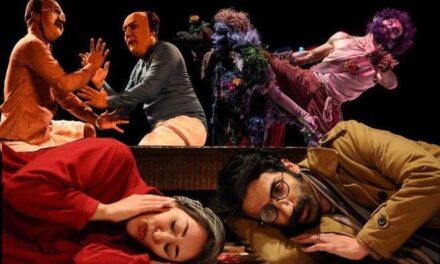

Acclaimed Iranian playwright Mohammad Yaghoubi was in Toronto directing the Canadian premiere of his play A Moment of Silence as part of this year’s Summerworks Festival. Yaghoubi is a well-known face in Tehran, where his plays have won numerous awards and usually play for forty-night runs. Here in Canada, though, he’s a newcomer to the scene.

I sat down with Yaghoubi to talk about the play, his directorial practice, Iranian politics, and what it means to stage this complicated work for Toronto audiences.

You have written over ten plays. Why did you choose A Moment of Silence for this festival?

The first reason is that it has the best translation of any of my plays. I noticed that from the feedback and responses of English readers. In its American staged reading, the audience was able to understand some of the witty nuances in the text. The second reason is that A Moment of Silence is my most acclaimed play, mostly because it has two parallel stories. On the one hand, there’s Shiva and the surrealistic aspects of her story, and on the other hand, the play shows the political turmoil in contemporary Iran. I took an experimental approach in writing this play particularly regarding using puns and figurative and idiomatic language.

Many consider A Moment of Silence one of the best plays in Iranian drama. To what extent do you think the play’s textual and verbal qualities are preserved in the English translation and how much is lost?

The most important part that is lost is the play’s puns and figurative language, and by this, I don’t mean archaic or literary language. I believe the contemporary language used by common Iranians can also be replete with word play, witticism, and irony. For instance, in a scene called “Urashima,” which is based on [the character] Sheida’s stream of consciousness, I play with the word Urashima and Shiva, and through this alliteration, I let the character move between reality and the abstract state of her mind. I am skeptical about whether the English translation can communicate what is going on at the level of word choice. Another example would be the idioms and expressions in the play but what matters for me is the way the translator has succeeded in giving the English reader the feeling that this play is more a play written in English than a translation of a Persian play. But what is preserved? I would say, A Moment of Silence has been admired for its distinctive dramatic structure, and this gives me the confidence to introduce myself with this play.

A Moment of Silence is an audacious reflection on the Chain Murders that happened in Iran from 1988 to 1998. It also recycles memories of the 1979 revolution and the Iran-Iraq War. It seems deeply contextualized in Iran’s local and temporal context, so the Iranian audience’s collective memory and shared history help them establish a strong connection with the play. Do you think the play will be able to create a connection with a Canadian audience?

Undoubtedly the play will resonate less for a Canadian audience, regarding both language and content. But it will change shape, and this is a quality of every artistic work. It transforms by encountering a new audience but it still contains its basic shape, and that’s what matters most. Seeing a Canadian audience understand it so well is very enjoyable to me. Iranian cinema has gained the self-confidence to attract world attention, and Iranian theatre needs to gain that self-confidence as well. The responses to the play that I have received have proven that regardless of its specific political content, it is raising universal issues about human relationships and experiences. Staging a play in a free country that criticizes an established order is not a defiant act but what matters most here is that A Moment of Silence is telling its story well enough to be understood by Canadians.

A Moment of Silence is a political play because it makes certain hidden issues visible. What are those issues?

The most political question it raises is: “Why should expression lead to death?” The play makes this lack of security and freedom [in Iran] visible. Moreover, it presents a family’s life and how they lose hope and happiness over the course of time. It shows how losing freedom of expression coincides with losing happiness and hope.

And how do these political questions relate to your aesthetic choices?

