Theatre as a memory vessel is nothing new to contemporary theatre. There is a reason why types of theatre like documentary theatre, heritage theatre, and reminiscent theatre are developed around two to three decades ago when practitioners recognized that theatre can connect to people with real-life events presented by real ordinary people.

Through the short period of applied theatre development, these types of theatre have escalated their level of production value. They are not only about presenting interview transcripts in verbatim but highly emphasizing on the scenography which inflicts emotion to the audience. ‘Acting’ becomes more and more challenging as to not letting the audience to think that what is presented is not genuine or trustworthy. After all, theatre is a medium for collective emotional release, which means it requires universal recognition of human nature.

That is why 887, Robert Lepage’s solo act recently ran at the Lyric Theatre of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts as one of the important highlights of the 47th Hong Kong Arts Festival, is a rare but also important production if one sees it as reminiscent theatre. It is because Lepage is no doubt already a legend in the theatre world, a renowned theatre practitioner who this time tackles his own personal experience during his childhood. As an actor and director, would Lepage be lucid enough to be ‘trustworthy’ about his past when he is such an auteur in theatre?

The result is a triumph, but with a bit of coldness due to some of Lepage’s own fantasy that requires knowledge on the context of the piece.

First of all, sticking back to the Festival’s theme this year, ‘At Every Stage,’ 887 proves that the theatre space is a place for ’emotional reality’ (a term coined by Belgian designer Jan Versweyveld) even though Lepage replicates his memories with vivid details. The title 887 is referring to Lepage’s first address with his family, 887 Murray Avenue in Québec City. One would think that Lepage is going to tell us his own personal family life or anything that is domestic. This is only part of the show. With an introduction by Lepage stating out his artistic statement on why he created 887 at the beginning of the show, we know that the piece is about how people choose to remember things, and why Lepage will choose to remember his childhood in details while he is struggling to remember an important piece of poetry to most Québec locals which he needs to present it later.

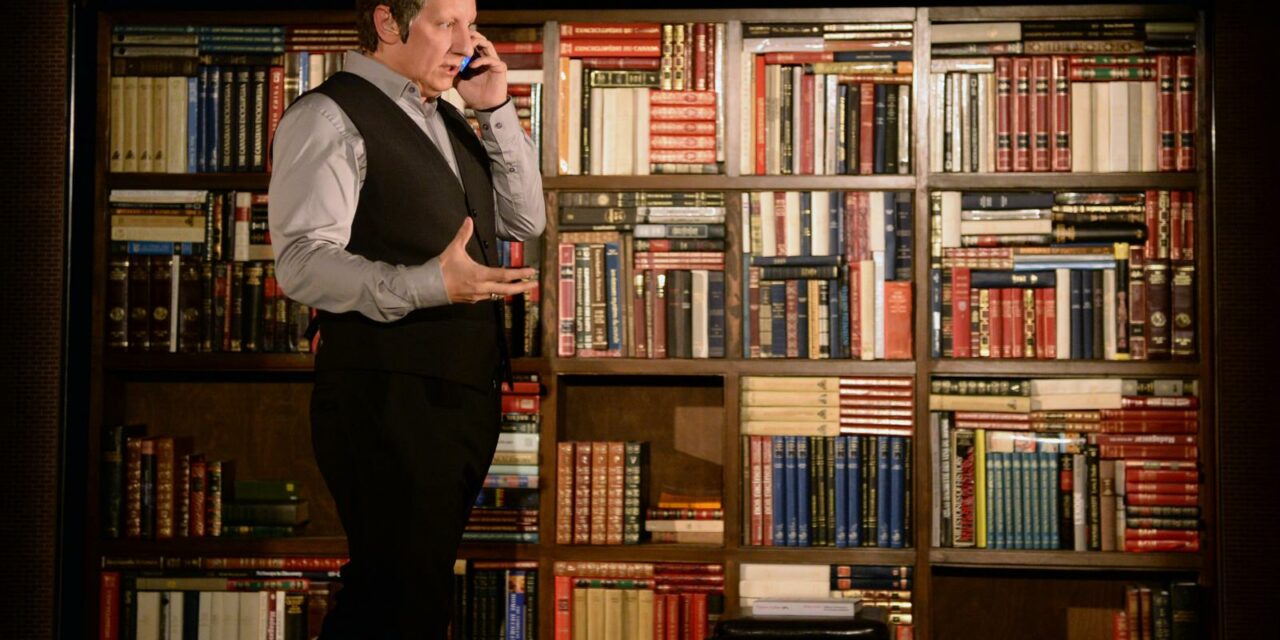

Robert Lepage in 887. Photo Credit: Érick Labbé

The answer is yet to come, but Lepage’s own eccentric charisma as a performer is strong enough to lure the audience to listen and follow his journey down on memory lane, not to mention his inventive scenography that always keeps the audience to engage. This time, Lepage creates a rotated dollhouse on stage that replicates his old home. One cannot praise enough for the details and delicacy of the construction of the dollhouse. Yet, there is always magic within Lepage’s set, and the transitions between scenes with the dollhouse develop the whole 2-hour show into a smooth flowy dream sequence.

