Disclaimer: I was Jeremy’s teacher at Yale during the time he wrote Slave Play, so this isn’t a traditional critical review and should not be used as such; rather, it’s a continuation of the conversation on gender, race, and power that was happening at the time in our classroom and on campus.

Spoilers alert!

In her 2011 book, Techniques of Pleasure: BDSM and the Circuits of Sexuality, Margot Weiss, an anthropologist, links BDSM games to the complex nexus of socioeconomic power relations, involving gender, race, economic and social status, and whatever else might affect the distribution of power in human affairs. Doing much of her research in the San Francisco underground BDSM scene of the early 2000s, Weiss discovered three aspects of sexual fantasy: one, since power doesn’t exist in a vacuum but is manufactured by the econo-symbolic system of signs and signifiers, sexual play must necessarily parallel – or reverse – pre-existing power relations: you perform the real-life situation of unequal power distribution (white cop / Black driver, male CEO / female secretary, or vice versa). Two, for the socially, economically, or culturally disempowered, the spectacle of abasement can have a quasi-emancipatory effect: unlike in real life, where one cannot escape from the indignities and dangers of everyday life, in the controlled environment of structured sex play, not only can one can escape the humiliating and dangerous situation (the safe word stops the game at any time); one can also reverse the roles. And three, by enacting the spectacle of your abjection, you not only enact your rescue but also learn how to psychologically manage your emotions (of fear, fury, disgust, anger, humiliation, etc.), helping you to cope with whatever real-life throws at you. Thus, for the marginalized, BDSM can function not so much as fantasy but as mimesis of the real-life nightmare from which one has a capacity to wake up. (Hence the faux premise of Freudian mythology: women don’t fantasize about violence but rather about an escape from it.)

