American Buffalo is the story of a failure. A foretold, almost desired conclusion, an inescapable fate which one cannot possibly hope to avoid. It’s a tale of slums, slang, and profanity, of stinking shops and torn clothes. It’s an apology of decay: three human beings and an unlikely plan bound to fail, which they cling on to with their fingernails and refuse to let go of! It’s the desire for payback, for life, even at the cost of someone else’s.

—Marco D’Amore, director, actor and (partly) adapter for American Buffalo.

A play whose first nominal association could easily point to wild West myths of pioneers and Indians brought to Italy, translated into the Neapolitan dialect and led by Marco D’Amore, an actor best known for his role as the ruthless Camorra gangster Ciro Di Marzio in the prized TV serial Gomorra (third best international series for 2016, according to the New York Times): Could it possibly work?

Let us find out.

American Buffalo, by David Mamet (1975), to put it simply and in a largely simplistic fashion, is the story of three wretches trying to steal a rare coin. Not exactly an “American Buffalo,” as the high-sounding and (negatively) emblematic title goes, but rather a “Buffalo nickel:” something whose highest market price could barely exceed several thousand bucks. It’s no heist of the century; the prized reward could just as easily feel at home in a pawn shop. And yet, the characters struggle to achieve their unlikely goal as if their lives depended on it; as if putting their hands on that tiny, round piece of copper meant wealth, glory, redemption in front of a society which has confined them to its edges.

Donny “Don” Dubrow, the junk store owner who was “robbed” of the coin in the first place at a price which he now considers too low, his inept gofer Bobby, and the pretentious know-it-all Walter “Teach” Cole: three characters who are inevitably bound to fail, whose desperate attempts to succeed are both immediately funny and intimately disturbing, leaving them unable to emerge from the muddled pool of their low human condition.

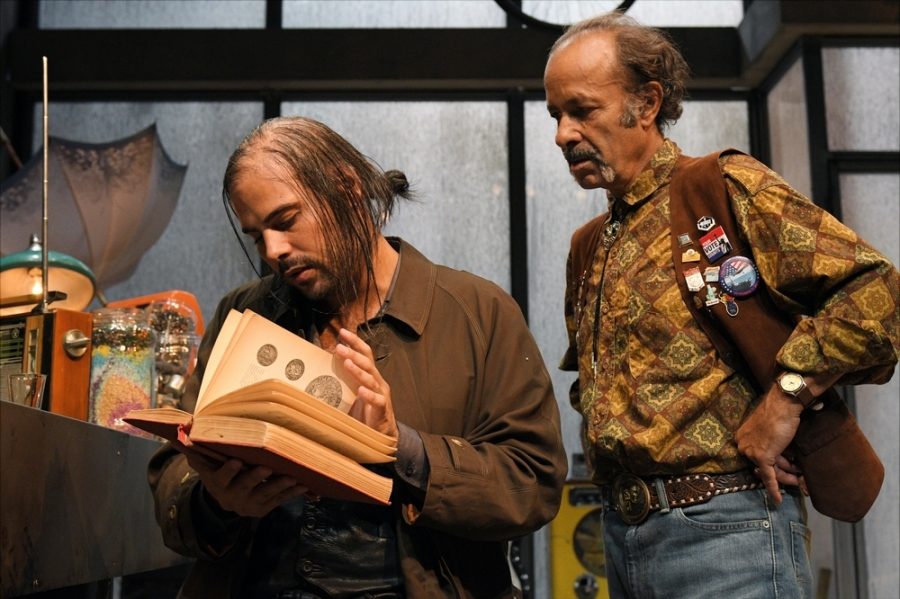

Tonino Taiuti and Marco D’Amore. Photo Credit: Bepi Caroli

The Italian adaptation as staged in Milan (Teatro Franco Parenti) was available to viewers in early December 2017, from December 5-10, as part of a national tour spanning most of the Italian peninsula (Rome, Naples, Latina, Pescara, Orvieto, Turin, Milan itself and Pistoia, among others). The play takes place on a stage not unlike that of its American cousin from 2010 (Steppenwolf Theatre, Chicago). It is a puteca, the Neapolitan equivalent of a humble junk store, crammed full of unwanted objects, with piles of abandoned things reaching up to the ceiling and framing the shop window that acts as the stage’s actual background: and indeed, as the characters’ only way of relating to the outside world, clouded in darkness even during the play’s “daytime.” The scene is no less than impressive, with each and every detail concurring to grant it a unique, seasoned feeling; dominated by pale, brown and yellowish tints standing out against the empty turquoise of the window.

