Vancouver, British Columbia

Carla Chambers-Jeffreysreviews Dark Glass Theatre’s production of Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Ruined at Vancouver’s Pacific Theatre:

Ruined by playwright Lynn Nottage shows the colonial inheritance of social decay instituted by European-style capitalism and patriarchy. This history continues to drive immigration and economic policy in Western countries; at its core, however, Ruined addresses the patriarchal violence that, as one character poignantly says, takes place “on women’s bodies.” Set in the contemporary Democratic Republic of Congo, the bodies at the center of this story are those of Salima, Sophie, Josephine, and Mama Nadi. Their status as women “ruined” by rape, in most cases gang rape, makes them rejects from respectable society. Thus, they are forced into sex work in Mama Nadi’s tavern-brothel.

Shayna Jones, CJ Jackman Zigante, and Makambe A. Simamba in Ruined. Photo by Emily Cooper.

In this production by Vancouver-based Dark Glass Theatre, Shayna Jones gives a powerful performance as Salima, a woman whose peaceful family life is destroyed when the ongoing civil war brings death and sexual violence literally to her doorstep. Jones’ complex performance conveys Salima’s mournfulness, tragedy, and betrayal while alluding to an indomitable resolve that demands she find justice that honors herself before all others.

All of the female characters carry this strength in their unique ways. Makambe K. Simamba is endearing as Sophie, a young woman maimed by her attackers. Simamba convincingly conveys a quiet fragility in her evocation of Sophie. Simamba’s portrayal demonstrates how Sophie must use meekness to hide her cunning intelligence, a dangerous trait in the misogynistic environment in which she is subject. The paradoxical Josephine (Rachel Mutumbo) fiercely embodies the grey areas that form out of feminine sexual expression within the confines of sexual oppression. In Josephine, Mutumbo gives a nuanced performance that organically exposes vulnerability behind Josephine’s brashness.

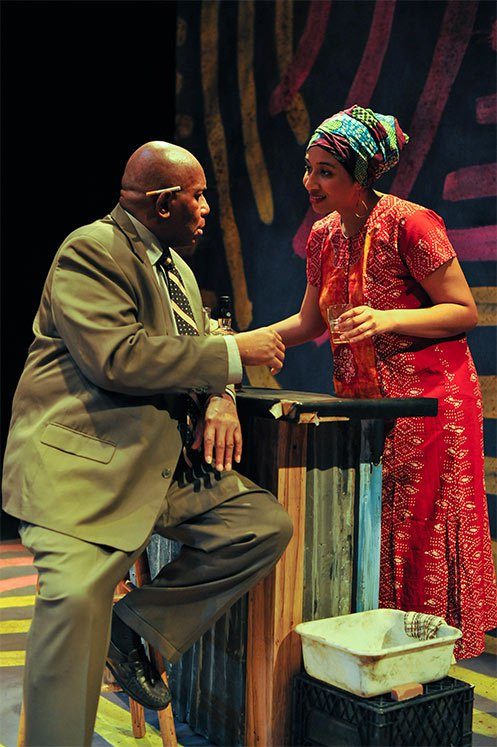

Tom Pickett and Mariam Barry in Ruined. Photo by Jalen Saip.

Amidst the scarcity of supplies brought about by war, Christian is a local professor who has turned to smuggling goods to his love interest, Mama Nadi. These two present perhaps that biggest paradoxes played respectively by the brilliant Tom Pickett and understudy-turned-lead Mariam Barry. With less than two weeks of rehearsal time as a principal performer, Barry’s Congolese accent is notably inconsistent, but she informs other nuances in her delivery to bring the right poise and maternal stoicism to Mama Nadi. A look at the production notes shows a significant age gap between the two lead actors, making Christian many years Nadi’s senior. Their artistry, however, fills that gap. Within the precarious context of the plot the awkwardness of Barry’s pairing with Pickett is not denied; instead, it is integrated into the tension inherent to the plot. Barry doesn’t try to act older than she is, rather mature. Mama Nadi has lived a hard life; she is tough, direct, and a pillar of resilience to the broken community she serves, even as she serves herself. Pickett’s portrayal of Christian complicates the trope of the hyper-masculine patriarch. He is kind and introspective, yet the irony that he brings the women to Mama Nadi for protection is not lost as they are still both complicit in the victimizing the women. In their friendship, we see how compassion survives in the worst of circumstances, even in complicity. As a result, Mama Nadi keeps her affection for Christian, and her interactions with the women at arms-length, a tension that Pickett and Barry affectionately portray. Through everything, Pickett and Barry present a relationship that evolves organically in spite of fear, out of trust, and towards the potential for love.

Makambe K. Simamba and Shayna Jones in Ruined. Photo by Jalen Saip.

In its depiction of the struggle to maintain a humanity that is under siege, Ruined is a timely story difficult to watch. As a black Canadian woman, I look proudly at this challenging and heart-wrenching work by a black woman playwright. Still, I cannot help but feel conflicted about the presence of the predominately white audience and production team (re)watching our traumas played out so unabashedly by the brilliant artists on the stage–on unceded Indigenous land, no less. I wonder how they connect their gender, race, and class privileges to the lives represented on stage. Personally, it compounds the double-conscious experience sociologist and civil rights activist W. E. B. DuBois writes about, adding “woman” and “immigrant” to “black” and “white.” Nottage invites me to view Ruined through many lenses; I hope audiences are doing the same.

This article originally appeared in Alt Theatre on May 18, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Carla Chambers-Jeffreys.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.