When reflecting on the experiences, and people, that have shaped us, certain individuals may emerge as recurring figures in our personal stories. More pointedly, when someone disappears and reappears throughout our lives, our connection to them may seem fated, even if the reason for their presence or absence is not always evident. “The Portrait of An Angel, A Lion, A Monster,” an original play by Katrin Arefy, explores this concept through the lens of one couple’s intermittent, decades-long journey of faith, longing, loss, and healing.

Rachael Richman. Photo: Thomas Hedges.

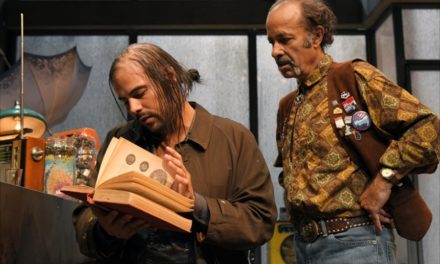

Set within its heroine’s mind and apartment, and subdivided into three consecutive acts, “Portrait” follows “She” (Rachael Richman), a writer recalling a shared history with her now-absent lover, a brilliant Russian-Jewish engineer (Isaac J. Conner, in pre-recorded video segments). Sorting through memories and notebooks, She reflects upon the forces that drew the pair together and apart throughout their relationship: their mutual battles with, and recovery from, cancer; a career that pushed him across the globe and into the path of political unrest; and prolonged periods of estrangement, longing, and reconnection with his family and each other. Despite her lover’s capacity for distance and callousness, and her struggle to reconcile the inconsistency of their partnership with the bond they shared, She paints him as an almost mythic presence, equally the specter haunting her, child she nurtured, and angel who carried her through joint and private struggles.

Like memory itself, faith forms a strong undercurrent to the piece’s journey, as much a source of connection as dissociation for its protagonists. The hope and comfort her lover found in prayer led the heroine to embrace Judaism; later, religion linked the couple once more as chance synagogue encounters spurred reunion after years of distance. Conversely, this same faith divided the pair, as struggles with outside prejudice and his family’s internalized anti-Semitism etched or widened the rifts between them. Attempting to make sense of their circumstances, She proclaims “I thought I could read God’s mind,” but admits that neither faith nor fate can offer any neat answers to their partnership’s ebb and flow.

Nima Dehghani’s video projections weave through “Portrait’s” narrative, a visual embodiment of the play’s emotional climate. Scrolling handwritten journal pages, Chagall-inspired animations, and speaking silhouettes leave winsome impressions as they capture the heroine’s efforts to pin down the intangible. Perhaps more pointedly, the projections form the means through which Connor makes rare direct appearances onstage. Accustomed as we become to encountering his character solely through another’s account, these appearances highlight the narrator’s bias, revealing her larger-than-life perception of an ordinary, if impactful, man. Likewise, the third act’s overlapping onstage-and-video dialogue, complete with vocalized stage directions, folds both voices into the narrative at a key point of turmoil and reconciliation.

Rachael Richman (onstage) and Isaac J. Conner (projection). Photo: Thomas Hedges.

As a memory play and extended monologue, “Portrait” draws more strength from ambience and character than active plot, but Richman’s nuanced performance gamely carries the show. That said, a bit more insight into the couple’s relationship woes and the specifics of why they parted would have lent greater clarity to a story we, like its heroine, must gradually piece together. Like a memory itself, “Portrait’s” story may blur, shift, and coalesce, but it is the piece’s emotional impact that resonates most clearly. While our search for meaning may yield no definitive answers, we need not know God’s mind to appreciate the mysteries and love that unite us.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emily Cordes.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.