Red, a documentary play created by Wen Hui’s Living Dance Studio, is based on Red Detachment of Women, a model ballet from the Cultural Revolution era. Playwright and dramaturg Zhuang Jiayun looks back on the origins of Red, which takes the body as a model as it retraces history.

In order to write this article, I reread the project proposal that I delivered to the Goethe-Institut back in the summer of 2014. The creation of Red can basically be traced to three main ideas. The first was revisiting the text: we started by reviewing all kinds of material related to Red Detachment of Women (红色娘子军), including archival material, texts, visual and audio materials, and interviews that we had gathered over the three years prior. We were trying to use our documentary play to return to the historical details and individual stories that led to the creation of this revolutionary ballet. From the perspective of the field of dance, we dissected the technical innovations and aesthetic standards of the original work and its particular historical context. The second idea was to explore the dense ideological content of the text and the collective identity that this dramatic platform creates. This part was mainly based on interviews. By sorting through the complex feelings held by a generation of people who experienced the politicization of art and the artification of politics, we analyzed the high degree of integration between national mainstream political ideology and people’s everyday artistic lives during a particular historical period. The third idea has to do with the bodies of the dancers. Their movements sprang from associations with Red Detachment of Women both past and present, both on and off the stage, in order to relate various physical experiences: love, pain, excitement, exhaustion, and so on. Their physical performance in a context that straddles history is an attempt to process the contemporaneity of that period of history.

THE BODY AS A RESEARCH METHOD

The body is naturally an important archival resource for the documentary play. The body used to be defined solely in opposition to the mind, but beginning in the twentieth century, it has been re-contextualized in the fields of anthropology and sociology. It quickly became an important part of the methodology and practice of performance studies. There are many approaches to body studies; with regard to Red, two frameworks are particularly illuminating. The first of the two is the perspective of phenomenology. In this framework, the body is the foundation of the cognitive world, and the human processes of establishing consciousness and forming value are achieved through physical experience. This perspective emphasizes the authenticity, individuality, and subjective initiative of the body as an organism. The second framework is Foucault’s historical and political view of the body, which explores the various impositions of authority upon the body: discipline, transformation, surveillance, and so on. In this (passive) framework, the body is a lens through which we recognize the effects of authority. This perspective emphasizes how history inscribes the body and how politics encodes it. These two views of the body mingle within the overall conceptualization of Red. Based on the memories and imaginations of the body triggered by Red Detachment of Women, we integrated the individual experiences, feelings, and thoughts of each participant (dancers and interviewees), centered on physical expression and developed through certain motifs. We also used the physical expressions of the participants to reflect on the dynamic development of the authority-body dichotomy. In this way, the body is a method, and in Red, bodies, and history are inseparably implicated.

THE BODY SPEAKS ON BEHALF OF THE PRESENT

In 2013, when I was working with Wen Hui (文慧) on Red, I was extremely excited, because as I saw it, the complexity and contradictions contained within and implied by Red Detachment of Women ensured that our excavation and annotation of this mother text would be profound and multifaceted. When we reached the rehearsal phase, we had no script; we were working in the dark. We sought inspiration and drama within the un-themed improvisations of the dancers. Then, we used themed improvisations to develop a narrative and build relationships between the characters. We allowed the dancers to view and listen to the interviews and other materials, pausing whenever they felt inclined to express themselves through movement. We shared our inspirations and our doubts. In order to create a structure, we relied on a table that combined the stories of the four dancers. The table listed their individual reflections on the Cultural Revolution dance training, the ideology behind a model theatre, the contemporaneity of history, and so on. We used these exercises to vaguely and gradually produce a framework for the actions of the dancers as well as an overall expressive scheme with interaction between bodies and visual material. The actual presentation on stage is the result of countless rounds of invention and rehearsal between Wen Hui and the dancers.

During the fifteen minutes in which the audience enters the performance space, the dancers intermittently repeat certain starting movements. Liu Zhuying (刘竹英) chose a movement from Red Detachment of Women: two fists raised upwards. Wen Hui tightly hugs her shoulders inward with her two hands; Jiang Fan (江帆) rapidly brushes her arms against the outside of her thighs and swings them outwards; Li Xinmin (李新民) repeats a chopping motion with her hands clasped together. By gradually developing these starting movements, the dancers express their connection to Red Detachment of Women. These connections lie at the core of each dancer’s individual narrative of the body.