However, in between the reminiscences, there is always reality. Occasionally, Lepage (as Lepage) will act out a scene of him talking to one of his acquaintances at his current home, having long conversations in Canadian-French about his struggle of not remembering the poem. Comparing to the absolutely imaginative scenes dealing with his childhood, these scenes of ‘kitchen-sink’ drama really informs the audience a deeper layer on why nostalgia is heavy and will produce an emotional release.

With an elaborate kitchen set full of naturalistic elements, Lepage acts out these scenes with obvious alter ego (though never overacted) that gives the audience an alienated cold read on Lepage’s life as an artist. He is a renowned theatre director who has been invited to present a poem that locals are very familiar with, yet he cannot get through the fact that he has trouble memorizing his lines.

Lepage clearly mirrors this situation to the nature of performing arts, the very medium that requires memory. During these scenes, even though the objective for Lepage is to memorize the poem, he never gets to the core of it. In returns, he talks about his identity crisis within the artistic field. He longs for recognition by the masses, yet, according to Lepage, constantly fails. These long vignettes tie in with the aspect of how Lepage’s memory presented inflicts who he is now, a grumpy cynical theatre artist. They also inform the audience why Lepage keeps going back to his past and keeps doing theatre because he has to search for his identity. The impact on reacting to Lepage’s reminiscences is much stronger and deeper.

Home is a key topic to explore in 887. The main dollhouse represents Lepage’s home in several stages: his first one (the residential building), his current one (as a kitchen) and a screen on one side showing his origins through projections. Apart from the revolving main set, model-like sceneries with miniatures representing Lepage’s relatives and neighbors and props enter and exit laterally and automatically to give an illusional of a world that objects run by their own. Those models and mini-figures are spectacular to watch, especially when multi-media is involved to give the audience a duo-perspective on the passage of real-time.

Robert Lepage in 887. Photo Credit: Érick Labbé

However, what I get from the production is that Lepage is immensely political. The term ‘Home,’ to Lepage in my opinion, is the memory place that defines oneself, and he never hides the truth that his memory is constantly wrapped up with political situations. From the establishment of FLQ (Front de libération du Québec) to the controversial “Vive le Québec libre!’ speech by Charles de Gaulle in 1967 to the October Crisis in 1970, Lepage constantly feels sarcastically melancholy about his past. Even for theatre, a place where he thought he finally could recede for happiness does not go smoothly due to politics. One can sense the ‘wounds’ Lepage has suffered, and his ‘scars’ are delivered these rightfully to his audience, a long, steady, depressive status.

It is this type of lucid presentation by Lepage yet never settle for comfort in his reminiscences that gradually sparks grudge and anger. In the end, Lepage, standing alone in front of the audience, recites the poem. The poem is called ‘Speak White’, a very famous political poem written by French-speaking Québecer Michèle Lalonde that vividly opposes the imperialism of economy and culture dominating the working-class in Québec. It is a poem that directly accuses the domination of the English language and why this poem has to be written and recited in Canadian-French.

It is a joy to see Lepage showing his professionalism in reciting the whole long poem with skills and passion. The fire and determination exude from him make this moment enticing an ovation. It is also the structure Lepage has created throughout the whole piece that up to this point, the audience finally can feel the weight of this poem, the reason why such piece of literature should be remembered by at least all Québecers since it is part of the place’s history, the memory of ‘home.’ We also can (sort of) finally get the answer to why Lepage cannot remember the poem. It hugely suggests that Lepage has deep-emotional linkage with the subject and context of the poem that blocks Lepage’s comfort of getting close to it. We share Lepage’s frustration of not remembering it, and the real reason might have a thousand possibilities, but we as the audience do not need to know. After all, the theatre acts just like a memory palace, and we only need to remember the moment without losing sight that it is the emotions we connect with what we see that defines us. That is enough already.

887 at Lyric Theatre, The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts

An Ex Machina Production

A 47th Hong Kong Arts Festival Presentation

Closed on 2nd March 2019

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Clement Lee.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.