Sarah Ellis is the head of digital development at the Royal Shakespeare Company. She first studied music at Goldsmiths University. After finishing her studies, she moved to a digital television company but she quickly went back to the arts. First to a poetry organization called Apples and Snakes. This was a great experience for her where she could work on brilliant projects with writers and theatre practitioners as well as start to look at new ways of performing spoken word. It was there that she first developed her interest in digital: “These were early days but there was a great curiosity among the writers.” From here she went to work at the Albany Theatre. As head of creative programmes, she had the chance to collaborate with different art forms and artists. She also got the opportunity to work as a freelance digital producer at the RSC in 2010. They created a promenade performance with a company called Calvium that brought up many interesting questions about the presence of liveness and digital tools within the performance. Since 2011 she began working full time at the RSC as a digital producer. She developed myShakespeare, which is an online commissioning platform for artists. In 2012, she partnered with Google and created the interactive Midsummer Night’s Dreaming project. In 2013, she was made the head of digital development. A conversation about Shakespeare, theatre, and their relation to new technology.

With the RSC you are now working on a high impact project?

I’m really lucky to work on The Tempest, which has been a two-year process in collaboration with Intel and in association with Imaginarium, (a motion capture and performance capture company). We chose The Tempest because it is Shakespeare’s most innovative play in which Ariel, who is a nymph, takes many forms. It just lends itself to him being a digital character. We are using the performance capture power of Intel’s computer technology so that we will have a live actor to perform Ariel’s movements and then you see the digital character on different projection surfaces: we are treating it a bit like puppetry.

“The key is that you need Prospero to believe that Ariel has that form so the audience can also believe it.”

In this live environment, there are lots of variables and environmental things that could affect the reading of the technology, which is challenging but also exciting.

One of the RSC’s first digital projects, Such Tweet Sorrow, was performed on Twitter. Do you think that Twitter plays can a have a future or it is just a trend?

Some will have a future, some will be just trends, but I think people’s behavior is changing quickly. You need to know why you are doing it. Our Twitter-play was very early on in the development of social media. It was an experiment in how can you put one play as a conversation between those characters who are involved. There were people who stuck with it for six weeks, a loyal and core audience. But we also shouldn’t forget about how to keep our own core audience. I think the audience in the last five years has become much more comfortable with stories appearing in different spaces. Such Tweet Sorrow was about curiosity for the Twitter space.

Are these platforms enough to create a participative attitude from the audience? They can be interactive but how do you influence your audience towards more interactivity? Is this about dramaturgy?

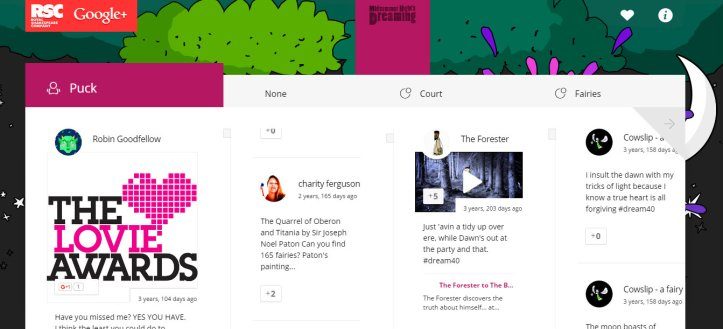

The question is when do you want to make your audience more interactive. For example, when is the RSC experience starting, when you’re buying a ticket? I would say, when you want, you can make your audience be participative but you can also let them just sit there and experience. In 2013, when we made Midsummer Night’s Dreaming, we invited people to participate in the show and upload content: this demonstrated the audience’s creativity and participation. They kept on their devices through the show. We performed this show for 3 days online and live. Although Midsummer Night’s Dream runs as three and a half hour as a play, the action of the play takes place over three days. The key scenes were performed when they should have been performed in the play – in the venue or in places around the venue. People wanted to take part so in the gaps between the RSC performance we opened an online platform through social media channels. We created online characters. We told the story that is going on and we uploaded content. We got 2000 pieces of commissioned content and 1000 pieces of public content: that was interactive. From the dramaturgical perspective, the text didn’t change, the outcome of the play didn’t change. What changed was how the world of the play existed. You can very much have interactive and participatory online work, but you have to know why are you asking them to do it, and what do they get from that experience.

