Much of my approach to theatre, to performance, especially, consists in locating and assessing a production’s center of gravity; that is, what are the dominating forces at work in realizing an abstract and (more or less) lifeless script into living theatre? Most often in contemporary theatre, that driving force is the director, although at times the producer may override directorial prerogatives. Alternately, a dominant actor may drive the performative realization so that he or she can mark the production as their own. That seems to have been the case with the Lincoln Center revival of Waiting for Godot in 1988, under the direction of Mike Nichols but featuring Steve Martin and Robin Williams. The least bankable actor in that troupe was the near-contortionist, an actor, like the principals, also celebrated for his physical clowning, Bill Irwin, who played Lucky. Martin and Williams were the attraction, and they were irrepressible: it was their show. Irwin the apprentice would come into his own some two decades later. More rarely, a designer may indelibly stamp a production and thus force certain performative outcomes. Various examples of such are possible (including some of my own stagings), but the one that comes to mind in relation to the production under review here is the 2009 Broadway revival of Waiting for Godot by the Roundabout Theater Company at Studio 54, directed by Beckett stalwart and sometime collaborator, Anthony Page, in which designer Santo Loquasto’s wall of stone set constricted all but the most minimal movement, restricting stage space to about one-quarter of its potential.

With Samuel Beckett, the production’s creative collaborators’ respect for the author tends to dominate, in part, at least, because the owners of Beckett’s work impose legal restrictions on possible shifts in the center of gravity. Page should have been the driving force of this 2009 Broadway revival, having worked closely with Beckett for the first London revival at the Royal Court Theatre in 1964 (a production too often mistakenly deemed the first uncensored London production – it was not), and Bill Irwin was establishing himself as his generation’s Beckett actor at Studio 54. However, the Academy Award-nominated, Tony-award winning, American Theater Hall of Fame inductee (2004) Loquasto seems to have imposed his will on the production’s star-studded Broadway team. The simplicity of a “country road” was replaced by something of a granite fortress. There are egos involved in theatre, and there must have been a “But this is how I see it” moment in 2009. That’s how the power structure of Broadway’s commercial, investor-focused, hit-driven theater works. In the talk-back after the 2009 revival, Broadway stalwart Nathan Lane kept shouting, “We have a hit.”

Broadway revival of Waiting for Godot (2009): L-R, John Glover (Lucky), Bill Irwin (Vladimir), Nathan Lane (Estragon), John Goodman (Pozzo) (Photo Sara Krulwich for The New York Times).

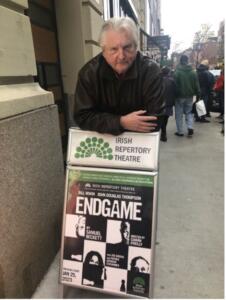

Irwin would go on to create and perform an eighty-minute, Jackie McGowran-like, one-man anthology piece On Beckett: Exploring the Works of Samuel Beckett under the auspices of New York’s Irish Repertory Theatre. It showed at San Francisco’s ACT (American Conservatory Theater) in 2018, and in New York it would win the Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Alternative Theatrical Experience, but performances were limited by COVID-19 restrictions, which led IRT (Irish Repertory Theatre) to develop an On Beckett / In Screen version of the show, which premiered 17 November 2020, as part of IRT’s Digital Fall Season (trailer at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=om0zRTjEEVM).

By January 2023, COVID-19 still lurking, New York theaters were open for business, with masks optional, and the city launched its first ever Irish theatre festival featuring a clutch of off-Broadway theatres. Called “Origin 1st Irish,” the initiative was spearheaded by the Origin Theatre Company. One of IRT’s contributions was a revival of Endgame, with John Douglass Thompson as Hamm, Joe Grifasi as Nagg, Patrice Johnson Chevannes as Nell, featuring Bill Irwin as Clov, and directed by IRT’s co-founder (with Charlotte Moore) and producing director, Ciarán O’Reilly (25 January-12 March 2023). Designer Corcoran took full advantage of the natural architecture of the main stage of this small, pocket theatre to adapt Beckett’s set to the immovables of the IRT stage, so both windows were on the back wall and were not facing polar opposite directions, for example.

