In recent times in India, we have seen the actor’s presence eclipsed by technology in productions affiliated with national institutions. The actor is reduced to a scenographic tool and converted into a component in a show. Upon closer examination, this can be seen as a case study of neoliberal imagery celebrated by the State and its Institutions. My paper questions the notion of acting processes and methods that create performers to fit into these new shows. Can this be called an acting method? What leads the National School of Drama to make this genre of show at their annual student fair? How do methods and pedagogy of actor’s training become intertwined with technological devices? Is it related only to the final presentation, or is it inherent in the process that is then canonized and emulated by a number of acting institutions in India? I study these vital questions via the work of one of the leading directors of contemporary Indian theatre, and a faculty member of NSD, Abhilash Pillai. Every year he directs a student production featuring a profusion of technology on and off stage, performed publically amidst great publicity. How does technology affect a young actor’s training, and construct the imaginative as the final outcome? Through Pillai’s case, I shall also explore the evolution of an “Indian acting training process” that started with the inception of the drama school in 1956 and its need to respond to tradition and “roots.” Does this create a “body-based acting method,” or is it inevitable in its own historical conception? How does a “rooted” body adjust to what I would like to see as its “transformation”?

In the past two decades in India, theater productions organized and funded by the State through the National School of Drama (NSD), have blended text, acting, and technology in a spectacular manner. These productions have come to utilize theater techniques that were earlier not deemed suitable for a State institution to work with. In what follows, I shall elaborate on the transformation of contemporary Indian theater toward a spectacle and a neo-liberal imagery that was first rejected and then celebrated by the State. I would like to explain how the State ideology, in the process of projecting a modern and democratic stance, tends to overshadow the resistance and critique of the society. I will summarize different methods of actor training that were instrumental to the development of the NSD institution, and in effect helped produce a genre of plays that celebrates the extravaganza of digital and virtual media, which I will call technology. To support my argument, I will use the example of Abhilash Pillai’s play Helen, performed in 2007-2008 in Bharat Rang Mahotsav, Delhi (and in Tokyo), which was made in collaboration between the Japan Foundation and the National School of Drama.

The formative years of NSD, in the 1960s, depended heavily on the method acting devised by Stanislavski. In India, it was introduced by Ebrahim Alkazi, director of the institution from 1962 to 1977. As director of the prestigious institute, he had the freedom to explore method acting using translations of Greek tragedies as well as Hindi “classic” plays. These plays celebrated male heroes and protagonists who had a grand life. The introduction of Stanislavski’s method acting was also a foreign method of dialogue delivery and awareness of the body that was new to the students of NSD. In 1977, another movement replaced the singular method of actor training in NSD: “Theater of the roots.” It was initiated by B.V. Karanth, who believed in merging the Indian traditional theater techniques with the School’s own method acting. Workshops and collaborations were then organized in the rural and semi-urban areas of India, and local and folk performance traditions were incorporated into the curriculum. The school policies encouraged students who were involved in the performing arts of their own community. Creating a rich and unique identity for India was a major concern at that time. Yet, this program could not be sustained for long, owing to the cultural diversity of Indian society and the homogenous ideology of the State. By the 1990s, another reform opened India to the global market. The government had changed, and capitalism was slowly entering the country. At that time, a faculty member of NSD (Anamika Haksar) brought back method acting, based on socio-realism that she encountered while being trained in the Moscow Art Theater. In negotiating these elements, the theater productions of the time would celebrate technology, deconstruct the individual actor’s ego, and create a democratic space inside the theater. The three major training methods I have just presented set up the context in which the present case study of Abhilash Pillai’s NSD productions take place.

Abhilash Pillai’s engagement with society and culture is reflective and avant-garde. Among numerous NSD productions, Pillai’s work stands out because of its political critiques and the use of technology as an extension of the human body. Having trained under Anamika Haksar, Pillai’s process of theater-making relies on the deconstruction of the bourgeois male hero narrative, and on the creation of a piece that compels the audience to think. In his plays, he merges contemporary issues with the classical texts, divides a character for more than one actor to play, incorporates projections of films and newspaper clips, creates a muddy floor for an image of the filth, etc. The actor’s individual body disappears through this extravaganza. The use of excessive decorum and technology supports an experience where actors are now part of the scenography. The audience is provided with a wholesome experience where they will neither be drowned into catharsis nor will they be constantly made aware of the play devices–creating a non-dramatic discourse. Instead, the piece would showcase new possibilities of human interaction in theater, and provide a critique of current problems as well. For example, Pillai’s play Helen, based on the story of Helen of Troy, subverts many conventions.