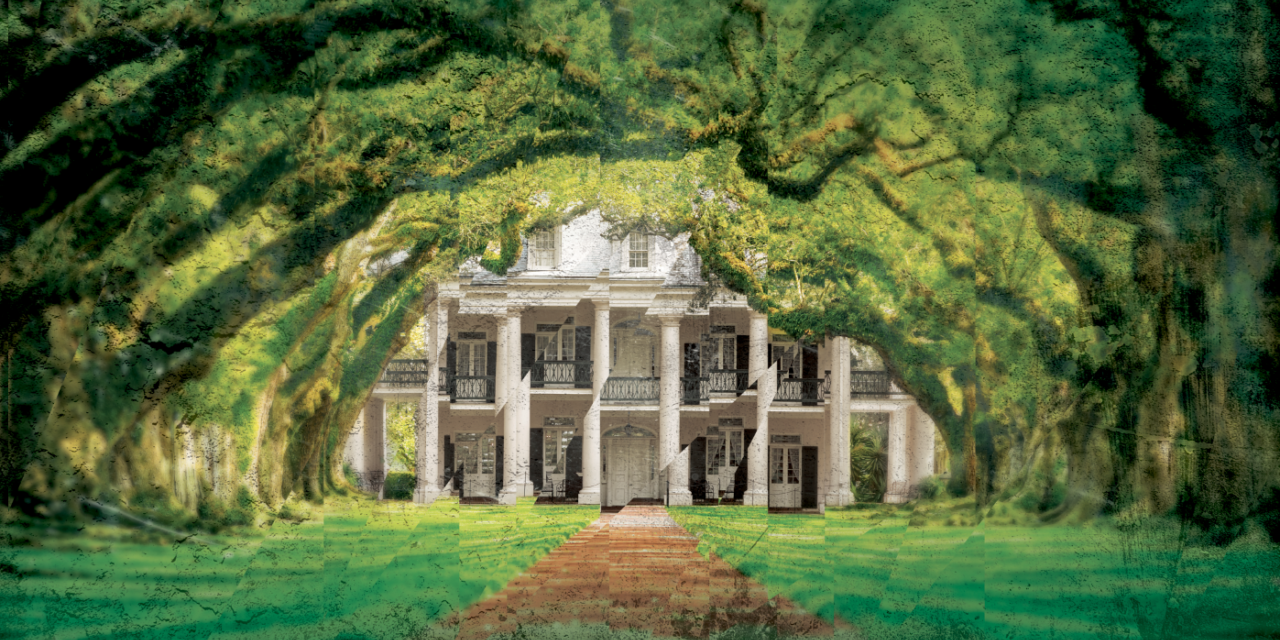

This is how Jeremy Harris’s Slave Play ends: in the very last scene, Keneisha, a black American woman who is no longer able to connect sexually and otherwise with Jim, her white British husband, screams the safe word “Starbucks” as he dutifully fulfills her own worst nightmare: being enslaved and raped by a white overseer at a Deep South plantation. Lacking a visceral understanding of the American racial psychodrama, the husband is at first reluctant to engage with Keneisha’s demands: in Act I, it is he who screams the safe word, halting the sex before climax: it is too brutal and too uncomfortable for him to assume the role of her oppressor (and to derive pleasure from it). Yet, by stopping, he is also in control, she reminds him. It is she who has to stop it. It is she who has to call out the safe word, regardless of his discomfort (sexual, emotional, and psychological). It is she who for once has to be in control of the situation, even if it’s staged. As audience members, we don’t know if by getting what she wanted, or what she thought she wanted, Keneisha is able to overcome her obsessive thoughts and disgust with her husband and his whiteness, which she can no longer separate from its historical stigma. We don’t know if they’re able to rebuild their relationship.

Is sex possible?

Starting with Simone de Beauvoir, who put forth this question first in The Second Sex, a number of feminist philosophers and theorists, as well as theatre and performance critics, including Andrea Dworkin, Monique Wittig, Judith Butler, Jill Dolan, Peggy Phelan, and Kathy O’Dell, have pondered this dreaded but also fundamental question: considering the unequal social, economic, and, more often than not, physical relationship between men and women, is it possible to have a heterosexual sex that’s somehow free from the gendered power dynamics of the real world? Is heteronormative sex possible? Or is it always tainted and reflective of the pre-existing power relations? For Dolan, the representation of heterosexuality as a political project is doomed to failure because “female spectators cannot be placed in positions of power that might allow for the objectification of male performers.” Since woman “can assume neither disengagement nor aesthetic distance from the image, she is denied the scopophilic pleasure of voyeurism [. . . ;] woman cannot hope to articulate her desire in the representational space,” Dolan argued (109). In her 1998 book, Contract with the Skin, Kathy O’Dell goes further, interrogating the very function of female masochism onstage (from Marina Abramovic to Gina Pane): the woman performing self-abjection is uncomfortable to watch as we question her intent, motivation, and purpose. Thus, such a project, O’Dell postulates, is also a political (and more often than not aesthetic) failure, as it is derivative of the male gaze. The masochistic meta-commentary on male violence nearly always collapses on itself.

In Slave Play, Jeremy Harris asks the same question, but about race: is interracial sex possible? Considering the baggage of American history (and the global postcolonial legacy), is interracial sex that’s freed from it possible? Harris is not the first to ask this. Black playwrights – Marita Bonner (The Purple Flower), Adrienne Kennedy (Funny House of a Negro, A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White), Amiri Baraka (Dutchman) – have asked it before in one form or another. Among Black intellectuals, most famously bell hooks, in her essay “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance,” argued that the taboo on interracial relationships has been foundational for the manufacturing of both power and desire. hooks draws on Michel Foucault’s ‘Repressive Hypothesis,’ in which he argues that pleasure and desire are a function of power. In other words, we create taboos and prohibitions to enhance “the pleasure that comes of exercising a power that questions, monitors, watches, spies, searches out, palpates, brings to light; and on the other hand, the pleasure that kindles at having to evade this power, free from it, foot it, or travesty it” (45). For hooks, the taboo on interracial sex has a similar function: it manufactures and maintains both power and desire. She implicitly asks, is interracial sex possible outside of that pre-existing historical racial framework? Is interracial desire possible outside of the racist structures that manufacture it? “The over-riding fear is” – she writes – “that cultural, ethnic, and racial differences will be continually commodified and offered up as new dishes to enhance the white palate – that the Other will be eaten, consumed, and forgotten. Acknowledging ways the desire for pleasure, and that includes erotic longings, informs our politics, our understanding of difference, we may know better how desire disrupts, subverts, and makes resistance possible” (380). Personal is political and vice versa.

