“Research into ancient Greek music is pointless”—Giuseppe Verdi

“Nobody has ever made head or tail of ancient Greek music, and nobody ever will. That way madness lies”—Wilfred Perrett

At the root of all Western literature is ancient Greek poetry—Homer’s great epics, the passionate love poems of Sappho, the masterpieces of Greek tragedy and of comic theatre. Almost all of this poetry was or originally involved sung music, often with instrumental accompaniment. Scholars are now in a position to reconstruct from surviving documents how Greek music actually sounded. By combining this knowledge with modern analogies and imaginative musicianship we may make a start at understanding why it was thought to exert such extraordinary power.

Music was as central to Greek life as it is to ours. Greeks believed that music had the power to captivate and enchant. In the fifth century BC, the music of Athenian theatre was enjoyed by tens of thousands of listeners. Top performers were treated like pop stars: the piper Pronomos of Thebes was said, like Elvis himself, to have ‘delighted the audience with his facial expressions and the movements of his body’. The complex rhythms of Greek poetry are usually studied in terms of metre, but were also the basis of dance steps, which involved the rise and fall of dancers’ feet. Marks on stone and papyrus show how the beat fell in some cases of ancient rhythm, and help us to work out how the intricate rhythms may have been danced.

The principal components of Greek music—as of all music—were the voice, instruments, rhythms, and melodies. The instruments are well known from ancient paintings and surviving relics, some in excellent condition. Two main kinds of instrument, the double-pipe (aulos) and the lyre, were used to accompany song. The sweet sound of plucked strings allegedly empowered the minstrel Orpheus to entrance trees and subdue wild animals. Imagine that all we knew of the Beatles songs—or the operas of Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, and Britten—were the words. Then after two millennia, we had the means to rediscover what the music sounded like. We would be bound to recognize the huge difference the sound of music makes to the listeners’ minds and emotions. Imagine!

We know that music—singing, playing instruments, and dancing—was a significant part of ancient

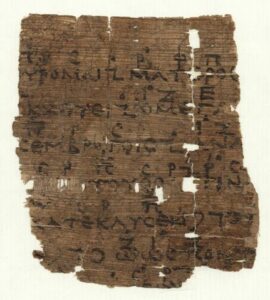

Image credit: The Euripides Orestes papyrus. Papyrus Collection, Austrian National Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Greek life, from the time of Homer in the 8th century BC for hundreds of years. It was used in religious worship, formal and informal entertainment and banquets, ceremonial occasions such as weddings and victory celebrations, and even in work settings where the aulos (double-pipe) was said to provide a rhythm for workers. Above all, however, we know that the surviving texts of most ancient poetry were sung to music.

Until recently, people thought we knew nothing of ancient tunes, but scholarship has now accurately deciphered marks on stone and papyrus that reveal songs and scraps of tunes, some of which haven’t been heard for 2000 years. The extraction of melody from the markings was allowed thanks to a comprehensive set of tables preserved from around the 5th century AD, by an otherwise unknown author called Alypius. Alypius listed the notations used to indicate vocal and instrumental melody, informing us what modes different marks could refer to and explaining the relative intervals.

A later author, the mathematician and astronomer Ptolemy, who also wrote about music in the 2nd century AD, gives us very precise details of the tuning of the seven- or eight-stringed lyres. He constructed an 8-stringed ‘octachord’ with moveable bridges and measured the proportions of the strings in order to specify their pitch. As a result, we are able to reconstruct stringed instruments and tune them exactly as they would have been tuned in his time.

Scraps of papyrus with musical notation began to appear as early as the 16th century, and Florentine musicians were excited to try and rediscover the music of ancient Greece. However, they found that the indications were too slight for them to make good sense of the music, and they went their own way in creating opera and oratorio.

Over the past few hundred years, however, more papyri have come to light, as well as stone inscriptions with large amounts of musical notation. From them, we are able to reconstruct the sounds of music that would have been sung and played. There are around two dozen melodies that have been transcribed and are able to be performed along with texts which provide the intrinsic rhythm—Greek words consisted of long and short syllables.

These pagan melodies, dating from the 5th century BC to the 3rd century AD, are audibly related to the sung music at the beginnings of the Western musical tradition as we know it, 9th-century Gregorian plainsong. The connection has never before been proven, and it changes musical history. A short film of the music was released in December 2017 and soon became a hit, going viral and reaching over 100,000 views in the first three months.

Now that we can reconstruct some of the sung versions of this poetry in musical form, we are bound to ask the question: how did ancient Greek music affect or interact with the texts of poetry?

Featured image credit: A 17th-century representation of the Greek muses Clio, Thalia and Euterpe playing a transverse flute, presumably the Greek photinx. Painting by Eustache Le Sueur. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Armand D'Angour.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.