Liu Zhuying’s body plays the role of the model. Her narrative and interview are typical of the experiences of dancers who were born in the fifties and participated in local performing troupes. These dancers felt proud to participate in model plays. Due to ideological cultural products like Red Detachment of Women, they experienced both the discipline and the damage that ballet training delivers to the bodies of dancers; on another level, they were also absorbed into the macro-discourses of revolution, class, and nation that constituted the narrative of proletarian revolution. This narrative gave them identity, honor, and political self-awareness. As model plays promoted a highly concentrated and unified ideology to society at large, the dancers assumed subordinate roles in which the on-stage performances of their model bodies facilitated the dissemination of revolutionary arts and culture.

Wen Hui uses her body to repeatedly perform expressions of pain. Her starting action is a representation of the questioning of autocracy that took place during the New Enlightenment Movement (新启蒙运动) of the 1980s, and an act of conscience-wracking self-dissection as well. Her pain comes from disaffection, and because she is disaffected, she repeatedly calls into question the principles and orientation of model theatre, the collective revelry it generated, and the present-day nostalgia for that revelry. She poses these questions by depleting her own body and using her alienated body language to resist the notion of the body as standardized by revolution and labor. She expresses pain to the audience through movements that challenge the limits of her body. These movements directly demonstrate how history leaves its marks deep in our bodies and how we can use our bodies to challenge the vital political logic of certain historical circumstances.

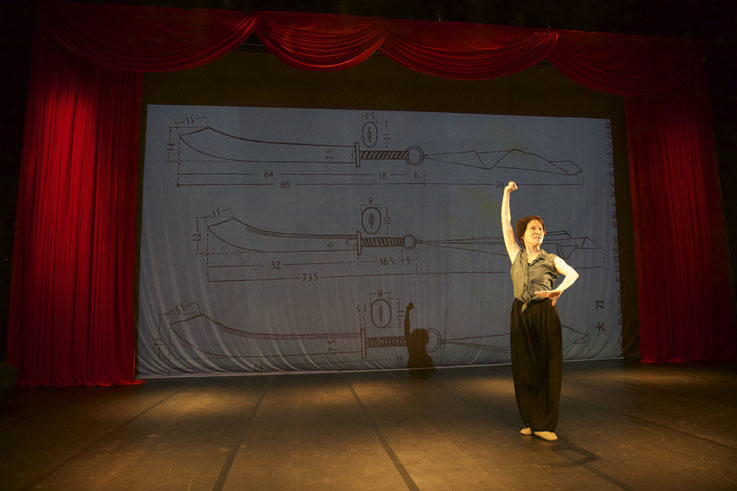

Jiang Fan’s performance has a certain awkwardness to it. A member of the post-85 generation, she studied at a specialized academy and performed in a state-sponsored troupe. She is experienced in the repetitive methods of treating the body as both tool and result. In Red, her individual physical experience is rife with struggles against her fetters, and her socialized/professionalized body is used as a textbook. Trapped in the diagrams that illustrate the angles within which the dancers operate, each of her motions is an explication of the technical operations of the revolutionary ballet. Her hand are frozen in a juxtaposed arrangement: her left, in the “orchid finger” gesture of traditional Beijing opera; her right, in the “tiger mouth” shape associated with model theatre. At the same time, she moves back and forth between the “eight directions” system of traditional dance and the more free-form system of modern dance. Jiang Fan’s natural body repeatedly comes into conflict with the politics of the body, but these two facets are united in her contemporary, Li Xinmin. The ideology presented in Red Detachment of Women can perhaps still find validity in the life of Li Xinmin. Having been born into circumstances of rural poverty, she grew up in a society that prized boys above girls and men above women. Consequently, she chooses violence as the core of her physical performance. She resists the violence of daily life, initially folding her book bag (a manifestation of herself) into an ever-smaller package before eventually using forceful chopping gestures to strike at a violent authority. The object that incites this physical memory within her is the military sword from Red Detachment of Women. The most violent methods of revolution and the politics of the body take on a different significance in the individual experience of Li Xinmin.

Red integrates the body as subject of individual experience with the body as historical and cultural vessel. Using performances of the body, the four dancers express their relationship with Red Detachment of Women, thus creating a means of reflecting on history while also attempting to uncover the motivations behind returning to history.

Translated by Daniel Nieh

Zhuang Jiayun (庄稼昀) earned her PhD in Theater and Performance Studies at University of California, Los Angeles, and received a fellowship from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. She is presently an assistant professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She also serves as dramaturg for the PlayMakers Repertory Company and as playwright and curator for the Beijing New Youth Group (北京新青年剧团). Her research interests include documentary theatre, body theory, performance and urban space, and Chinese folk theatre.

This article was originally published in the online cultural magazine of the Goethe-Institut China. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zhuang Jiayun.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.