As someone who has long been fascinated by both of the title characters, I am not sure who Murray Mednick’s new play Mayakovsky and Stalin is for, or about. Mednick, who wrote and directed the play for the Cherry Lane Theatre, connects the two larger-than-life historical figures on the basis of two suicides: that of Stalin’s wife Nadya, and Mayakovsky’s own. There is more, in fact, that connect Mayakovsky, poet of the revolution, and Stalin, but you wouldn’t know it from this play. Nor would you know that Mayakovsky was, in fact, a truly great poet. The linguist and literary theorist Roman Jakobson wrote, “Mayakovsky’s poetry is qualitatively different from everything in Russian verse before him, however intent one may be on establishing genetic links.” A play that puts Mayakovsky’s name in the title, and doesn’t communicate this seismic shift, well, it’s hard to call it a success.

Full disclosure: I recently completed a Ph.D. in Slavic literature, which makes me either the wrong person to review this play, insofar as I cannot view it with any measure of objectivity, or the exact right person to review it. Some of the critiques are undeniably nitpicky, e.g., Lilya Brik’s name was Lilya, not Lily, not Liliana. Other critiques are substantive. Lilya Brik was a person, who loved Mayakovsky and understood that he was, in fact, a truly great poet. In this production, Laura Liguori plays “Lily” as a shrieking bimbo. This is a shame because it tarnishes the legacy of their relationship, which was intimately meaningful, as well as Brik’s own legacy, which was important in Russian culture. If you’ve ever seen the iconic Soviet poster of a woman wearing a headscarf and shouting with her hand up to her mouth, the Russian word “книги” [“books”] blasting out of her mouth, then you’ve seen Lilya Brik, in an image created by the revolutionary designer Alexander Rodchenko. In 1935, Brik wrote a letter to Stalin, beseeching him to posthumously rehabilitate Mayakovsky, an episode which features as a plot-point in this play. It makes little sense in Mednick’s world because both Brik and Stalin are negotiating Mayakovsky’s legacy in spite of their shared low regard for his poetry. In reality, Brik’s letter to Stalin was an extraordinary act, audacious and deeply intelligent.

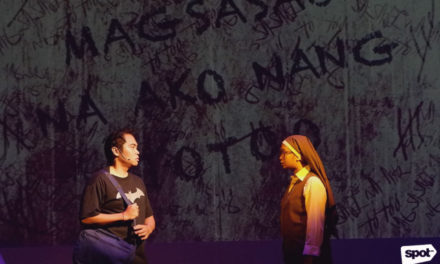

Laura Liguori as Lilya Brik, in front of a photo of Lilya Brik used by Rodchenko as the cover for a poem by Mayakovsky about Lilya Brik. Photo by Russ Rowland.

Unfortunately, Mayakovsky himself is no more fleshed out. In Daniel Dorr’s portrayal, he becomes a kind of caricature, first of a puffed-up poet, then of a poet gone mad. It doesn’t help that the rest of the characters constantly denigrate Mayakovsky’s poetry, leaving the uninitiated audience member with the impression that Mayakovsky’s verse wasn’t worth a kopeck. There are two options here for interpretation of Mednick’s Mayakovsky: either he is stripped of his historical specificity in order represent an archetypal poet, a delicate creature who cannot survive under authoritarianism (represented by Stalin, one of the characters who denigrates his poetry), or what we’ve got here is a failure to communicate.

Throughout the play, Lilya and other characters throw around the term “Futurism” as if it symbolizes Mayakovsky’s overblown ego. As if he’s too good for his own time period. If Mednick had taken the time to explain Futurism, it would have contextualized both Mayakovsky and some of the images, including Rodchenko’s famous poster, which briefly appears in the background of the stage. Futurism was a movement in literature, cinema and the visual arts that promoted a break with traditional culture and embraced technology. In a 1912 collective manifesto titled “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste,” they famously declaimed, “Throw Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc., etc. overboard from the Ship of Modernity.”