In many ways, theatre and film fulfill the same fantasy role as sexual play: we use theatre to restructure our reality according to the new laws of power, the new rules of the game, in which we might no longer feel powerless. Maybe that is precisely why theatre itself has not been particularly interested in BDSM: as theatre people, we don’t like competition. There’s Genet, Schnitzler, Hare, and LaBute, but that’s about it. When women write about sex, power, and violence, they write (or perform) from the position of victims and in order to engage critically with the male-dominant discourse (or, occasionally, with ironic self-detachment, as in Dress Suits to Hire, for example). This is not surprising considering that much of Western theatre, art, and opera represent nonconsensual violence directed at women.

Like bell hooks, Harris asks about the political implications of sexual desire with respect to slavery and interracial relations in the U.S. In his book on Bosnia, David Rieff argues that sexual sadism is always a component of genocide: “There has never been a campaign of ethnic cleansing from which sexual sadism has gone missing.” Wars can be fought over resources, expansions, a misplaced sense of national dignity, but more often than not they are also about sex. In other words, genocides happen because they turn someone on, Rieff seems to suggest, or rather, mass conflicts provide cover for the sadistic impulses to find their outlet (Abu Ghraib is one such example). One can make an argument, Harris hints, that slavery happened because it provided a justification for unfettered and unconstrained sexual access to other people’s bodies: it was, foremost, a sexual perversion. Wars happen because they suspend all moral rules, allowing men to rape and torture with impunity (from Nanjing to Bosnia to Iraq). Sade, too, argued as much: every act of political violence has a sexual motive. Hence, in adapting de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom into Salo, Passollini placed it under the Nazi regime. (Although drawing a similar analogy in The Night Porter, Liliana Cavani had to fend off allegations of fetishizing fascism.) This is not a political or historical argument. It is an observation that mass violence is always interconnected with sexual violence. The question is whether or not the connection is intrinsic or incidental. What is the cause and what is the effect? What is the order of things?

Unfortunately, the fantasy is not a cure for the reality: no matter how many times one escapes one’s abasement in the contrived world of one’s bedroom, the reality outside of it stays the same. More so, just as the reality influences the fantasy, the fantasy always eventually slips into reality: hence, in Last Tango in Paris, once Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider leave their Paris apartment, he is no longer a mysterious and experienced older man initiating her into the previously unexplored realm of her sexuality, but a washed-up owner of a decrepit hotel, who must be killed to be gotten rid of: this is not the kind of man she wants to control her. Since the fantasy is not a cure for reality, it is never enough – and heightened, it always reaches its limits and leads to self-destruction. Keneisha gets what she wanted, but was it what she wanted? – Żizek would ask. Atέ, the line of perdition, the line of fantasy is not to be crossed…

Slave Play opens with the sexual fantasies of the antebellum South psychotherapy where the interracial couples replay the power relations of the Southern plantation. We know right away that this is a game, as they occasionally forget their lines or break their roles. The metatheatrical breaks in roles have a comic effect that suggests a kind of intrinsic silliness in trying to re-enact the Southern master/slave dialectic in modern times. Depending on what you think the role of comedy should be, the scene can be freeing (‘comedy allows for the reclamation of the discourse and agency of the oppressed’ ) or jarring (‘slavery was not a consensual game to laugh at with safe words and preplanned dialogue’). The tension between the two interpretations of the scene (and maybe even the play itself) can be felt in its dramaturgy: should we take the racial psychodrama seriously, or not? Is it a function (and foundation) of our current national sexual psyche, or merely a commodity maintained and managed by the army of therapists and whoever else makes a living from it?

This first scene is also a riff on a sketch from George C. Wolfe’s famous play The Colored Museum, in which Wolfe comments, sarcastically and without mercy, on white Hollywood’s preferred narratives that freeze the entirety of Black experience in trauma and its generational aftermath. From Roots to Twelve Years a Slave, white Hollywood has a history of rewarding and awarding the stories and representations of Black people as slaves. By re-enacting the scenes from the antebellum South with such casual attention to detail, and with metatheatrical disregard for narrative continuity, Harris’s characters expose their weariness of these narratives and their perversely voyeuristic appeal for white audiences: white America likes seeing and rewards stories and images of black subjugation. If you like this meta-commentary, you will think the play is clever in its self-indictment. If you don’t, you will think that hip meta-self-awareness is not a good-enough excuse for yet another commodified replication of this imagery. The question boils down to whether you think critical re-enactment of subjugation is a form of subjugation or not. Can a subaltern consent? – to paraphrase Gayatri Spivak.

