Rising has just completed its second run across Melbourne. The newest addition to the city’s festival scene, Rising replaced the much-loved White Night festival and the much-celebrated Melbourne International Arts Festival.

As a new major arts event for a city that has a year-long calendar of significant festival activity, Rising has yet to establish what kind of intervention it is making in our cultural conversation – although its slick marketing line, “Music, Food, Art and Culture under Moonlight”, speaks to the notion of Melbourne as a wintry ethereal nighttime stage.

Led by artistic directors Hannah Fox and Gideon Obarzanek, Rising 2023 was an eclectic mix of local and international work. Some offered spectacle and thrill (Tanz and Euphoria) and some offered participation and community (The Rink and 1000 Kazoos).

But I found the highlight of Rising to be the significant and thrilling work created by First Nations artists across dance, visual art, theatre and music.

A key part of the journey of seeing work at Rising was the act of embodied witnessing.

My top three works situated witnessing as a political act. Witnessing is an act of deep listening, designed to change and shift your perspective. These works invite you to revisit what you thought you knew.

Each functioned to rethink questions of history and philosophy, to reshape notions of culture and memory, and troubled legacies of colonial violence.

Jacky

Jacky, a new play by Arrernte playwright Declan Furber Gillick, is a beautifully nuanced and performed investigation of the weight of white expectation and capitalism and its potentially dangerous impact on First Nations people.

Jacky (Guy Simon) is a young man who has moved from his community to the city with aspirations of securing a white-collar permanent job and owning an apartment. Jacky’s younger brother, Keith (Ngali Shaw), is sent by family to join him and soon upturns the ordered trajectory of Jacky’s life.

What quickly emerges is a profoundly uncomfortable look at what constitutes palatable Aboriginal behaviour by white people.

Alison Whyte (left) and Guy Simon (right) in Jacky. Photo by Pia Johnson/Melbourne Theatre Company.

Jacky’s well-intentioned white boss (Alison Whyte) engages in culturally incompetent behaviour when she requests Jacky pretend he is from a local family group. Jacky’s sex work client, Glen (Greg Stone), requests that Jacky participate in an act of racist role-play.

Keith challenges the social expectations of “good Aboriginal” Jacky has been relying on. He plays witness to the bind Jacky finds himself in: whether he succumbs to the demands of white expectation, or forfeits the social and material gains that are part of playing the role of “sexy Black poster boy”.

Jacky is part of the Melbourne Theatre Company’s season, playing at Arts Centre Melbourne. For me as a white audience member, the performance lays bare an act of political witnessing as Furber Gillick’s writing demands you pay attention and not look away.

Titled in reference to Jacky Jacky, an Aboriginal guide who was awarded medals for his service to NSW, the play troubles ideas of subservience and collaboration within white and First Nations relationships.

It reveals the racist and white supremacist underpinnings of ideas of Aboriginal inclusion premised upon white understandings of success in a capitalist system.

Shadow Spirit

The exhibition Shadow Spirit brings together 30 contemporary First Peoples artists and collectives from across the country into an immersive exhibition, including 14 specially commissioned works.

Curated by Kimberley Moulton, Shadow Spirit weaves throughout the decaying and compelling site of the rooms above Flinders Street Station. Works incorporate a range of forms including light, sound, sculpture, screen and projection.

Ambitious and stunning, as you wander through the exhibition works pay tribute to AC/DC; speak to contemporary hero narratives; and feature First Nations Jedi Knight figures blinking back at you on full-size screens under expansive celestial skies.

There is a giant sculptural bandicoot spirit animal; works that map the spirits and energies of Country, waterways and skies and speak to how ancient knowledges protect land and children; and works that directly address the space between what is known and tangible, and what is felt and intuited.

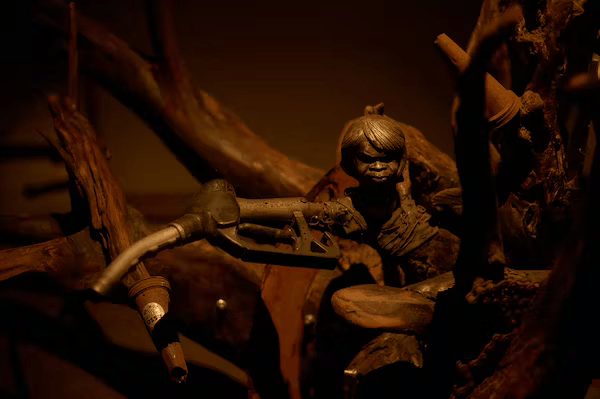

Deeply Rooted, by Karla Dickens. Photo by Eugene Hyland/Rising.

One stand-out moment is Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens’ sculptural works Deeply Rooted.

These spiky works fuse together native hardwood from the artist’s Country with found objects like witches hats, steel caps, broken pieces of rabbit trap, petrol nozzles with the sculptural doll-like head of an Aboriginal child.

