This native Bostonian theatre production is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest-running play in the history of the USA. Shear Madness has everything: intrigue, humor, mystery, improvisation, friendship, incomparable stage chemistry, local cultural flavor, and even freshly gathered daily news. Shear Madness has been translated into 23 foreign languages; over 12.5 million people worldwide have joined in the fun.

In January 2020, Shear Madness celebrates its 40th Anniversary, while its various productions are playing in theatres all over the world. Despite its international fame, Shear Madness radiates with authenticity, rejuvenating energy, thanks to the impeccable work of its unique multigenerational ensemble. In this conversation with The Theatre Times, co-creators Bruce Jordan and Marilyn Abrams, as well as longtime Shear Madness actors Patrick Shea, Celeste Oliva, and Chandra Pieragostini shared their reflections on their experiences and memories of this friendship-fueled show.

Photo courtesy of Cranberry Productions, Inc. & Shear Madness.

Irina Yakubovskaya: What makes Shear Madness so unique that year after year, audiences all over the world come to see this show?

Marilyn Abrams: It is unique. It is interactive and immersive, and there was no such thing when it began [in the 1970s]. It was incredibly unique: when people came to the show, they discovered something they’ve never seen before. Today people know it is interactive, but it is still not like anything you’ve seen before. It is not like going to a theatre and seeing a play. This show reflects the events of the day on which it is performed.

Irina Yakubovskaya: The show revisits the events of every day and re-incorporates them in the core narrative/storyline, and by doing so keeps the show fresh and unique every night. Do you see this style as reminiscent of such an essential American art form as late-night TV entertainment and comedy shows?

Bruce Jordan: This is a very good comparison, but also this show combines two most popular theatre forms: “whodunit” with comedy and improv. The audience is the seventh character of the play, they have a say in how everything turns out.

Celeste Oliva: Everything on that stage is real and working. That is a real phone, we are really washing and drying hair, we have real coffee. In this small intimate space, it makes it very realistic. People have asked me “Are you a real hairdresser?”, and after all these years acting as one, I might be.

BJ: Marilyn, tell the story when you were in Philadelphia and a lady made an appointment with you.

MA: She did ask for an appointment. She then called the theatre and asked to cancel it.

BJ: A lot of improv the audiences don’t see because it happens in the dressing room before we come out on stage, which is a great fun part of the [actors’ backstage] experience. We’ll take two things that happened that day and we’ll discuss how to fit it into the show, what to do with it, how will it work. We usually give it three shots: the first time we try, the second time we’ll fiddle with it a little bit if it doesn’t work the third time – it’s out.

MA: Many years ago, Time magazine was here, and it was during the OJ [Simpson] trial. It was around 5 o’clock that afternoon, and they found the glove. Normally, a reviewer will never say anything to the actors after the show. That night, he actually stopped to see us and to say “I can’t believe the glove bit was in there.”

CO: For all of these reasons, this is why we are still here 40 years later. It is a play, but it is different every night because of the seventh character, the audience. Often, people want to come back to see what’s different from tonight to next week or next year.

BJ: It takes place at 155 Newbury street right here in Boston, all of the characters in the play are from somewhere in Boston, so there is a lot of Bostonian flavor to it.

MA: If it is snowing, the characters come in with an umbrella or soaking wet. We also have a radio station on, and it is, of course, a local station.

BJ: Word of mouth helps bring people to this play. The theatre people come early on, but the reason it’s successful is that they’ve told other people who then told other people who don’t usually go to the theatre. Even the sports husbands come, and they enjoy it. You can be fifteen and be there with your eighty-two-year-old grandmother, and both will enjoy it equally. It has an amazing universal appeal.

CO: A kid can ask a question, and the grandfather can ask a question, and they get the same attention. If they say something funny, we’ll bounce off of it.

Patrick Shea: If someone in the audience makes a laugh, it’s the best.

BJ: There are nights when we can tell if the audience is local or if they are from out of town. You won’t not like the show if you are visiting town, but if you are a local you get those little extra things.

