On a recent trip to Sweden to interview the playwright Jonas Hassen Khemiri, whose plays are now translated and performed across Europe and North America, I was invited to attend two premieres in the country’s city theatres in Gothenburg and Uppsala. I was thrilled to discover two sophisticated stagings of classical plays by two of the most dynamic and experimental directors working in Scandinavia today, Yana Ross and Kjersti Horn.

Yana Ross’ new production of A Doll’s House (Ett Dockhem) at the Gothenburg Stadsteater has generated enormous interest across Sweden, cementing her influence and popularity in Scandinavian theatre. Ross uses therapy as a framing method for her original rewriting of Ibsen’s canonical text. Rank is reimagined as a psychiatrist who uses role play as a form of analysis. In the opening moments, the audience is led to believe that Rank is Torvald, when in fact he is merely playing the role of Nora’s husband in an imagined scenario. He invites Nora to analyze her choices and attachments; this metanarrative reveals that this is not so much a deconstruction of A Doll’s House as a form of performance analysis, a theatrical essay of sorts. There is a dubious ambiguity to Rank’s role-playing, however, which from the outset demonstrates the compliance demanded of Nora in her role as patient, apparently for her own benefit (psychiatry).

Ross’ doll’s house is a moveable box made of large glass panels with an interior of sleek and simple furniture (“tasteful but not extravagant”) in muted colours that are sharply punctuated by dabs of bright red (a color that Nora will wear later as a reference to Sleeping Beauty or Little Red Riding Hood). The presence of a technician who films the action from outside the house reinforces our sense of being an eavesdropper or voyeur. Despite being enclosed, the crystal clear audio of the actor’s voices is reminiscent of Krzysztof Warlikowski’s (A)pollonia, in which visually we feel distanced or separated from the actors while acoustically we experience their extreme proximity. As the box moves around Gothenburg’s large main stage the bedrooms of the Helmer home are revealed on the opposing sides of the sitting room. The pale white and gray interior of the parent’s bedroom is juxtaposed with the children’s room, whose walls are vividly painted with jungle animals. The children are never present on stage–indeed, we only encounter them briefly through a Facetime call–and yet their bedroom is consistently occupied by drunken and erotic encounters. This misuse of the children’s room strongly reinforces the metaphor of a doll’s house, a structure that encapsulates children’s ideals of a domestic space that coalesce with Ross’ connections between Ibsen and Disney.

Kristine Linde is made into a man’s role (Kirster Linder), which shifts the gender dynamics of the entire cast. Nora is the only woman on stage, surrounded by a quartet of close male friends (Torvald, Rank, Korgstad, Linde). Her isolation is thus redoubled between her home and social world, which Ross deftly reframes through a Disney fantasy. We first encounter this reference as the house spins on stage and the four men first break the (literal) fourth wall by stepping through the house’s glass walls to move to a contemporary rhythmic rendition of the seven dwarves anthem to the pleasures of manual work, “Hi-Ho, it’s off to work we go!,” that is both suggestive of male sexuality and labor. The concept of role-playing is playfully extended into the Helmer’s sex life when Nora dresses up as Snow White and Torvald as one of her naughty dwarves, who needs to be whipped and punished. The quartet of men all become key players in the fantasy, the dwarves who simultaneously perpetuate the fantasy of the female sublime (a nod to Ewig-Weibliche) and male exclusivity while sexualizing female power. Even if the men compete with one another they form a bond that remains impenetrable to Nora, thus reiterating the distance that separates the collective of workers from the sublime female in Snow White. Even Nora’s binge eating becomes a game that undergirds and reassures male bonding. Ross’ neat turn is here is to sexualize the men themselves. They begin the tarantella, an erotically charged cheerleading routine with pom-poms. Nora joins them, following their lead and rehearsing their moves. Rather than suggesting a critique of gender norms in which women follow the idealized lead set out for them by men, this inverts the question of male sexuality, not only offering a comical take on homo-erotic bonding rituals but also asking to what extent male desire might be caught up in the erotic display of their own bodies. The tarantella thus reveals a side to sexuality that is normally repressed, but (as in the therapeutic role-playing scenes and the Snow White games, or when the men dry hump one another to Beyoncé’s Naughty Girl) it is not Nora’s hidden character that is revealed so much as the male social world she must negotiate.