Together, these objects create a monstrous and confronting homage to colonial violence and destruction, and a comment on the failure of successive governments to implement meaningful policy change.

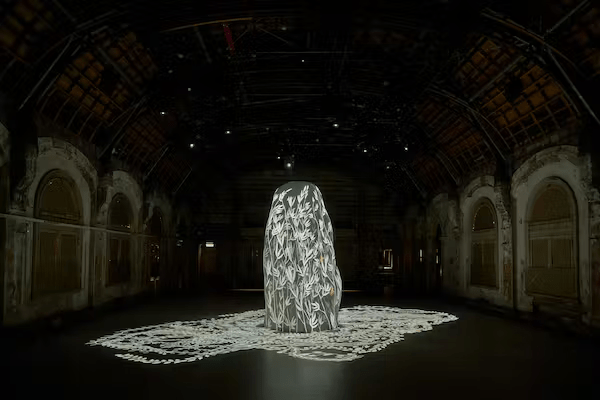

Another stunning moment is Rarrirarri in the large ballroom.

Artistic collective The Mulka Project and Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda (Yolŋu) have collaborated on an installation. A stone monolith (part Uluru and Kata Tjutu and part termite mound) rises from the centre of the room. Across this screens stunning graphic projections of floral and animal landscapes.

Rarrirarri by The Mulka Project Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda (Yolŋu). Photo by Eugene Hyland/Rising.

Rarrirarri speaks clearly to desert landscapes and ceremonial and spiritual Country. It requires you to sit and watch it for some time, as the experience of passing time and a landscape of seasonal change reveals itself in the stunning moving graphics of the art work.

The exhibition’s location at the Flinders Street ballroom brings these stories of creation, ancestral knowledge, spirituality and the legacies of colonial violence into conversation with the city’s civic centre. This site is full of cultural memory as a meeting place for railway workers for over 100 years, and its deeper history as a Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung gathering place across thousands of generations.

Shadow Spirit invites you to linger, to witness and absorb the breadth and depth of knowledge and culture and story threaded through each room in the space.

You are asked to consider your own position and history in relation to these stories, and how you connect and belong within the ancient and contemporary narratives running through the exhibition.

It is a gift to Naarm: a physical and spiritual centre for reflection and communion and gathering, a showcase of the excellence of our First Nations artists and a demonstration of art itself as a political witness.

Tracker

A co-production between Australian Dance Theatre and Ilbijerri Theatre, Tracker is a remarkable piece of storytelling about Wiradjuri elder Alec “Tracker” Riley.

Riley worked with the NSW police for over 40 years solving crimes to great acclaim. He was the great, great uncle of director-choreographer Daniel Riley.

Blending contemporary dance, text, live music and a simple but effective 270-degree rotating set design of scenic painted curtains and greenery rigged around a circular ring, Tracker takes us deep into ancestral Country in the middle of the night.

Our protagonist (Ella Ferris) has travelled to reconnect with the spirit of her great great uncle prior to giving birth to her own child.

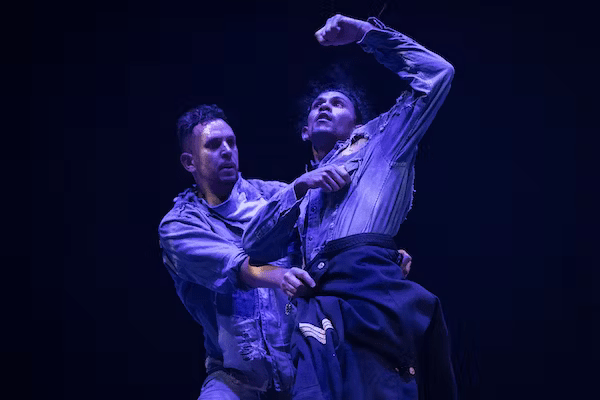

Kaine Sultan-Babij and Tyrel Dulvarie in Tracker. Photo by Pedro Greig/Rising.

She seeks to understand and uncover this piece of her past in order to keep her son safe. In doing so, she reveals how our access to the truths of these stories of cultural resilience are obscured and hidden by layers of history and colonialism.

As the remarkable stories of Tracker Riley’s success in finding missing children and bringing criminals to justice are revealed, three spirit guides appear (Tyrel Dulvarie, Rika Hamaguchi and Kaine Sultan-Babij). Their poetic and synergistic movements echo, enhance and articulate the searching nature of the story.

As the audience, we bear witness to this uncovering of a piece of our nation’s past. Throughout the work, we seek to understand how this extraordinary man successfully forged a path between ancient wisdom and colonial structures – yet received no pension at the time of his retirement.

This is a powerful and ambitious story, asking us to look more closely at history and what the past can reveal about today.

Jacky is at Arts Centre Melbourne until June 24. Shadow Spirit is at Flinders Street Station until July 30.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sarah Austin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.