My dramatic aesthetics are very much dependent on literature. I aim for a literary quality in my theatre and try to find a way to make it performative on stage. For instance, there is a scene in which the playwright is writing a play about three sisters, and she is constantly receiving threating phone calls. She can neither answer the phone nor write, so we see the characters become motionless. They are waiting for the time when she can resume writing. This play is full of such tiny performative devices. In another scene, “A Piece of Music for Her,” there are three versions of one scene. Each time we see the characters from a different point of view. This could be described as a cinematic technique. Another example is the play’s ending when the audience is asked to stand up and take a moment of silence. This disturbs many familiar dramatic conventions.

Do you think a Canadian audience will accept this?

I’m curious to see the Canadian audience’s response when they’re asked to stand up and be silent. In Iran, we were asking the audience to be political activists by standing and being silent. The very act of standing was transgressive, but here I’m not sure standing can be interpreted as such.

What are the differences between the Toronto performance and the 2001 performance in Tehran? More precisely, what are the changes you’re making to the original production?

The biggest difference is the amount of time in production and pre-performance process. In Iran, we spend more than three months in rehearsal, and at Fadjr Theatre Festival, we had space at least 12 hours before the show. Here I had to prepare the show in 4 weeks, and at SummerWorks we have very little time in the theatre so choosing a minimal set design is no longer an aesthetic choice but an obligation! And there is the privilege of writing without censorship, which is motivating me to write more.

In Iran, you had the walls of the apartment close in to show the passage of time and the restrictions that put pressure on the characters’ living conditions. How are you doing this here?

Here I’m not using walls closing in. Instead, over the course of the play the white floor gets smaller to show how life becomes more restricted for the characters.

You have changed the gender of one of your key characters from male to female. Could you elaborate on why you made this choice?

In the Toronto production, the playwright is a woman. I believe choosing a woman as a dissident playwright is more applicable to the current reality of Iran and even of the world. Women’s rights are the most political issue these days. I should add that I have an obsession with changing my own work, so this change was a pleasant response to that urge.

What is the necessity of staging an Iranian play on the Canadian stage?

I believe in the vitality of performing art for uniting cultures. The fact that a group of Canadians is spending a month working and living with an Iranian text for performance is a fantastic opportunity. This could never happen when watching an Iranian film. Moreover, this event introduces Iran and Iranians to Canadians who may have acquired a distorted image about them from the media. And lastly, performing A Moment of Silence introduces theatre audiences and artists in Canada to what’s happening in contemporary Iranian theatre.

In Iran you are known for the creative strategies you have devised to circumvent censorship, for instance, you’ve used the term ‘25’ to replace the swearing words that have sexual overtones. In another production, one of these techniques was having your actors and actresses wear head covers (the very scarves commonly used by Iranian women). Could you explain more about such strategies?

Heart of a Dog was a dramatic adaptation of a novel by the same name written by Russian Mikhail Bulgakov. The 2015 production was the revival of this play. My intention in deciding men to wear headscarf came from my response to the image of a woman that the Islamic state has had disseminated in recent decades. As in the case of ’25,’ I thought this strategy is helpful to ridicule censorial regulations. Choosing headscarf for male cast gave me two opportunities: first, I could satirize the mandatory dress code established by the Islamic government, second, it made me able to highlight the fact that the Soviet Union like Iran was controlled under a similar despotic regime. Although communism is against religion, the fact that they had their people wear exact, similar outfits made it comparable to an Islamic state. In Iran also the state dictates Islamic sartorial codes for women. Not all the male cast supported this idea, and some first avoided wearing hijab. But then they accepted to do that.

And how was the authorities’ reaction?

Our performance was to run for thirty nights, but when the state censors saw men wearing a headscarf, on the eighth night, they warned us that the performance would be banned, particularly because we surprised them. In the run, through we did for them to get the license of public performance, men did not have hijab. After several negotiations, I decided to have the cast remove their scarves to save the show but even for eight days, it was an audacious way to ridicule mandatory veiling, and I’m very content about what I did.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marjan Moosavi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.