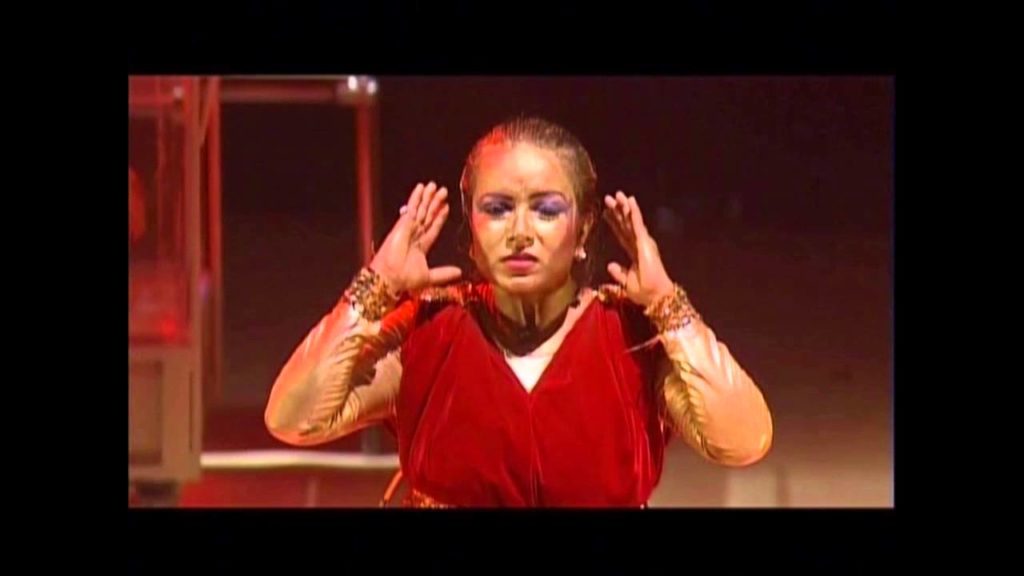

Helen directed by Dr. Abhilash Pillai

This play focuses on women’s oppression by highlighting the abuse and torture of Helen after the Trojan War.

The leadership of Orestes in democratic Greece resembles the leadership of American government during the War on terror. To convey the play’s global nature and to keep it historically unfixed, electric guitars and drums are played by the characters who are dressed in modern attire.

These effects constantly challenge realism. Post-apocalyptic scenography and haunting music contribute to the spatiotemporal non-fixity of the play. It ends with a figure of Helen-1 resembling a Mother goddess held atop the drums, and Helen-2 submerging in the water tank. Thus the play’s concluding last sequence of the play shows Helen submerged, and Helen aloft as Mother goddess.

Since this theater genre became popular at the annual NSD festival, it is interesting to understand the training that students receive in order to take part of such productions.

As mentioned earlier, students’ training at NSD took several turns. Current training provides students with an understanding of new technology as a part of themselves. The 1960s method acting and the 1980s “Theater of the Roots” merged with the New Age concept of socio-realism, creating a training model in which actors learn to infuse their acting with their own personal experiences. They translate the script into their own language and perform amidst projections of new media on stage. This process is crucial since students are meant to learn the craft of theater without being oriented toward producing a show. However, these processes may lead the students to create a script that is aimed at creating a visually spectacular show. Again, actors then become part of the whole, rather than the central attraction of the event. They are trained to merge and transform within the spectacle, as opposed to the obsolete version of the actor standing in the middle of the stage reciting verses. This new training technique demands that the actors act in a specific manner. Even before acting, actors are requested to approach a text, a play, a song, an image, or an idea in a specific way. They are asked to consider how to create a spectacle from the given material. To create this spectacle, the actors are being given basic ingredients in abundance. Having practiced with these ingredients at length, they eventually produce plays with extravagant sets, design, and issues.

However, the actor’s body is not always well versed in responding to the required technology. Those who come with their own cultural past and their own performance practice try to merge themselves into a practice that does not belong to any ethnicity or community. Thus an actor must acquire this technique. However, if this technique becomes the only one and overshadows other ones, it becomes problematic. In many instances, actors bring their own material, including their own knowledge of a certain performance practice, and use it in the production they are working on. For educational purposes and for the purpose of innovation, this knowledge is used and combined with other techniques, foreign texts, and fellow actors. This results in a production that has a certain element of traditional Indian theater, seen alongside modern Western elements and through bodies that do not belong to any culture or society. These bodies on stage are dressed and prepared to show only their eccentric nature, in response to technological devices. They represent global citizenship, a global woman and a global dictator; a postmodern representation of twenty-first-century vices through bodies that no longer carry their own individual social struggle, but a global understanding of political issues.