A Doll’s House. Photo by Mikko Waltari

The whole question of racism is frequently left out of stagings of the play, and Torvald’s offensive line about knitting having a “Chinese effect” is typically cut rather than explored. Ross cast Gizem Erdogan, a Swedish actress of Turkish descent, in the role of Nora. As Theresa Smalec has argued, Nora’s ethnicity is often assumed to be white and Scandinavian, like Torvald’s. Smalec asks: “How does her cultural background make her a different ‘monster’ from her husband?” [1] Ethnicity is carefully interrogated through apparently innocuous slurs that eventually culminate in a racist tirade. Torvald reminds Nora that it is time for her upper-lip wax, thus criticizing her attractiveness and femininity through a veiled reference to ethnicity. When Torvald discovers Nora’s secret loan, however, his suppressed racism surfaces to the top: “You are a crook, a criminal, a total disgrace, calling yourself ‘third generation’ but really you are a dirty Turk!” Economic anxieties and correlated concepts of selfhood are thus racialized. Generational migrant identity, as well as ongoing problems of racism, are topics that continue to dominate Swedish public discourse around national identity, which Ross integrates skillfully into this paradigmatic Scandinavian text. There are other passing references to diversity and social equality, such as Rank’s equation of political correctness with moral decay, and his dismissal of the Swedish “nanny” state, which he condemns as “turning our nation into a hospital.” Later, the audience laughs when Torvald exclaims, “Are you saying I’m not a fucking feminist? That’s ridiculous! I am Swedish, we are all born feminists.” Torvald’s chauvinism and Rank’s conservatism provocatively disturbs easy associations of Swedish society with welfare support, gender equality, peaceful civil society, and tolerance to diversity.

After we learn that Rank is dying of cancer, we see him imagine (play acting as Torvald) a long life with Nora, in which he urges her to have another child. Not only does this suggest that Rank is in denial about his own impending death, it also intimates an erotic triangulation between the psychiatrist and the couple. This impression is strengthened when a potential threesome develops. Nora and Torvald have sex on their couch while Torvald holds onto Rank’s hand and the men share an intimate contact in place of husband and wife. As a result, when Nora is impregnated the psychiatrist is implicated in the creation of this new life (the two men have produced this child). Nora’s refusal to give birth draws attention to mothering as labor and her denial of male entitlement–”it might be a boy”–and (perhaps) a refusal to reproduce a new generation who will also fall victim to racism.

The notion that freedom is sacrificed when one goes into debt is also reinterpreted. The door does not slam behind Nora in this production. Her intention to leave is framed through her refusal to be reflected through the mirror of a man (thus citing the opening role-playing scene in which Nora’s emotional life is reflected through her psychiatrist’s game). However, in the final moments of the performance, the men extract themselves from the home, looking as if they are landing on the moon, walking outside of the gravitational forces of the domestic space. They dress Nora as Sleeping Beauty, an infantilizing gesture that makes her look like one of the children. (What’s more, the whiteness of this fictional character is highlighted as a form of ethnic drag.) The house sinks into the stage as they spin a final dance, reminiscent of an early Hollywood musical, or–more recently–the dream sequence in Damien Chazelle’s La La Land (2016), while lip-syncing to Once Upon A Dream from Disney’s Sleeping Beauty (1959), putting Nora herself to sleep. In a moment of supreme irony for a play that is perhaps best well known for its ending, the final line of the performance (also taken from the animated film) is “Oh, I just love happy endings!” Ross–explicitly referencing Elfriede Jelinek’s rewriting of these fairytales–thus places at risk our own complacency in accepting Nora’s slamming door with naïve optimism as a “happy ending.” The notion of debt–already ambivalent in the original text–linked to Nora’s departure from the Helmer household renders her future economically uncertain. Her departure from her home is thus also highly suggestive of previous acts (and conditions) of migration that precede the story of a “third generation” Swede. Nora’s refusal to give birth to her child also dissipates when she is lulled into dreamless sleep.