Act II opens with a group couple therapy session that begins with a panoply of bromides familiar from morning TV shows, corporate retreats, and contemporary college campuses’ prepackaged diversity sessions. ‘Processing,’ ‘unpacking,’ ‘I hear you and I see you,’ ‘let us be together in space’ etc.– the clichés abound and are too familiar not to be funny – the scene mocks America’s narcissistic culture of self-exploration and self-improvement. The kind of first-world navel-gazing that’s often satirized in film and theatre, particularly in the context of current worldwide human rights abuses. (In Heather Raffo’s Nine Parts of Desire, a young girl living in bombarded Baghdad marvels at the ‘real problems’ of Oprah’s upper-class couch guests.) The time and expense involved in therapy already demarcate certain lines of privilege: disfranchised people more often than not cannot afford and have no time to dwell on their emotional problems, to paraphrase James Baldwin (“we can’t afford to care what happens to us”); they “can’t afford despair.” But the ‘therapy’ scene also mocks the oblique emptiness of the institutionally sanctioned language we currently use to discuss the issues of difference in polite, professional society (whether it pertains to racial, ethnic, or other otherness). It is a language of alienation, and not a language of human connection.

Eventually, the therapy ventures into an academic theory of race and sexuality, and we still don’t know whether it’s quasi-scientific psychobabble, or something profound that we should be paying attention to. The characters themselves don’t know. Some dutifully write down every word; others roll their eyes. The paid-for discomfort is palpable. Things unravel and get serious and seemingly real, and we are left with a dreadful feeling that the damage done by history is irreparable. You cannot escape the baggage of your people, no matter how hard you try, and you cannot understand the other whose body doesn’t carry the epigenetics of your ancestors’ trauma. This is not a particularly revelatory observation. Like sex, love might be also impossible. Can you love someone you don’t understand? But most importantly, can you be loved without being understood? Is understanding of the suffering of the other a prerequisite to love and care, and rights, and laws, and dignity? This is the trap of empathy, Paul Bloom argues: there are those you emphasize with and those you don’t, and that is the problem.

Why do we turn others into fetishized objects? Harris asks. Why do we turn ourselves into fetishized objects? Maybe because it is easier to be and to possess an object of one’s desire than it is to be and to possess a full, complex, contradictory, unpredictable other human existence. The fetish is hollow and it asks of nothing. It is not surprising that the play elicited such drastically different receptions – though it is mildly baffling why fifty years after Loving vs. Virginia, progressive white New York critics still seem to consider interracial sex (or gay interracial sex) “provoking” and “transgressive” or why the same progressive critics find mild marital S/M “daring” “raunchy” and “subversive” – a practice on daily display at NYC nightclubs. . . or most recently on Netflix – as mainstream an entertainment platform as you can get. bell hooks would probably argue that the language of the reviews – fetishistic and sensational but unintellectual – manufactures and maintains the taboo on interracial sex, and thus, manufactures the desire. Is the play then a meta-joke on white reviewers and white audiences…? Maybe. The mirror is there for a reason (though not a subtle and already explored theatrical device – most prominently in Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden, also a drama about politics and sadism).

Those who are well adjusted, who view sex as a source of bodily pleasure and intimacy, who prefer their history and martyrology sacred, and contextualized, will find Slave Play disturbing or perhaps even offensive. Those, on the other hand, who consider sex a human mystery to be explored, who can cope with their history and martyrology only at a safe, meta-ironic distance, will find the play layered enough to be worth their time and mental space. You might even find yourself holding both opinions – maybe even at the same time. There’s no way around it, and the play doesn’t explore or reconcile that discrepancy. On the other hand, therein might lie the rub with all sex theatre. The dramaturgical purpose of sex play is the climax, but the purpose of drama is catharsis . . . Unfortunately, more often than not the two are not congruent . . .

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Magda Romanska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.