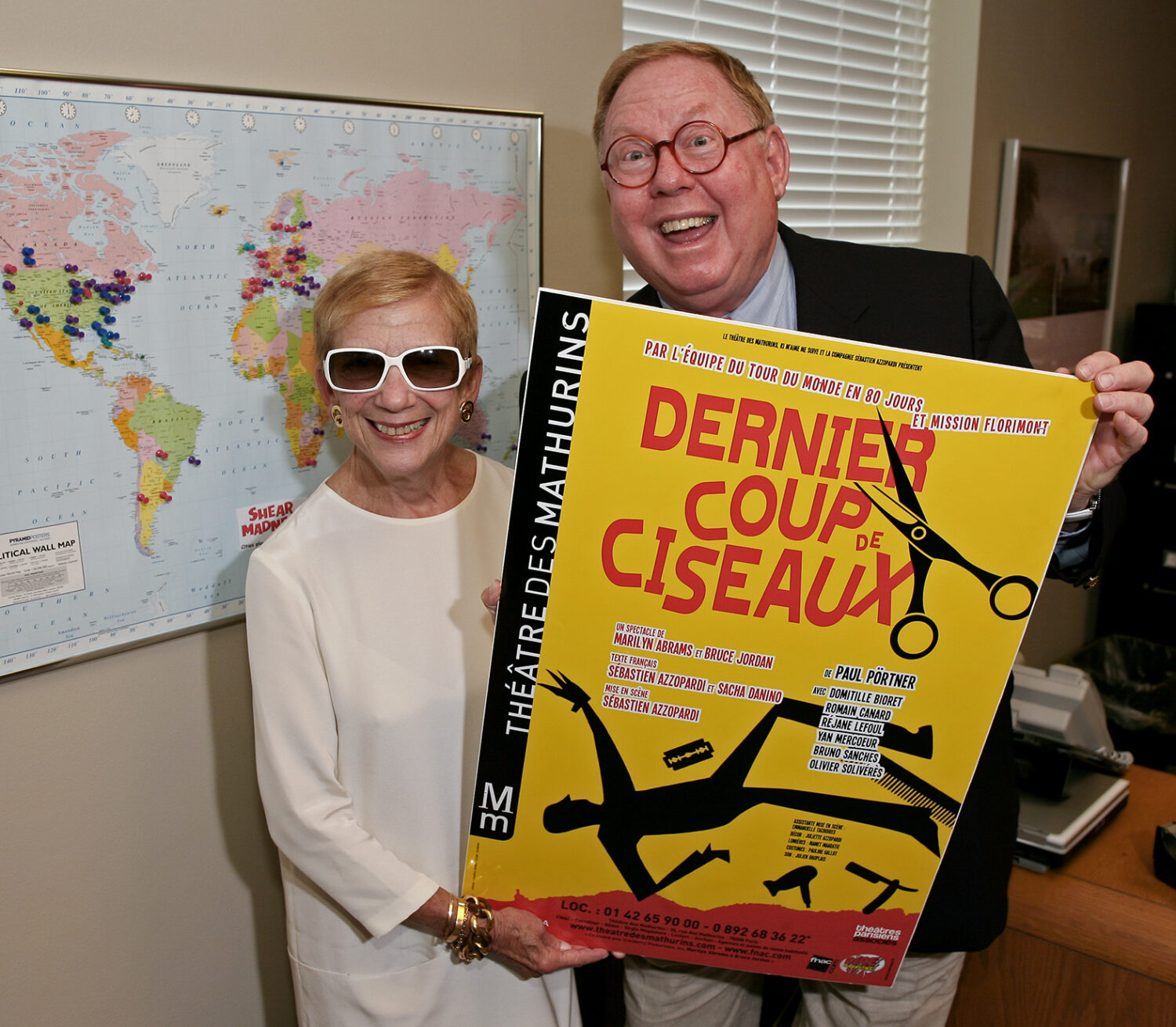

Photo courtesy of Cranberry Productions, Inc. & Shear Madness.

IY: The show was created in Boston. Do you think it would have been different if the show had been born elsewhere?

MA: My opinion is that it was good that we started in Boston, a theatre town, particularly at that time. I think we were able to establish our roots. We talked to every person who was out in public, we went out on our bicycles, we met every concierge, we were at every visitors’ booth, we could do that in this relatively small town. We brought people in a way in which they connected with others. I don’t think that we could have done that in New York City. You couldn’t get that local feeling that you had in Boston, even though it is a first-class city. There is a small neighborliness about it which helped us.