Finally, let us turn to audience reception. The audience for these play is comprised mostly of people from the urban middle class, with sometimes members of the rural and lower classes of India, and foreign audiences as well. This genre of play is generally produced as part of the national theater festivals or touring abroad for state-run foreign cultural organizations. For an uninitiated viewer, the design and scenography would be mesmerizing. The visual aspect would break the notions of realist/proscenium theater. It directly takes one into the dystopian, phantasmagorical world. The text of the play would be divided into fractions of a story and visuals that would speak louder and show more than the actors themselves. These are the basic ingredients of this genre of play. To attend to all the five senses, Pillai says, “theater is created where neither mind nor heart is the goal to impress; theater should get under the skin of the audience.” [1] With these effects, the audience is indeed impressed–startled and shocked. These plays create scenarios where images matter more than the text, and probably more than anything else. Images of extravagant costumes create more impact than do the actors’ dialogues. Images now carry the essence of the theater. This close relationship with the visual arts and recurring references to art installations demonstrate the expansion of contemporary Indian theater, on a par with global theater production and other art forms as well.

In recent years the NSD Delhi has produced this “genre” of play to the exclusion of all others. Calling it a “genre” is itself is still debatable, since the productions vary from one place to another, from one director to another. But certain common characteristics warrant the use of the term. In these productions showcased by a state-run institution, expenditure is generally high; large amounts are spent on the sets and design. The images are created to give, in Debord’s words, “appearances to essences.” [2] These plays can be seen as a spectacle in which everything is represented or symbolized in order to form another set of images, far removed from reality. These plays, formerly sometimes used as a form of resistance against the State, now become plays that celebrate the power of the State. Since it is funded and showcased by the State, the protest or critique gets dissolved in the extravaganza of lights, fury, and gimmicks. As far as the aesthetics of theater is concerned, these plays do embody a new mode of communication. However, this mode can quickly transition into becoming a puppet of the State’s agenda, with technology eclipsing the ephemerality of the play. Guy Debord explains this phenomenon in The Society Of The Spectacle. From his viewpoint, one can argue that these plays, in which actors merge with the scenography, are no longer plays with a socio-realist ideology. Instead, what occurs is a celebration of the new media and technology. The expertise with which these plays can be produced is showcased. The power of money is also showcased. The State encourages these productions where images of extravaganza are offered, where the subject matter or the theme of the play no longer dictates the production. The old hierarchy is reversed, with images, sets, and technology now being superior forces, and texts and actors becoming secondary.

In the play Helen, an image is created to convey the issue of oil. The text is subverted to show the angst of the women. A lasting image is one of the Mother goddess. On one level, these images convey criticism, but they also convey recuperation. Recuperation can be seen as an assimilation and absorption of a radical idea into a suitable capitalist society. In the play, ideas of resistance are recuperated through the mediation of images. This sort of criticism becomes a tool for the State to propagandize the democratic and open-minded government. In most State-funded plays, the preferred language is Hindi. As per the politics of language in India, the State tries to forcefully implement Hindi as a national language, as opposed to English or any other local language. This is justified by the Hindi-speaking majority of the country. The goal is to create a unique and homogeneous identity for India. The State deploys mechanisms that sift out differences of opinion and conflicting interests. In the case of theater, a homogenous model is being built as well. In this model, the language is Hindi, the texts may be Greek, classical Sanskrit or Hindi, and the design is necessarily extravagant, with a profusion of “special effects.”

Referring again to Guy Debord’s work, I would propose that these performances could be seen as a neo-liberal imagery of the State, making use of technology to create images and spectacles; and that these spectacles overshadow the possible critique and innovative interpretations of texts and acting methods. The money spent in these productions becomes the real protagonist, and other elements tend to serve it. These productions, when they are part of the annual festival of the national theater institution, create the same sense of exhilaration among the audience and in fellow theater-makers. Having become the premiere theater institution in India, NSD inspires the newer generation of playmakers to emulate this kind of production. The relationship between capitalism and theater makes it necessary to present extravagant theater in order to survive in the urban and modern space of India. These productions bear the mark of capitalism from process to performance.

The meaning of theater in India has changed from its conception to the present day. Striving for recognition and a status as a “developed” State, India chooses to produce images and spectacles in many areas: theater, sports, arts, culture, and films. In plays, the body of the actor may come from the rooted practice of a traditional art form, or be trained in other methods of performing arts. Together these bodies produce alien and fragmented characters, serving the larger purpose of creating a spectacle. This “loss” of the actor on stage does not merely mean the deconstruction of the heroic figure, but also the destruction of heterogeneous forms of performing and expressing an idea. The actor has become an extension of technology.

Notes:

[1] http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/how-theater-director-abhilash-pillai-takes-his-plays-and-audience-into-discomfort-zones/.

[2] Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle, Zone Books, New York, 1994, “Separation Perfected.”

References

« National School of Drama,” <http://nsd.gov.in/delhi/>, Accessed February 15, 2015.

Helen (2008) directed by Abhilash Pillai. Video provided by Abhilash Pillai.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books, 1994.

<http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/how-theater-director-abhilash-pillai-takes-his-plays-and-audience-into-discomfort-zones/>, Accessed 22nd May, 2015.

<http://www.jpf.go.jp/e/project/culture/archive/information/0708/08_02.html>, Accessed 22nd May, 2015.

This article appeared in Archee on November 12, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Himalay K. Gohel.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.