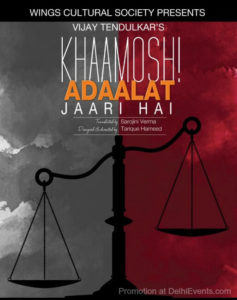

With its debut production of Jaisi Karni Waisi Bharni presented at the 21st Urdu Drama Festival in 2010, over the years, Wings Cultural Society has established itself as a meaningful amateur group in the theatre world. Under the leadership of Tarique Hameed, a gifted theatre artist, its productions have featured at several prestigious theatre festivals including Bhartendu Natya Mahotsav, organized annually by Sahitya Kala Parishad, Delhi, and Bharat Rang Mahotsav.

In its latest production of Vijay Tendulkar’s Shantata! Court Chalu Ahe (1968) in Sarojini Verma’s Hindi translation from Marathi as Kamosh! Adaalat Jaari Hai, which was presented at New Delhi’s Shri Ram Centre recently, some young actors got the opportunity to perform for the first time after participating in the workshop for a month. Despite a few flagging patches in the initial sequences, the production acquired momentum, offering the audience engrossing viewing experience.

Directed by Tarique Hameed, Kamosh! Adaalat Jaari Hai is a significant play in the history of modern Indian drama which has been translated into several Indian languages and staged by veterans as well as amateur directors. In Delhi, we have seen several mesmerizing presentations of the play. Tarique’s production is not a carbon copy of earlier successful productions. He attempted to introduce some innovative elements. He has used a few flashback scenes between Benare, the protagonist, and Ponkshe who rejects her proposal to marry her, confessing that she is pregnant. There is another flashback scene between Benare and her lover Prof. Damle who treats her in a heartless manner when Benare reveals to him about her pregnancy. Both are having a relationship. Rather than sympathizing with her condition, Prof. Damle blatantly refused to take any responsibility. He expresses no moral qualms when she says that she will commit suicide. The director has used these flashback scenes in an intricate manner to interplay two conflicting views – one expressed by Benare and other by her tormentors which results in the deepening of the characterization. Here is the picture of a patriarchal society where women are treated like a commodity.

Directed by Tarique Hameed, Kamosh! Adaalat Jaari Hai is a significant play in the history of modern Indian drama which has been translated into several Indian languages and staged by veterans as well as amateur directors. In Delhi, we have seen several mesmerizing presentations of the play. Tarique’s production is not a carbon copy of earlier successful productions. He attempted to introduce some innovative elements. He has used a few flashback scenes between Benare, the protagonist, and Ponkshe who rejects her proposal to marry her, confessing that she is pregnant. There is another flashback scene between Benare and her lover Prof. Damle who treats her in a heartless manner when Benare reveals to him about her pregnancy. Both are having a relationship. Rather than sympathizing with her condition, Prof. Damle blatantly refused to take any responsibility. He expresses no moral qualms when she says that she will commit suicide. The director has used these flashback scenes in an intricate manner to interplay two conflicting views – one expressed by Benare and other by her tormentors which results in the deepening of the characterization. Here is the picture of a patriarchal society where women are treated like a commodity.

Tarique has cast a large number of performers while the play needs about eight actors. He has cast different actors to play the same character in different acts. This experiment tends to make delineation of characters superficial, obstructing building the tension essential to reveal the inner life of the characters. At times this device disturbs the flow of the rhythm of the dramatic action. However, the casting of two seasoned actors enabled the production to retain its engaging power.

Khamosh! Adaalat follows the structure of a drama-within-the drama. Tendulkar used Durrematt’s A Dangerous Game as a springboard but Shantata is very much his own play. The play opens with the rehearsal scene. The artists start coming, their approach to the rehearsal seems to be casual. A happy-go-lucky atmosphere prevails. Finally, the rehearsal starts and the door to the rehearsal room gets bolted from outside forcing the participants to remain confined to the room so long as somebody opens the door from outside. The rehearsal is about a play in which a woman is being tried for aborting her fetus and hence she is a murderer. The mock court starts working.

Initially, the atmosphere is light-hearted. The performers indulge in making fun of one another. But soon there is interplay between the contradictory perception of Benare who is cast in the role of the woman alleged to have aborted her child and the witnesses before the judge. The witnesses try to convince the judge that Benare is guilty of infanticide. The witnesses give their statements in mocking and hostile tone. Benare standing in the dock as the accused brushes aside these charges as baseless. But the tone of the witnesses becomes more aggressive, full of insinuations.

One of the witnesses says that he saw the accused woman, who is a teacher, talking to Prof. Damle in a pitiable voice, beseeching him to save her honor. Then comes another witness who gives statement that aims at damaging the reputation of Benare. According to him, she is pregnant and wanted to marry him. A third witness says she tried to seduce him with a view to marry him.

The imaginary world of theatrical art turns out to be the reality of the life of Benare. She breaks down, stepping out of her character, Benare narrates her own tormented life deceived by two men – her maternal uncle when she was just 14-years old and by Prof. Damle whom she adored as a scholar. Some of the members of the group say in a sympathetic voice, “Don’t be upset. After all, it is just a drama, not real life.”

In the climactic scene, a shocked silence prevails. The character of Samant moves slowly and slowly towards Benare, stands with her, without speaking a word – subtlety suggesting that Benare in her critical situation in a stony-hearted world is after all not alone.

Rochana More as Benare invests her role with intense emotional power. Her Benare is initially a carefree woman in a playful mood but as she confronts the witnesses, mocking her, raising questions about her character, her mask of a happy woman is torn and becomes tense, revealing her life as a teacher who loves her profession, exposing those men whom she loved but betrayed her. Shilpa Gupta as Mrs. Kashikar, frivolous wife of the judge, imparts some lighter moments to the production.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Diwan Singh Bajeli.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.