In the growing xenophobic atmosphere of Brexit it is a relief to see a show from Europe, to get a foreign eye on the world. And to enjoy a Continental playwriting sensibility about the big theme of globalization. The Pulverised is written by Alexandra Badea, a Romanian-born writer living in France since 2003, and it premiered at the National Theatre of Strasbourg, where it won the prestigious Grand Prix de la Littérature. It takes the form of four alternating monologues which together create a powerful picture of the complexity of economic oppression, a system that stretches across continents.

The four characters are defined not by their names, but by their jobs, by their roles in the organisation of global production. So there’s the Quality Assurance of Subcontractors Manager, a Frenchman from Lyon, who is more often to be found waking up in some anonymous hotel room on the other side of the world, and whose reports on the efficiency of workers he knows little about can affect the lives of countless poor people. Then there’s the Research and Development Engineer in Bucharest, who is preparing a presentation in the hope of getting work from the big boss. Although she is anxious about her baby daughter, whose every move she monitors by means of hidden CCTV in her home, she tries to focus on the exigencies of the job while executives doze as she speaks.

Meanwhile, in Francophone Africa, on the outskirts of Dakar, a Senegalese Call Centre Team Leader runs to catch a bus, his mind full of muddled thoughts about the Second Coming and equally muddled memories of the sexual allure of some of the women on his staff. Then, across the globe in Shanghai, there’s the young Chinese factory worker whose strict work discipline — stand exactly here, do exactly this, don’t stop for more than two seconds —exemplifies the sharp end of the oppression and exploitation of labour by today’s multinational companies. Her work conditions are mirrored by her restricted life in a dorm with other teenage workers.

Badea shows how each of these people is a cog in a vast machine, which is impersonal, instrumental and ruthless. If there is an industrial accident, there is an instant cover-up: documents are faked, witnesses drilled and the company emerges scot free. Her point is that even the privileged European workers in positions of power suffer from alienation and from being part of a crazy system. Instead of the age-old confrontation between boss and worker, here everyone is under the thumb of an inhuman machine, which grinds on irrespective of the needs and desires of its members. Yet surely there is a difference between supervisors and workers, and this aspect of reality is underplayed in this acrid vision of a world where everyone is pulverised by work.

The effects of this pressure, this stress, are a loss of both individual and national identity. The Dakar Team Leader wears a fake Versace suit and insists not only that his phone workers have French names, but also that they eat French food in their lunch breaks. The French Manager begins to lose touch with his young son, despite Skyping regularly and is more fixated on watching a sex webcam than communicating with his wife. The Chinese worker makes boxes for electronic goods in France, but she has no idea what these are. Above her, in this production, hang circuit boards and pieces of smashed equipment that illustrate the pulverisation of the characters’ souls.

What about resistance? A rare moment of conflict occurs when the factory worker begs her supervisor to let her go to the toilet, but he turns this into another instance of humiliation for her. Then when the Senegalese Team Leader tries to flirt with one of his female workers, she answers back. But, once again, he crushes her rebellion by writing a negative report on her. So in these cases resistance to the system — which is characterized as much by the endless repetition of banal slogans as by force — is shown to be futile, which is a rather depressing political message about the total dominion of capitalism in the world today.

Taking turns, each of the four main characters introduces us to typical days in their schedule, and Badea uses the literary device of second-person direct address narrative to tell their stories. This has the effect of creating an immediacy, a closeness and a lyrical and almost incantatory enchantment at the heart of the play. At the same time, by the end of the 90-minute show — and despite the excellence of Lucy Phelps’s translation — this constant envelopment by the characters feels a bit unsatisfying, and is unable to disguise the play’s lack of drama.

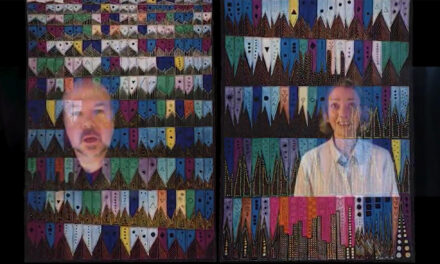

Andy Sava’s production, designed by Nicolai Hart-Hansen (with movement by Lanre Malaolu and video by Ashley Ogden), enlivens the rather static text with some slow motion movement and each of the actors — Richard Corgan (manager), Kate Miles (engineer), Solomon Israel (team leader) and Rebecca Boey (worker) — crumples to the floor as another takes up the story. Although this defiantly anti-naturalistic staging is like a breath of fresh air, a certain staleness comes from the repetition of this gesture, which rapidly seems quite mannered. The Pulverised is a strong account of exploitation, but also feels rather deflating in its implicit advocacy of forgetfulness as a cure for exploitation.

This review was originally posted at sierz.co.uk. Reposted with permission. To read the original review, click here

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.