While the production was still in preview when I saw it, the performance was nonetheless highly polished and seamless. As the sole mobile character, Irwin as Clov demonstrated his stage command and distinct quirks of movement to full advantage. He moved with studied stiffness, seemed perpetually tilted, constantly in need of support, leaning on whatever prop was to hand; his ascent of the ladder, in particular, was something of a ballet as he whipped his left leg over the top of the ladder to add another element of bodily support. It was a masterclass in stage movement, but it was equally clear that Clov could not function outside the shelter, and he was one fall away from total immobility himself. Nagg and Nell, a multi-racial couple, were credible humans with a genuine attachment to each other and an ambiguous relationship to their mixed-race child. The racial element is an instance of contemporary color-blind casting so that any racial divide is to be deemed invisible, by convention, as in the all-Black revival of Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth at New York’s Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center, 25 April-29 May 2022, directed by Lileana Blain-Cru. But the racial difference (even if conceptually unseen) does put one in mind of the controversial mixed-race production of the play directed by JoAnne Akalaitis at the American Repertory Theater in 1984. When he could not stop that production entirely, Beckett demanded a program note insertion that declared the staging “a travesty.” To this reviewer Beckett’s objections missed the brilliance of this subterranean staging, his response a total misreading of the production, the result of undue influence by those who had vested interests and had Beckett’s ear.[i]

Endgame American Repertory Theater (1984). L-R, Ben Halley, Jr. (Hamm), John Bottoms (Clov) (Photo Richard Feldman for ART)

2023 is another matter altogether, since the set was not an abandoned subway car but the back wall of IRT’s mainstage, and the convention of color-blind casting now well established. But the IRT mainstage has no formal proscenium and hence no curtain, so performance began with a prolonged blackout to get the actors in place, and those preparations were masked by “original music” by sound designer Florian Staab. And lighting designer Michael Gottlieb could not resist using light changes to enhance certain moods and to spotlight Hamm during his monologues, overriding Beckett’s “Grey light,” highlighted (if that’s the word) by Clov’s “Gray! […] Light black. From pole to pole.” And Beckett’s “Bare interior” was overridden by designer Charlie Corcoran with some David Belasco-like naturalistic bric-a-brac.

But on the whole, this was Beckett’s play – not O’Reilly’s, Irwin’s or any of the designers’ – and the cast and crew were committed both to a faithful and a fresh staging. Irwin was flawless in motion and verbal nuance. If one were to carp, one might suggest that John Douglas Thompson’s Hamm was too unmodulated as he tended to shout almost every line. His repeated halting of Clov’s exit with “Wait” seemed to have been delivered without understanding that he is systematically preventing Clov from retreating to his sanctuary. And his “chronicle,” the story of the intrusive beggar asking for bread for “my little one [. . .] My little boy,” who may be Clov, is not delivered as a carefully crafted, well-rehearsed play within a play, complete with multiple voices as Beckett had it in his staging, Hamm leaning over almost touching the floor to address the prostrate beggar. Thompson recites it as a straight monologue. In contrast, Nagg’s tailor story, another play within the play, was nuanced and performed as a little playlet. And Hamm’s gaff with its ludicrously outsized metal hook capable of bringing a shark to bay (“Wait! […] Will there be sharks, do you think?”) tends to be parodic, unintentionally, I expect.

What was missing, then, were the nuances that Beckett added to his own productions, all recorded in his published theatrical notebooks and easily available in new, moderately priced, paperback editions from Grove Press (offices just down the street from IRT) and Faber and Faber.[i] O’Reilly and/or Irwin chose to work from the standard, unrevised Grove Press edition, however. The result was a series of missed opportunities: the return of Hamm to the center of the room (or the center of the universe?) after his turn around the world is both more aggressive and more playful in Beckett’s reworked revisions; for Beckett, one of Clov’s inspection of the without through the window is faked, some of his movement likewise; the alarm clock held by Clov symmetrically between his and Hamm’s faces, a scene Beckett tended to call “three faces,” is lost. An empty picture frame remains on the wall (stage right here) – Beckett had cut it – and at IRT Clov replaces the empty frame with the alarm clock instead of first placing it on Nagg’s bin lid, then, realizing he could knock it off when he emerges, moves it Nell’s, a knowing signal that she has died.

Endgame, IRT 2023, L-R, Bill Irwin (Clov), John Douglas Thompson (Hamm) (Photo Marsha Gontarski)

These nuances, the products of Beckett’s intense work on the play in performance, are minor in themselves, but collectively, they enhance the play and develop the relationship between master and slave, father and son. Such post-publication refinements by Beckett were absent in IRT’s staging – to some loss. That said, this production had a vitality, a credibility, a humanity, and its own originality, much of that credited to Irwin’s physicality and vocal dexterity. He is the play’s mobility even as he, too, is at his last. One would hope as the theatre world returns to its pre-Covid state, this production, which generated a standing ovation from the audience, will go on tour to attract a new generation to Beckett’s theater.

Endgame, IRT 2023, L-R, Bill Irwin (Clov), John Douglas Thompson (Hamm) (Photo Marsha Gontarski)

Photo of the author, Marsha Gontarski.

Published in cooperation with the Between.Pomiędzy Research Group, University of Gdańsk, Poland.

[i] The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett, Vol. II, Endgame. Ed. with an Introduction and notes by S. E. Gontarski. London: Faber and Faber, 1992 and New York: Grove Press, 1992, 2019.

[i] See further: https://americanrepertorytheater.org/shows-events/endgame/

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by S.E. Gontarski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.