Midsummer Night’s Dreaming Project

Was it changing something in the play when they were uploading?

No, it wasn’t changing the core text. We created characters that we thought might be standing on the edges of the play. So, for example, there was Mr. Snug in the play and we had created the character Mrs. Snug, which makes sense in the play and what the audience got from it was that they were part of the fun, and they could make stories around the play.

This is the performance for which you partnered with Google. What do partnerships in this context mean?

We were doing all sorts of fun things. The partnership was exploring two questions: how can you extend the borders of the RSC and what would theatre look like online today? We explored that and it was a huge experience for both of the companies. The process of what happens behind the scene is also just as impactful.

What was the outcome?

We reached 13 million people on social media. That really made the organization think about what the social networks and their communities’ importance are. We are now reaching far more people online through our marketing or audience focused channels.

Sarah Ellis, the head of digital development at the Royal Shakespeare Company

How do you see the digital interpretation of Shakespeare’s performances nowadays?

I see lots of different people using digital ways to tell their stories about Shakespeare. We did a series of commissions, but we also invited people to show their own digital interpretations. I think it speaks to the market: there is a hugely diverse range of interpretation of Shakespeare through YouTube and other different online platforms. It is the voice of the many, which the online platforms demonstrate, and you are able to see that. You are able to connect: people are really playing Shakespeare differently.

So you think that this is the 21st century’s way to explore Shakespeare’s play, who we might also call an experience designer?

Certainly, Shakespeare was an innovator, and if you look at the Tempest, there was a lot of technological innovation. Also, the technology changes the form of the theatre. Shakespeare was at the heart of lots of transformational and political change. He was always exploring and innovating in his work. I think the digital age we are now in is a similar exploratory time like James Shapiro writes about in his book ’1599,’ or for instance India’s colonization, that brought stories from around the world. We get this now with the Internet. We go in cycles like that and the great thing about using Shakespeare’s work over the past 400 years is how people have innovated with those texts and used his words to talk about the world today. For example, we see this through his history plays, through the different interpretations in different cultures of his plays: people tell their story, their community story. This is interesting for digital and non-digital spaces.

Is audience attention more fragmented because of the digital technology?

I think we’ll lose the D-word: we will lose that digital is ‘other,’ ‘different,’ or ‘new.’ This will change and a lot will become normal. People’s performance space can be anywhere, they will have different meeting points where culture is going on. I think there will be a place for online performances. Because of the mixed economy, we have got a lot more choices.

This is actually how you see that it will be in 30 years?

Potentially. Society is so embedded in being able to experience something on a laptop or a phone. We no longer belong to that generation that has just one place to see theatre. This is already everywhere.

20 years ago was not like this?

We just now have different tools, and they are changing and will change in 30 years, and we will have access in the next 30 years to things that we do not have now. We may not think it possible but phones might not be so useful anymore.

Will people be more concerned related to the performance of their own data? Will this change the audience’s attitude? I mean now everyone is eager to check in from a theatre?

It might not be so contagious, but I am certainly sure that the next generation will come together around those bytes and data, come together around understanding it in a sophisticated way. It will be a live debate.

Was it a relevant question for you in 2013?

Yes, it was, and we made a certain decision based on that: with all the artists that we commissioned, we talk it through with them that we cannot protect their IP, so we cannot ensure the privacy of the information from where they are going to go online: so we paid them an amount that we thought is representative of that. And we didn’t charge people to experience the project online or to see the shows. There was no monetization. That was a decision that we took in order to experiment with this world and it has not been completely solved yet in so many different areas.

This article was originally published in the ZipScene Magazine. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ágnes Bakk.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.