It’s a world where the only sign of vivid color comes in the form of the American flag, a clear nod to the original as much as a mark of its owner’s delusive passion: that for the Country of Opportunity, for a purely immaterial world of stars and stripes as idolized by postwar Italy. Donato “Don” (Tonino Taiuti), [1] the shop owner and the “mastermind” behind the criminal plan hatching between its walls, strolls around the scene in cowboy boots, cropped jeans, a leather vest laden with brooches, and a bolo tie around his neck, showcasing his farcical obsession while mixing clumsily pronounced English terms in a Neapolitan dialect and a largely Neapolitan outlook on life. His character might as well be built around the recurring song Tu Vuò Fà L’americano (roughly You Wanna Be The American), by Renato Carosone, which would not feel out of place as Don’s personal theme music: this in spite of his flaunted love for rock ‘n’ roll, that is. At Don’s side is Robbé (Vincenzo Nemolato), [2] a good-hearted but not exceptionally bright aide constantly struggling with an unexplored problem (drug addiction, most likely), and the unwitting pawn in Don’s plot, the one meant to do the dirty work while gaining a meager fraction of the prized coin’s worth.

Vincenzo Nemolato (left) alongside Marco D’Amore. Photo Credit: Bepi Caroli

Theirs is an unlikely duo, one which could hardly achieve anything on its own. It is too bad, then, that the third member of the aspiring party of professional thieves is just as bad, if not worse. O’ Professore, [3] D’Amore’s character, looks nothing like his leading role from Gomorra: the silent, no-nonsense gangster of few, monolithic words makes way for a sad, bumbling fool, no more pretentious than he is pathetic. A broken man incapable of stopping his stuttering motor-mouth, clad in fancy clothes eaten away by time and wear, and with his usually clean-shaven head topped by greasy, sparse strands of messy hair. He is completely unrecognizable: a testament to his actual acting skills, putting some needed distance between a most iconic face and the role he is stereotypically associated with. [4]

Don, Robbé, O’ Professó: [5] the three wretches from the original, transported to a Naples of lowly plans, small Euro sums, and colorful language. Indeed, the dialect itself might be considered the play’s main character, the true object of its synopsis: flowing from the characters’ mouths like an uncontrollable tide, bouncing back and forth between them (a successful mirror of Mamet’s signature style, courtesy of adapter Maurizio De Giovanni, as much as D’Amore’s) as the plot unfolds, gets more and more complicated, clashes with its characters’ inability to live up to it. An unlikely team of losers trying their hand at what they perceive as the “hit of all hits,” fancying themselves seasoned gangsters but stuck in a routine of waiting and indecision, experiencing overly tense calm before a storm which might never come: unwilling to take action until the arrival of the famed “poker ace” Sasá, [6] a Godot-like deus ex machina acting as the container of all their delusions.

Entertaining, funny, hilarious, and all the while completely lost. A bunch of misfits which only a cast of exceedingly capable actors could have brought so vividly to their desolate lives made to move before an astonishingly appropriate scenography and with the thick blood of a visceral and musical language coursing through their veins, giving substance and shape to their words.

So, to answer that question: Yes. It does work.

Vincenzo Nemolato. Photo Credit: Bepi Caroli

Notes

- And “Don,” aside from remaining faithful to Mamet’s work, is an honorific form common to Southern Italy, where it precedes given names as a sign of respect; a custom sometimes distorted by mafioso usage (most evident with fictional characters such as TheGodfather’s Don Vito Corleone).

- “Robbé” is to “Roberto” what “Bobby” is to “Robert.”

- “The Teacher,” as a nod to Mamet’s “Teach:” and bearing a no less sarcastic connotation.

- It’s worth noting that, while largely known for his TV role, D’Amore has worked with some of Italy’s greatest theatre personalities: Elena Bucci and Toni Servillo (the main character from Paolo Sorrentino’s Oscar-winning The Great Beauty) among them.

- As colloquial Neapolitan would have it.

- “Fletcher,” in the original; “Sasá” is an affectionate diminutive for “Salvatore.”

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Davide Cioffrese.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.