“Philippine theater has, through three eras of political struggle—Filipino-American, Japanese, anti-Marcos—never hesitated to go to war.” – – Doreen G. Fernandez, “Seditious and Subversive: Theater of War”

From the essay cited above two important ideas emerge: that war breeds theatre and that theatre is a particularly effective weapon of protest. As Fernadez’s survey shows, the Philippines has a heritage of political plays, which began in the 1900s, when plays labelled “seditious” by Americans were suppressed because of what they could do: stir the audience to “such a pitch of indignation and enthusiasm that they could leave the theatre full of purpose against the government and its emissaries” (Riggs 349).

Decades later, during the martial law years, the tradition of protest theatre made it possible for plays to “stand beside the people, against the enemy,” as Fernandez puts it. At first, subversive themes were woven into historical plays and folk theatre fare. As anger grew, plays became more confrontational, overtly calling out human rights violations and decrying Marcos as a monster.

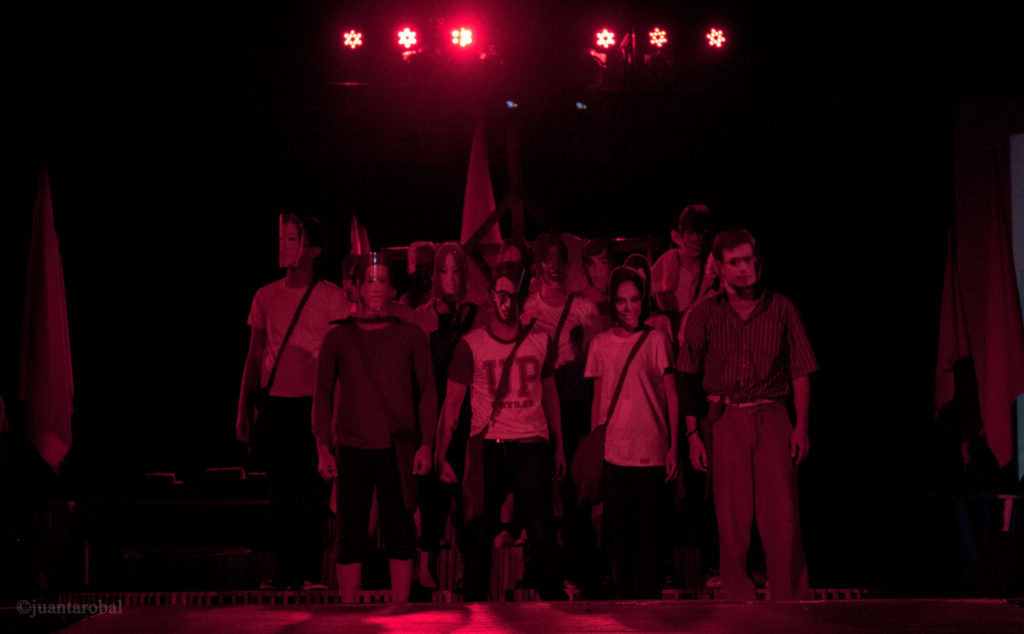

Bonifacio Ilagan’s Pagsambang Bayan staged at various venues in Metro Manila and nearby provinces. The contemporary rendition of the play revisits the Martial Law period under the dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos with parallelisms with the current administration of the Philippines. The play turned musical is directed by Joel Lamangan (Photo: Tag-Ani Performing Arts Society Facebook Page)

In 2016 and 2017, the theatre took up the gauntlet once more via the staging of protest and advocacy plays, among which are two martial law musicals that confront the horrific realities of the Marcos era while linking these to those of the present regime.

In one, the weapon is wielded, so to speak, by children. The Raya School Manila’s Isang Harding Papel is a musical adaptation of Augie Rivera’s children’s book, published in 2014, about a young girl whose mother is a political prisoner during the martial law period.

