Toronto, Ontario

alt.theatre web editor Hayley Malouin reviews the world premiere of Kat Sandler’s BANG BANG at Factory Theatre. At turns delightfully hilarious and grippingly sinister, BANG BANG’s straddling of comedy and drama enables its complex exploration of police violence and artistic license.

On my train ride home from Factory Theatre following the world premiere of Kat Sandler’s BANG BANG, I found myself audibly giggling in remembrance of the play’s dynamite comedy. The next moment, I burst into tears–a fact I failed to hide from the passenger sitting next to me.

This (admittedly embarrassing) response is telling of BANG BANG’s nuanced and moving examination of the array of questions, desires, and emotions prompted by socially- and politically-inspired art. A lesser piece might flounder at the crossroads between comedy and tragedy, not knowing which path to take. These are, after all, difficult times; as we see humor co-opted by fascists and their sympathizers, the capacity for satire to “do good” is thrown again and again into question. In the same moment, atrocities are both sensationalized and de-barbed, rendering the potentially mobilizing capabilities of drama and tragedy equally tenuous. BANG BANG’s resounding power comes from its vibrant occupation of the space between drama and humor, and from its commitment to examining the efficacy of art in the face of injustice through both lenses simultaneously.

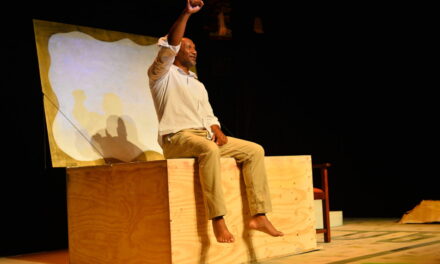

Sébastien Heins, Jeff Lillico, Karen Robinson, and Khadijah Roberts-Abdullah in BANG BANG. Photo by Joseph Michael Photography.

The plot is as follows: young Black female cop Lila (Kadijah Roberts-Abdullah) has recently left the force after non-fatally shooting an unarmed Black youth and now lives with her mother (Karen Robinson). We learn that white playwright Tim (Jeff Lillico) has written a hit play inspired by the news stories surrounding the incident–with the major modification being the fate of the unarmed youth (in Tim’s play he dies). Tim shows up on the family’s doorstep with an awkward and uncouth olive branch on the eve of his play being turned into a major Hollywood film. A frenetic debate about anti-Black racism, police brutality, and artistic license–at times tensely disturbing and disarmingly hilarious–ensues.

Kat Sandler’s script is chock-full of interruptions, interjections, and lines spoken over top of one another, making for an off-the-cuff quality of coming apart at the seams–carefully planned and executed, of course. A clever play-within-a-play structure emerges in a pleasingly organic manner as the piece charges towards intermission. The first half moves like a rocket, quickening its pace with every new entrance and riding the wave of each laugh (of which there are plenty). The second half slows down a tick, partly because the comedy of the first half plays necessary second fiddle to more serious fare. The dysfunction that has crept its way into Karen and Lila’s relationship emerges, and events take several sinister turns.

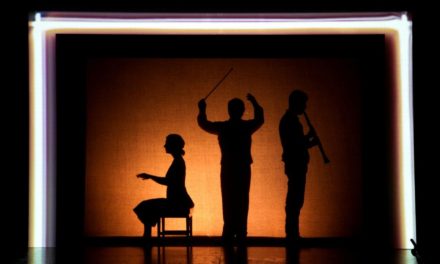

Karen Robinson, Khadijah Roberts-Abdullah, Richard Zeppieri, Jeff Lillico, and Sébastien Heins in BANG BANG. Photo by Joseph Michael Photography.

For a play grilling itself about the implications of writing plays, BANG BANG neatly sidesteps the pitfalls of overly camp self-referential humor by just being honestly, truly, really funny. Richard Zeppieri as Tony, a former cop turned bodyguard, and Robinson as Lila’s mother Karen are particularly hilarious, Tony for his cheerful gaucheness and Karen for her pained looks of derisive displeasure.

Lila, played by the always-excellent Roberts-Abdullah, is bristling with intelligence and anger in equal parts–she’s also thoroughly depressed, a factor Roberts-Abdullah adroitly conveys without falling on infantilizing tropes. Witty quips and familial bickering between Lila and her mother augment these symptoms of depression and trauma–Lila’s lethargy, lack of appetite, and subtle agoraphobia. Roberts-Abdullah and Robinson deftly oscillate between comedic dropouts and serious exchanges with a quietly genius degree of frank vulnerability. As they are bombarded by an onslaught of (male) visitors, including Sébastien Heins as the charmingly tactless former child star turned wannabe serious actor Jackie Savage, Lila and Karen’s fractured mother-daughter relationship remains centre stage and, in the final tender moments of the play, offers the audience its only real sense of reconciliation or closure.

Karen Robinson and Jeff Lillico in BANG BANG. Photo by Joseph Michael Photography.

Jeff Lillico’s Tim–at first comically “woke,” to use his own self-identification–grows more and more unlikeable, much in the way people can do as they get increasingly drunk (which Tim does). His emergent antagonism is a point of interest, especially since Tim represents, at least in part, Sandler’s own intentions and fears as a white playwright exploring themes of race and police brutality. Karen’s damning accusation–that Tim “used [her] daughter as fodder for a play made for White people, that takes them out of the equation and makes them feel better”–acts as a moment of disquieting clarity toward the play’s end, in which the comedy of the previous moment is cast in a new, uncertain light.

I find myself hung up on another moment of disquiet: Tim’s rather too briefly considered Judaism. He emphasizes his last name–Bernbaum–and asks contemptuously if he should be pigeonholed into only writing about Nazis. There is no doubt that anti-Black racism and anti-Semitism function in vastly different ways, and stem from different xenophobic anxieties; while anti-Black racism relies on assumptions of Black inferiority, anti-Semitism is fuelled by (and, indeed, fuels) a fear of preternatural Jewish powers and secret societies bent on dismantling and/or controlling society at large.

Karen Robinson, Khadijah Roberts-Abdullah, and Jeff Lillico in BANG BANG. Photo by Joseph Michael Photography.

Given, however, common anti-Semitic tropes linking these (fabricated) Jewish societies to, first, the international economy and, second, Hollywood’s film industry, there remains a small, unspoken question mark in Tim’s fate of being lathered into a drunken rage at the prospect of not getting to “make it” in Hollywood. The play’s statement on anti-Black racism and the purposefully unanswered questions raised about the limits of creative license are both powerful and cogent; why, then, must racist tropes of Jewish greed be mobilized in order to make them hit home?

Nevertheless, BANG BANG’s commitment to complexity means that such questions are not so much ignored as perhaps left slightly more unanswered than other fraught issues of marginalization. The play’s focus on police brutality explains this prioritization of anti-Black racism, given staggering and sobering statistics, and a strong ensemble of intelligently realized characters ensures that reductive moralizing is avoided at every turn. The result is incendiary wit, paired with gutsy conviction: bang bang.

This article originally appeared in Alt Theatre on May 2, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Hayley Malouin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.