IY: In today’s global world, there seems to be a sense of nostalgia for that small-town ambiance.

BJ: When you play in towns like Rochester or Buffalo, NY, the laughs are so crazy. In Kansas City, they go nuts, because it’s just the locals. The local humor plays best in local audiences.

CO: In a New York production, it played a little less humorously…

MA: …and we have almost nothing of it in Washington DC. The jokes are not local but national.

CP: Here [in Boston] we have Beacon Hill, Southie, Revere, Newbury street, and you know exactly what they mean.

IY: Is there a place where the show hasn’t yet been performed, but you would like it to be there?

MA: We would like for it to reach China. There is interest, but it takes a long time.

BJ: It is in its 13th year in Seoul, South Korea. They had two very successful tours of France. They loved the local humor in Zagreb, Croatia.

CO: It is so important for you as a theatre person to feel seen, and heard, and represented on a stage. It is an incredible feeling. It’s like seeing your name in the paper.

BJ: There is a place in Rochester, NY, where they serve garbage plates. A garbage plate is made of macaroni, a whole hamburger, and a hot dog. We mentioned the name of the owner in one of the announcements that referenced local things, and locals fell on the floor [laughing].

Photo courtesy of Cranberry Productions, Inc. & Shear Madness.

IY: Does this always play in an intimate underground theatre space like the Charles Playhouse in Boston?

BJ: Unfortunately, no. Frequently, like in South America, we are in proscenium stage theatres. In New York, we played in a proscenium stage theatre, and we tried adapting it so it would be played out forward a little more. I always think it is better when the actors are on a lower level and the audience is raked.

MA: I’ve said this every time, but this [Charles Theatre] is the best theatre for Shear Madness.

CO: A couple of actors from New York have seen it here, and they said that it is such a different play when it is in this space. It allows you to be so real because everybody can see what you are doing.

CP: It is also easier to have a relationship with the audience.

BJ: When Marilyn and I moved the play to Philadelphia, it was on a four-foot-tall stage in a very ornate beautiful theatre of three hundred people. We had to adjust so much, vocally and physically. There were almost no laughs the first night because the audience wasn’t hearing us. This is the only theatre that has the entrances where they are, so when people go to other theatres it’s reversed.

Photo courtesy of Cranberry Productions, Inc. & Shear Madness.

PS: You’re not supposed to see someone come in a door, and invariably when the play was out in Los Angeles, I would be on the wrong side of the stage [by mistake].

BJ: Our first production outside of the US was in Barcelona, Spain. Then Barcelona had within 15 years just gotten rid of Franco, the dictator. The wonderful producers were very worried as they didn’t think the audiences were going to join in the way American audiences did. On opening night in a 600-seat theatre in a key moment in the play the whole place erupted in gasps and screams, the audience was so invested.

IY: Has there been any extraordinarily unique moments on stage that happened at some point over the years?

BJ: There is a moment in the show when the policeman character draws a gun. Following this scene, there is a blackout. One time, several armed men ran towards the stage after the blackout. Turned out they were bodyguards of a Saudi prince who was in the audience that night. They overreacted as they thought there was a threat to the Prince.

MA: That was unexpected, and that was not in the script.

CO: Without giving too much away… An actor can go down in the middle of the show. Then multiple things must shift. Often who you saw before the intermission might not be the same actors or characters.

IY: Do the audience members get confused?

PS: They love it. They love being part of the solution.

IY: What is the secret to your on and off-stage ensemble chemistry?

BJ: Hire the right people.

CP: Hire the people who are dedicated to the show and who love it. Some of us have worked together on and off for many years, we know each other very well and it’s very fun. It’s fun to play together on stage and it’s fun to have a new person come in and figure out how they are going to be part of it. We are also constantly editing the show, due to its flexible nature.

BJ: If a new person is not part of a working ensemble after 6 weeks of being in the show, it becomes a drag. It is not a very easy show to jump into.

CO: As an actor, you also have to have a heck a lot of endurance because when you have this many shows a week and a contract that is that long. You have to know that you can rely on other people to be working just as hard as you are, and that will show up all the time ready to go.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Irina Yakubovskaya.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.