially women, that drove me to find new forms.

Your art career has always been spread between India and the world. Does this globalization reflect in your paintings as well, since your work is also about uprootedness?

The subjects I deal with in my art have not been restricted to India but embedded in our global cultures. This is possibly one of the reasons why exhibiting internationally came so naturally, even before one spoke about globalization. Uprootedness is not always negative, as it also comes with the affirmative possibilities of experiencing linkages. This helps to find a new place and meaning, as well as responsibilities that should come along with the process of globalization.

You once said that an individual can take responsibility for the collective. In terms of India and the world’s rise of fundamentalism, how would you see this happening now?

Maybe it should not be ‘can’ but ‘should’. Especially when the changes imply a change in a direction that would, in the long run, harm the collective and the individual. The collective does not include only the majority. Fundamentalism leads to narrow mindedness. It leaves no place for an inclusive society and leads to the destruction of the essence of life.

Nalini Malani

Artsy is calling this the year that older women replace younger men as the art world’s darlings. Do you see this happening in Indian art as well?

I would say that this change of interest already started in 2012 with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev as the artistic director of Documenta (13) in Kassel, Germany. In India, except for the exotic bourgeois painter Amrita Sher-Gil, the importance of the senior female artist was acknowledged only in the last decade. This recognition in India has a lot to do with the pioneering role of Roobina Karode at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. I do hope this current acceptance of the female artist in India and abroad, old or young, is a long-term shift. Suppression by the alpha male not only in the arts but also in other disciplines has lasted too long and brought the world to the brink of collapse.

How does an artist in India get this kind of recognition, which it took even someone with your acknowledged talent so long to achieve?

The process of international recognition took so long for my generation, as the West simply showed no interest in the art of the rest of the world until the 90s. My important breakthrough in the West came about just after the turn of the century with the acquisitions of video/shadow plays by the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 2001, and the MoMA in New York in 2004. And, of course, most importantly my first solo exhibition at an international museum was at New Museum in New York in 2002, curated by Dan Cameron.

It might be hard to imagine, but there was at that time no interest at all to report on or review this international solo exhibition within India, neither in the newspapers nor even in art magazines like Art India. This process of international recognition has, of course, completely changed in the last decades, as we can already see with Amar Kanwar, Raqs Media Collective, and Sheela Gowda, to name just a few.

The writer, the author of a fantasy series, specializes in art and culture of South East Asia.

This article was originally posted in The Hindu and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ritika Kochhar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.