INTRODUCTION

This article is comparative in approach and introduces the work of two classic post-war dramatists, Samuel Beckett and Tadeusz Różewicz. Both artists are usually perceived as leading representatives of the theatre of the absurd. It is discussed to what extent their work is really convergent, and to what extent the artistic means they use carry different meanings. One of the questions discussed is whether silence and speechlessness can relate to other experiences, when created, in the theatre, by these two playwrights?

SHORT BIOGRAPHIES

Samuel Beckett. Much to his surprise, Samuel Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969, “for his writing, which – in new forms for the novel and drama – in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation.” Born in 1906 in Dublin, he is a rare example of a bilingual writer – the majority of his mature works are in English and French language versions written by the author himself. He was descendant of the Huguenots, persecuted French Protestants, who found a home in Ireland in the 17th century. His Protestant background was of some relevance in a predominantly Roman Catholic Ireland, where he lived before he left the country for London and finally Paris. He published essays and narrative fiction in the 1930s, but the work that brought him international fame was written and published in the years after World War II. His most famous plays include: Waiting for Godot (En attendant Godot), Endgame (Fin de partie), and Happy Days (Oh, les beaux jours!). His later dramas are highly experimental, as can be observed in: Breath (it lasts less than one minute), Not I (the stage is covered in darkness but for the mouth of the speaker and the figure of a listener), and Ohio Impromptu (the action is reduced to reading the final pages of a long book). Beckett is also famous for his narrative experiments. These include his puzzling novels like Murphy and The Unnamable, as well as thought-provoking short-stories like “Lessness,” “Company,” and “Worstward Ho!”. He died in 1989 in Paris.

Tadeusz Różewicz was one of the key figures in Polish literary history after World War II. He was born in 1921 in Radomsko and he died in 2014 in Wrocław. His active engagement in the resistance movement during the war, and the experience of guerrilla life as a soldier of the underground Armia Krajowa (Polish Home Army), were formative for his bleak poetics. Skeptical about the communicative power of language in general and words in particular, he explored the expressive potential of subtext, ellipsis, and above all silence. In his poems and plays, Różewicz is far from creating heroic myths; on the contrary, he exposes the distressing ambiguities of a survivor. Poems such as “Ocalony” (“The Survivor”) and “Warkoczyk” (“The Pigtail”) are as canonical in the history of Polish, perhaps European, literature, as his play Kartoteka (The Card Index). For many years, he was associated with the monthly literary journal Odra, which is still published in Wrocław. Różewicz was fascinated with film and cinema, and he had considerable access to the secrets of the craft as his brother Stanisław was a leading Polish film director. Różewicz’s achievements were widely celebrated in 2021, with numerous theatre productions, exhibitions, publications, and other more or less formal cultural events in Wrocław and elsewhere. The Grotowski Institute was the main organizer of these events.

