In an age of so-called “cancel culture” it’s important to remember that for much of British history, it was the state, not the masses, who censored the work of artists.

Between 1737 and 1968 British theatre censorship laws required theatre managers to submit new plays intended for the professional stage to the Lord Chamberlain’s Office for examination and licensing. This was necessary under the Stage Licensing Act of 1737 and the Theatres Act of 1843.

In essence, this meant that the government collected, monitored, and frequently censored new dramas. In this way, the licensing of plays has inadvertently produced an extensive historical archive of surveillance and censorship. This includes records of early Black theatre-making, at a time when the British state did not routinely collect and preserve the work of Black playwrights.

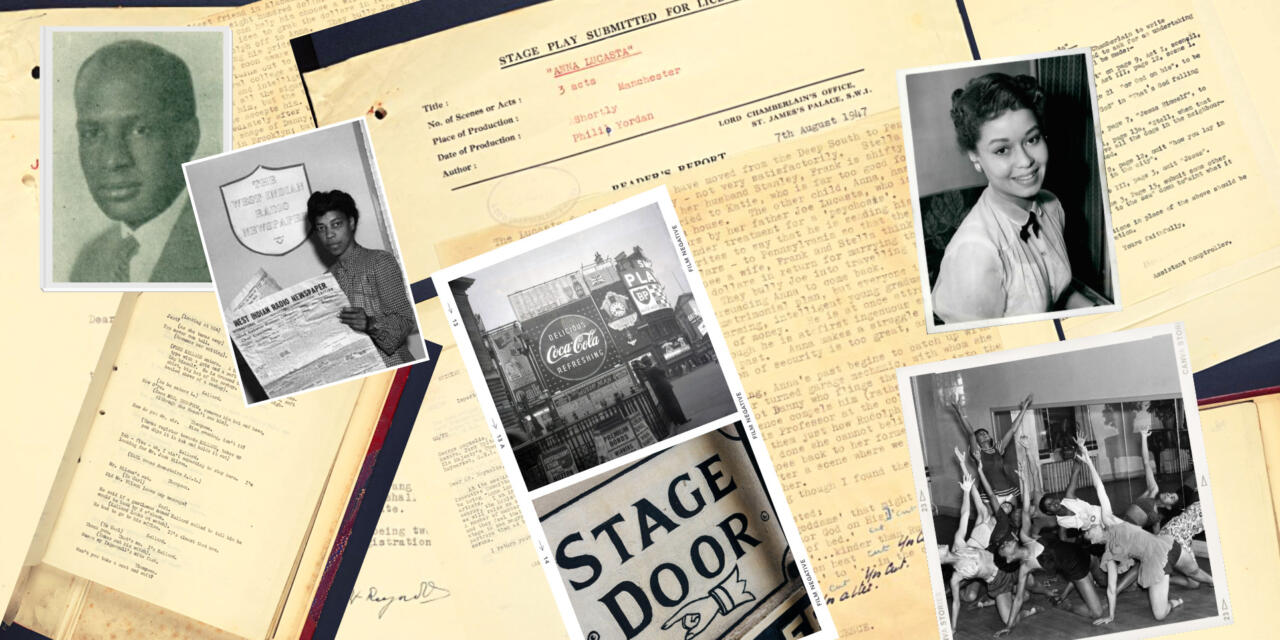

The Lord Chamberlain Play’s Collection, held at the British Library, contains theatre manuscripts as well as play readers’ reports and correspondence between theatre managers and the Lord Chamberlain’s officers which document the decision-making of the censor. While some plays were approved without a license, dramas containing blasphemous or obscene language and scenes of a sexual nature had the offending passages removed. Others were denied a license altogether.

The collection includes a number of plays by Black theatre makers that were well-known in their time but have since fallen into obscurity. These include At What a Price, written in 1932 by Una Marson, the BBC broadcaster, poet, playwright, and anti-racist activist who moved from Jamaica to London in the 1930s. The play explores women’s desires for love and for a career, as well as interracial relations, sexual harassment in the workplace and women’s friendships.

Lord Chamberlain’s correspondence file for the play Anna Lucasta

The archive also holds a copy of Appearances, a courtroom drama written in 1925 by African American entrepreneur Garland Anderson who set up a milkbar in London’s theatre district. The Broadway (1944) and West End (1947) hit, Anna Lucasta, was in the archive, too. The censors objected to the use of US swear words which had to be removed before Anna Lucasta could be licensed.

The play explores the possibilities of redemption for the “fallen woman”, Anna, a sex worker whose family renounced her only to lure her home in the hope of marrying her off to an honest young man with a bit of money.

It was originally written by a white American author and was rewritten by the American Negro Theatre with an all-Black cast. It ran for a year in the West End between 1947 and 1948.

The Film Version of Ana Lucasta

The archive comes to life

As part of a project looking at archives of surveillance, I worked with a group of theatre makers, researchers, and archivists to examine the plays. We wanted to find out what issues were important to Black theatre-makers and how they navigated white gatekeepers, including the censors and theatre managers who controlled the British theatre industry in the early 20th century.

Researchers and curators were able to identify and contextualize the plays, while theatre-makers considered what it would be like to stage these plays today. Would we reinstate lines censored by the Lord Chamberlain? Were there parts of the play directors might want to cut? And what to do with the censor’s reports – particularly those which contained racially offensive language?

Inspired by what we discovered, we created a performance of staged readings directed by Dermot Daly and Eleanor Manners. We used the manuscripts and censors’ reports on two plays by Black theatre-makers first staged in the West End nearly a century ago to bring them to life for a modern audience. We chose Una Marson’s At What a Price (1933) and In Dahomey (1903), one of the first musical comedies written almost entirely by Black theatre-makers and presented by Black performers in the US and Britain.

Separated by 30 years, and hailing from different parts of the African diaspora, these plays capture the diversity and excitement of Black performance culture in Britain in the early decades of the 20th century. But while our project opened up access to these theatre manuscripts, it clearly does not make up for the years of invisibility.

The power of encounter

In her recent biography of the Black playwright Lorraine Hansberry, Soyica Colbert, a professor of African American studies and performing arts, explains the importance of “encounter” for Hansberry both as a playwright and as a political activist.

Hansberry understood encounter as not simply an interaction between two individuals but a process in need of an audience: “A knowing or understanding look from a spectator,” she says, “disrupts the totalizing effect of another’s gaze,” and resists “racism’s power to isolate individuals”.

It is well understood that witnesses – or an audience – are central to theatrical work. But to witness and affirm is important to encounters with the archive too. Indeed, watching, hearing, reading, and performing these manuscripts together opened up new ways of using censorship archives.

These plays by Black theatre-makers as well as the censor’s reports are now free to view on the British Library’s Digital Manuscripts platform. It cannot right the state’s wrongdoing but reclaiming these neglected texts and creating opportunities for new encounters with them constitutes a form of redress.

This article was originally published by The Conversation on January 23rd, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kate Dossett.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.