From Gothenburg, I made my way to the Uppsala Stadsteater. For Petra Brylander, the artistic director and CEO of the theatre, gender was at the center of the casting choice of a new production of Richard III. As the theatre’s first female artistic director and business manager, Brylander has worked hard to open new casting possibilities for women and to explore alternative forms of gender representation. She invited Norwegian Kjersti Horn to direct Richard, whom both directors felt should be played by a woman. Brylander was excited by Horn’s approach, which offers more horizontally oriented power relations than many directors.

“Horn is the opposite of Ingmar Bergman,” Bryland told me. “She is really open to ideas; she works with the actors and takes their ideas on board. Bergman used to lead his actors by the hand.”

2018 marks the Bergman centenary in Sweden and there will be productions of his plays and stage adaptations of his films across the country. As a result, the iconic Swedish director is on everyone’s mind at the moment. (Uppsala is also participating–having previously produced a very successful version of Scenes From A Marriage, the theatre will take on a huge challenge for the centenary with an adaptation of Seventh Seal that will open in November 2018.)

The scenographer and set designer Sven Haraldsson told me that he started with the shell of the set, which was on a raked stage with white panels that the actors burst through over the course of the action. All further set elements and props were then added during the rehearsal process, right up until the premiere. This mode of working makes Horn’s productions dynamic and changeable. I saw the final technical rehearsal and in a discussion with Haraldsson and dramaturg Marie Persson Hedenius I was told that the play’s ending could still change on opening night. This level of freedom is something that may not be common on Swedish stages, but which is enabled through a repertory system that allows for such high levels of responsive experimentation.