These values are why the Futurists and other avant-garde artists embraced the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1920s, many prominent members of the Russian avant-garde started practicing the commercial arts and teaching, part of their commitment to creating high-quality but reproducible art for the masses. That’s why early Soviet propaganda, with its bold lettering and collage techniques, looks so damn cool. That Rodchenko poster, for example. Hana S. Kim’s scenic design, which includes layered photographs of the two title characters and stretched text, nods to these principles of Russian avant-garde design. But, as is often the case, Cyrillic lettering in an otherwise Anglophone production ultimately has the effect of “othering” Russian culture.

Mayakovsky was the leading avant-garde poet and playwright, and his suicide in 1930 is widely understood as the end of the exuberant, optimistic, artistically productive revolutionary era, and the beginning of the repressive Stalinist era. That, from a historical perspective, is what connects Mayakovsky to Stalin. Suicide is a mental health crisis, but Mayakovsky was not, I don’t think, such a raving lunatic as he appears in this play. Rather, he saw the writing on the wall.

The scenes with Stalin and Nadya were, to my mind, more reasonable. Maury Sterling plays Stalin as a sort of boorish CEO, sexy and powerful and unabashedly reliant on his yes-men. (Lest we forget, though, in his youth Joseph Vissarionovich also wrote poetry, verses not nearly so avant-garde as Mayakovsky’s.) Jennifer Cannon as Nadya is strong in her frailty, thoughtful though pushed to the brink. The suicidal, her performance reminds us, are not always hysterical, It is occasionally a reasonable choice, as perhaps it was for Nadya, and later, though this is not included in the play, the terminally ill 87-year-old Lilya Brik.

Jennifer Cannon as Nadya. Photo by Russ Rowland.

In the play, Nadya and Mayakovsky are linked, as suicides. So are Stalin and Lilya Brik as, at least in Mednick’s vision, brutes who don’t appreciate their sensitive lovers and drive them to suicide. I wish the play had been called “Stalin and his wife Nadya,” and had focused on that relationship, that conflict, which was better written, better acted, more convincing and more meaningful. But because, even after a two-hour performance, so much more remains to be said about Mayakovsky and the meaning, artistic and historical, of his poetry, I’ll give the last word to Jakobson. Jakobson’s characterization of the poet which I quoted earlier comes from the essay “On a Generation that Squandered Its Poets,” written on the occasion of Mayakovsky’s suicide, which I also quote here. The [notes] are mine:

The basic fusion of Mayakovsky’s poetry with the theme of the revolution has often been pointed out. But another indissoluble combination of motifs in the poet’s work has not so far been noticed: revolution and the destruction of the poet. This idea is suggested even as early as the Tragedy (1913), and later this fact that the linkage of the two is not accidental becomes “clear to the point of hallucination.” No mercy will be shown to the army of zealots, or to the doomed volunteers in the struggle. The poet himself is an expiatory offering in the name of that universal and real resurrection that is to come; that was the theme of the poem “War: and the Universe” (“Vojna i mir”)[note: this is also a translation of Tolstoy’s novel, War and Peace; the Russian word “mir” is a homonym meaning both “war” and “the world”]. And in the poem “A Cloud in Trousers” (“Oblako v stanax”) the poet promises that when a certain year comes “in the thorny crown” of revolutions, “For you/ I will tear out my soul/ and trample on it till it spreads out,/ and I’ll give it to you,/ a bloody banner.” In the poems written after the revolution the same idea is there, but in the past tense. The poet, immobilized by the revolution, has “stamped on the throat of his own song.” (This line occurs in the last poem he published, an address to his “comrade-descendants” of the future, written in clear awareness of the coming end.) In the poem “About That” (“Pro eto”) [note: a poem about the desperation to which he was driven by love and desire for Lilya Brik] the poet is destroyed by byt [Russian: “everyday life,” but in a deeply regrettable, almost elegiac sense]. “The bloodletting is over. . . Only high above the Kremlin the tatters of the poet shine in the wind—a little red flag.”

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.