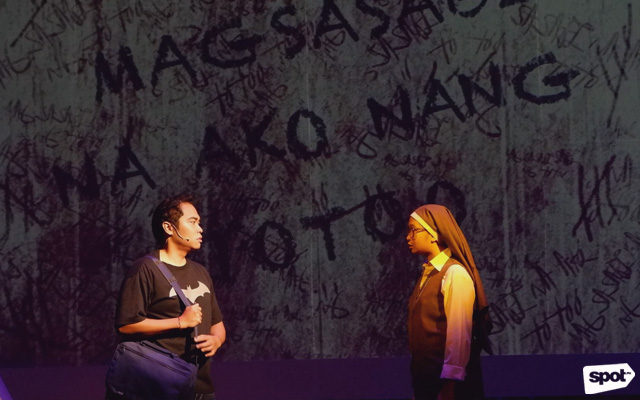

A scene from Isang Harding Papel, a children’s musical based on the book by Augie Rivera, music by Thea Tolentino, book and lyrics by Nanoy Rafael and directed by Nor Domingo (Photo: https://www.spot.ph/arts-culture/performing-arts-2/68956/isang-harding-papel-rerun-free-tickets-a00171-20170113)

The goal of the production starred in by Raya’s pre-schoolers and grade-schoolers, is to teach children today about human rights violations, graft, and corruption under former President Ferdinand Marcos. The adaptation expands the story to include scenes of detainees being tortured, the New Society’s enforcement of discipline, and the abductions and “salvaging” of subversives—artistically woven into the heartbreaking story of a daughter separated from her mother. The play, like the picture book, is hopeful and bittersweet, as it ends with a revolution and happy reunion many years later. Yet the final chorus, sung by childish voices and juxtaposed with today’s Extra Judicial Killings (EJK) statistics flashed in the background, urges the audience to remember that the fight is not over: “Bayan ko, o bayan ko, ‘di pa tapos ang laban mo/’Di pa tapos ang laban – ipagpatuloy mo!” (My motherland, my beloved country, the fight is not yet over, it is not over – we will continue fighting for you).

The second of these plays exploits, at least in its title, the popularity among young people of G.R.R. Martin’s fantasy series. A Game of Trolls or AGoT features as its protagonist paid internet troll Hector, who heckles netizens posting against martial law, but who is then haunted by ghosts of martial law past. The musical was staged early in 2017 as the Philippine Educational Theater Association’s (PETA’s) response to the burial of former President Marcos in the Libingan ng mga Bayani (Philippine Heroes Cemetery).

Clearly targeting the youth, it features a cast of millennial characters and heavily references social media platforms and technology as well as, in its upcoming run in September, the victims of President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs. The message, says writer Liza Magtoto, is for them “to look beyond the memes and the online propaganda that [has] become so accessible because of social media, to encourage them to do their own research, to think critically, and to act with responsibility” (qtd. in “First Look”).

These two plays were staged and then re-staged, due to popular demand, within the early months of a new administration. Clearly, when history comes under attack by revisionists, when the victims of a fascist government are forgotten, when the horrors of the past return to haunt the present, then theatre serves as both warrior and weapon in a new war for the Filipino people.

Works Cited:

Fernandez, Doreen. “Seditious and Subversive: Theater of War.” NCCA. National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 17 Nov. 2003. Web. 28 August 2017.

“First Look: PETA Back in Protest Mode with Martial Law Musical.” ABS-CBN News. ABS-CBN, 12 Dec. 2016. Web. 28 Aug. 2017.

Riggs, Arthur Stanley. The Filipino Drama [1905]. Manila: Intramuros Administration, 1981.

Rivera, Augie. Isang Harding Papel. Quezon City: Adarna Books, 2014.

This essay first appeared in the palabas.org of the Philippine Performance Archive Project of the University of the Philippines Diliman. Please click here for the original article.

*Maria Lorena Santos earned her PhD (English Language and Literature) from the National University of Singapore. She is currently a faculty member at the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the University of the Philippines Diliman.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Lorena Santo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.