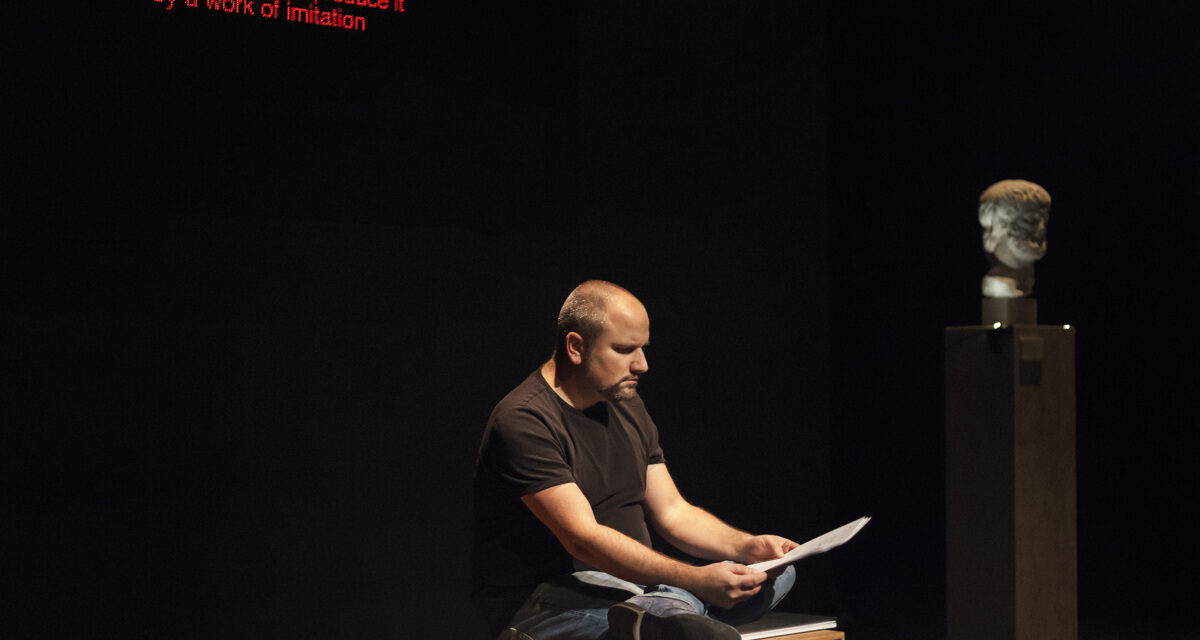

A bust of Aristotle stares out at the audience. A vaguely Romantic-style landscape depicting men riding horses next to snarling dogs hangs from the ceiling. I have no idea which exact painting it is but that hardly matters. It’s familiar, as if it were from any gallery in Europe. In amongst this miniature impression of a museum, Thomas Bellinck sits on one of those typical minimalist-style benches commonly found in museums. Bellinck is no stranger to these spaces, having already created a future museum to the former European Union in his previous work Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo (House of European History in Exile). This new work provides ample critique of the cultural institutions that uphold Europe’s problematic version of history.

In his introductory lecture, Bellinck delves into the myth of ‘Western civilization’ going back to Aristotle and his ideas about stories, philosophy, and politics. Stories help us understand the world but they are just that, stories. Not reality but a version of reality. And Aristotle’s version has disseminated the idea that there are those naturally predisposed to dominate and others to submit, leading to colonial and contemporary fortress-Europe, with its digitized borders and outsourced violence. It’s the Europe that plundered the world, put the loot into museums to be consumed by the public and upholds its own version of reality. History is written by the victor but what is history if not just another story? Bellinck’s engaging introduction provides us with plenty of provocations, priming us to critically consider our own assumptions as well as everything we see and hear in this fictitious museum.

Aware of his own privilege, he outlines his mission to fill this museum with the stories that can’t be told, that exist outside of fortress-Europe and the narrative it has built for itself. Leaving the stage, he allows disembodied voices from the borders of Europe to paint another picture of reality with their own words. Obviously, he has to leave. We don’t need another white, European guy literally and metaphorically taking up space to tell refugees’ stories for them. However, the form quickly becomes tiringly repetitive, as the various stories blend into one, a collage of people on the run, hunted down by border guards. Like a gallery replete with variations on a theme.

With each variation came the question: what happens when you put something in a museum? On the one hand, it becomes legitimized, a part of cultural history. On the other, it becomes a product to be consumed. When these untold stories are placed in this context they’re taken seriously but also commodified, subject to the same treatment as the ‘masterpieces’. Which is to say that the public only pays an average of 17 seconds of attention to a work or voice, before moving onto something else. Constantly on the hunt for something new.

Simple as ABC #3: The Wild Hunt may ostensibly be about the hunt for ‘illegals’ at the borders of Europe but its form redirects the issue back to the audience. One of the first recordings includes two displaced journalists’ accounts that while they do indeed hunt for ‘the truth’ they’ve also had to compromise and embellish that truth so that it’s palatable for the public. Thus we’re left to ask if we, the audience, are we hunting for true stories or just entertainment? By the end of the show, I’m not sure.

This article was originally posted on Etcetera on May 27 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Liam Rees.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.