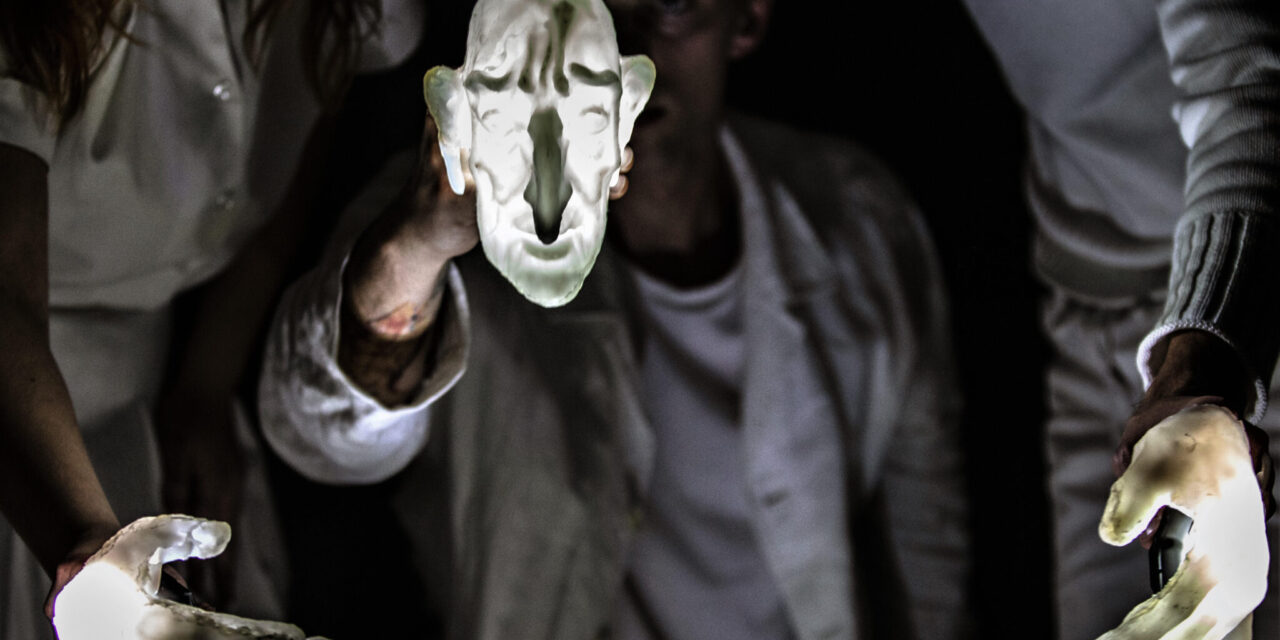

A photograph from the performance Caught (Złowione) which was part a series of events Archipelag Tadeusza Różewicza (Różewicz’s Archipelago). Photo by Tobiasz Papuczys | Instytut im. Jerzego Grotowskiego.

SHARED THEMES AND MOTIFS

There is much ground for comparative studies of the work of Beckett and Różewicz. Indeed, one may find many similarities in their attitude to language, their concepts of stage imagery, and their world-views. Both writers have usually been seen as representatives of the theatre of the absurd. The term was popularized in the 1960s by the scholar Martin Esslin to describe a group of European playwrights that challenged the conventional realism of the theatre. Useful as it initially was, the concept seems at present to obscure substantial differences between the playwrights. As a case in point, there is no doubt that Beckett and Różewicz shared a fascination with disintegration, skepticism, and detachment, but the experiences and meanings they attempt to convey are not always homogeneous. There is a great deal of resemblance, say, between Różewicz’s Hero from The Card Index and Beckett’s Victor Krap of Eleutheria, but their rejection of social bonds and aspirations is motivated by a different kind of experience of war-time atrocities in Poland and France. As Joanna Lisiewicz convincingly argues in her comparative study of the two playwrights, their exploration of the semantic capacity of silence and speechlessness is another feature shared by them. And yet, their silences resound with a the whole range of subtle meanings. The third point that may illustrate diversity in the apparently similar, is their preoccupation with garbage on stage. Różewicz’s play Stara kobieta wysiaduje (The Old Woman Is Hatching) (1968) presents an elderly lady in a restaurant that is physically being attacked by rubbish. Beckett’s shortest play Breath (1969) provides a glimpse on a stage totally covered by horizontal rubbish. Whereas the former develops an evolving metaphor in which life is increasingly bombarded with waste (words / futility / information), the latter echoes an old concept that life is a stage. It is frustrating that for Beckett the stage of life is covered with rubbish. Taking it all into account, one may conclude that there is still much interpretative potential for a comparative approach to Beckett and Różewicz. Biographical and aesthetic differences between them may be informative for contemplating diversity in parallel world-visions, especially at a time when a world covered by garbage has ceased to be merely a refined intellectual concept.

A photograph from the open-air performance In the net (W sieci) which was part a series of events Archipelag Tadeusza Różewicza (Różewicz’s Archipelago). Photo by Tobiasz Papuczys | Instytut im. Jerzego Grotowskiego.

***

The comparative approach to Samuel Beckett and Tadeusz Różewicz is further explored in a resource pack that is available here (https://between.org.pl/docs/education/2021/10/10_Beckett_Rozewicz_final.pdf) as part of the Between.Education 2021 program. Other artists discussed include Paula Meehan, Mimi Khalvati and David Constantine. (https://between.org.pl/education/2021)

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tomasz Wiśniewski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.