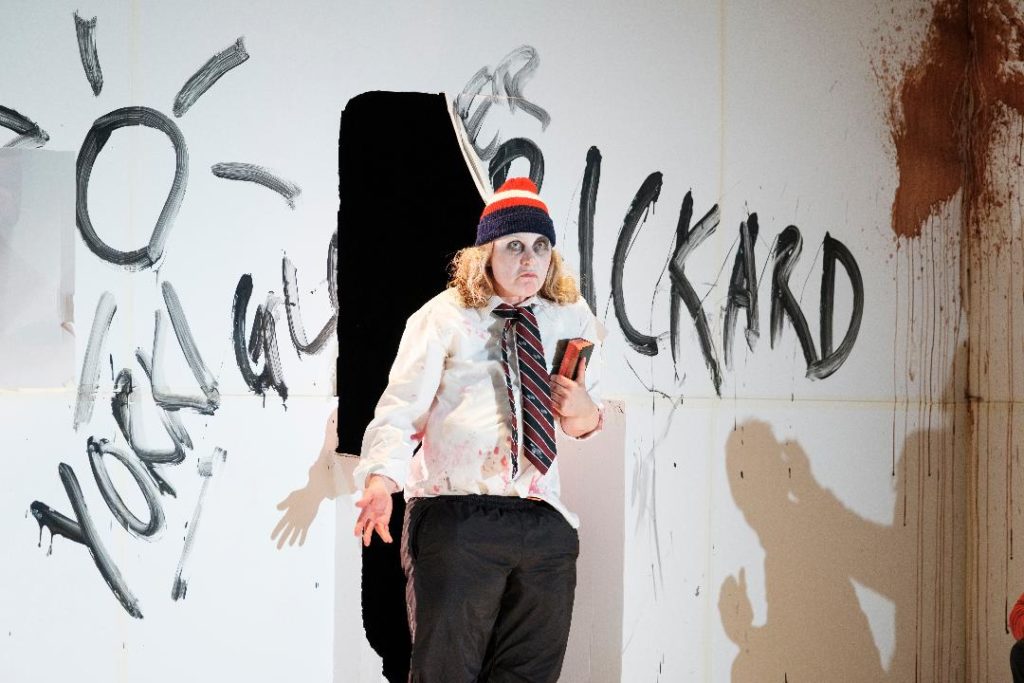

Before rehearsals, Horn heavily edited the script and chose only six actors to play the nearly 60 roles in the play’s extensive cast list. All the actors play multiple roles except Eva Melander, a very well known actress from Swedish television, who is Richard. Appearing in a fat suit with white face make-up and a blackened eye, her ill-fitting men’s clothes are topped with a red, white, and blue sock hat. My first and enduring impression was somewhere between the grubby, mischievous, foul-mouthed humor of Michael Keeton’s Beetlejuice and the teetering pathetic villainy of Danny DeVito’s Penguin. When she enters the set she is the only color in a raised pure white triangle. Richard’s opening speech is punctuated by expletives that indicates how freely the creative team has played with translation. This is no sacrosanct production of a Shakespeare classic. Just as Thomas Ostermeier interrogated audience empathy in his production of the play starring Lars Eidinger in the title role, Melander’s Richard is personable and difficult to dislike. Horn explained that on the one hand she was drawn to play was to explore questions around disability. The director feels that non-normative and differently abled bodies are still under-represented in Scandinavian theatres, and she was adverse to stereotypical depictions of the English king. Separately, she was concerned with audience reception.

“It is easy not to empathize with Richard,” Horn commented. “But I want the audience to look at this character and really ask themselves, ‘What in him is in me?’ The answer to this comes to us as a kind of violence.”

Richard III. Photo by Micke Sandström

In the opening scene, Richard explains the War of the Roses to the audience, drawing family trees directly on the pristine white walls to catch us up on the complicated details of the family lines that connect and intersect the Houses of York and Lancaster. As the gruesome plot unfolds the white space becomes covered in black paint, blood, and glitter. The walls themselves are punched open by each of the actor’s entrances, beginning with Clarence’s bold kick, and are eventually used weapons by the characters to attack one another–thus making the methodology of deconstruction architectural, as metaphorically suggested by Derrida. The actors dress and undress, largely visible through the broken walls, throwing on wigs and coats. Their physical and vocal precision makes each of their characters instantly recognizable, which is no small feat. This made me reflect on previous productions that have large casts wearing similar costumes and playing in a singular performance register. Against this tradition, Horn’s casting choices–and the skill of the ensemble–helped to disaggregate this complex network of courtly personages.

While Queen Margaret is rendered as a chain-smoking, faded glamour star a la Bette Davis, Anne is slim and sexy in leopard print tights. She drags her husband’s corpse onto the stage and sets out two votive candles. The corpse is doused with fake blood–a recurring stage strategy for each of the many deaths–which burns brightly on the powdery white stage before drying into a rusty brown. Playing the famous Anne/Richard scene with two women changed the dynamic. Richard, on her knees, nips at Anne’s bottom with playful sexuality rather than earnest eroticism. Anne’s mouth is also covered in bright fake blood, which intensifies both the potential humor and tragedy of this very strange encounter. When the scene is finished the corpse is kicked off stage, signifying the lack of respect with which the dead are treated and the speed with which they are forgotten. The disposability of bodies returns in a horrific moment later in the production when Anne dances for Richard, topless under a red light, drinking until she passes out. Richard throws herself on top of Anne’s unconscious body and grinds against her, provoking uncomfortable laughter from the audience. Richard then sprays foam over Anne and the laughter stops. This is an interesting effect of the gendered casting. I have the impression that a man in the same role would not have induced laughter from a “play” rape scene–but the stage metaphor for semen appeared to return the audience to the reality of sexual violence. Anne is then covered with a glittering mantel, formerly worn by Elizabeth, and the court returns, stepping carelessly over her body. Is she dead or is she drunk? The question is horrifying.

The most moving intervention into the text is the final scene. The letters “RIC” are written in red on the wall. How will the word be completed? Richard or Richmond? We wait to see. Eventually, it is the latter. Slowly the stage fills with foam–the metaphor for semen taking on new proportions–through which Richard plunges in and out. The foam cleans the blood on the stage, but as Richard wrestles with her invisible ghosts, sticking her sword in every direction, a fresh bucket of blood lands on her head. The foam turns red as we hear a sound reminiscent of snow, a metaphor for renewal. The King is dead. Long live the King.

Footnote:

- Theresa Smalec, Yelena Gluzman’s I’m Sorry For Everything, TDR 47.3 (2003), pp. 136-143, quotation on p. 141. Italics in original.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Bryce Lease.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.