Feminist themes, whether overt or subtextual, found expression in the plays that were showcased at this year’s edition of the NCPA’s Pratibimb Marathi Theatre Festival, from 5th – 9th August 2017. The selection certainly boasted a diversity of themes and theatrical approaches as classic scripts rubbed shoulders with new writing, and traditional forms shared the same podium as more contemporary idioms. Returnees to the festival from the last edition included prolific director Atul Pethe and actor Rajashree Sawant Wad, who have collaborated on the period drama, Samajswasthaya, produced by Natakghar, Pune.

Forever topical

One of the highlights of the festival was Aniruddha Khutwad’s revival of Mahesh Elkunchwar’s discursive zeitgeist saga Party. It is most famous in its 1984 Hindi film adaptation by Govind Nihalani, which lacked cinematic flair but brought Elkunchwar’s preoccupations to the fore at a time (circa 1975) when progressiveness in the arts, radical or otherwise, was soon to buckle under the yoke of Emergency-era oppression. In Khutwad’s play, Prajakta Pandhare played the feminine figurehead — culture czarina Damayanti Rane, — who invited the art world’s jet set to her mansion for a soirée, in which these tensions bubbled to the surface and the hypocrisies rife in so-called enlightened spaces lay exposed.

Khutwad’s play arrived in Mumbai after performances in Pune, where it opened at the Jyotsna Bhole Sabhagruha in February. While still set in the turbulent 1970s, there was something very topical about the play — particularly in the liberal hand-wringing that still afflicted the art cognoscenti, and the perils of an impending cultural crisis that many may be taking too lightly. Elkunchwar’s world-view then was still inchoate so it was interesting to see if Khutwad upgraded the play’s sensibility enough to strike a contemporary chord with audiences.

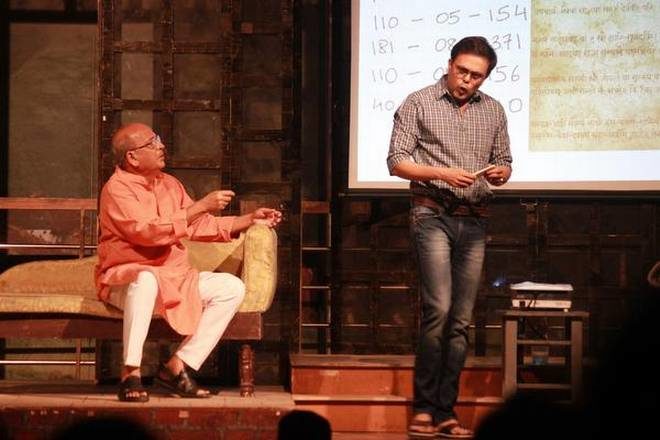

Similarly, Pethe’s Samajswasthaya, set in the 1930s dealt with subject matter that is still relevant today, if the Lipstick Under My Burkha imbroglio was any indication. The title of the play referred to the Marathi sex literacy magazine published by Raghunath Dhondo Karve (played by Girish Kulkarni) for almost three decades from 1927. Due to its uninhibited advocacy of the sexual freedom of women, it was a publication way ahead of its time, but Karve remained one of the most marginalized social pioneers in history and faced several obscenity trials which the play trained its focus on. It was thus not biographical in the manner of Amol Palekar’s film on Karve — Dhyas Parva — but sought to capture the essence of a progressive man blighted by primeval social attitudes. Sawant Wad played his supportive wife Malati as an equal partner in his exploits and triumphs. Pethe also introduced B.R. Ambedkar into his narrative as one of the most vocal champions of women’s rights who wholeheartedly supported Karve’s work. As the play moved from court case to court case, its style of presentation changed from naturalistic to the surreal, in an attempt to highlight the absurdity of the situation.

Feminist themes

Of course, the unbridled and unapologetic expression of feminine sexuality was one of the defining features of the deliriously popular Sangeet Bari, from Kali Billi Productions, via lavani performers like Shakunatala Nagarkar and Pushpa Satarkar. Its Hindi version was recently showcased at the NCPA’s Ananda Hindi Natya Utsav, and its inclusion at the festival spoke of how the form itself transcended the barriers of language, and how its eroticism had a universal cadence. Alongside the performance of rare lavanis by actual exponents of the form, a commentary by writer-director duo, Bhushan Korgaonkar and Savitri Medhatul, contextualized the form for the uninitiated.

One of the contemporary plays at the festival was MH12J16, from the Pune-based Prayog theatre group. Written by Vivek Bele and directed by Subodh Pande, the play won top honors at the Maharashtra State Marathi Theatre Festival, held earlier this year. It’s perhaps self-referential, as the protagonist was a young female playwright who was negotiating the cesspool of commercial theatre in Pune, while still attempting to hold on to her artistic integrity. The “play within the play” was a chamber piece exploring human relationships, and Pande effected a kind of forum for change, in which the playwright entered into communion with both her director and her audience. The latter is represented in the person of a woman in her 50s, who was ostensibly a member of commercial theatre’s most faithful demographic and sat at what is the most central spot in a standard issue auditorium — seat J16. The title was a portmanteau of that seat number, and MH12, the car registration designation for Pune. This window into the tropes of theatre-making also included social commentary, as the playwright was able to subvert the insidious hold her director had on her craft, by winning over a discerning audience.

Also in the itinerary was Rujuta Productions’ Ek Shoonya Teen, dubbed a “feminist murder mystery.” Loosely adapted from Stieg Larsson’s The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, the play was directed by Sudeep Modak and Neeraj Shirvaikar, and concerned itself with the disappearance of a young woman some 20 years back, while foregrounding a motley crew of “interested parties” who threw themselves into solving the whodunit. Adapted by Modak, the play operated as an indictment of Hindu patriarchy, and Swanandi Tikekar created an unusual leading lady in the path-breaking mold of Larsson’s Lisbeth Salander, so memorably essayed by Rooney Mara.

Rounding up the selection were two more plays. Hey Ram depicted the Bohada mask festival held in Thane and Nashik during Ram Navami. It was based on a story by Sadanand Deshmukh, adapted for the stage by director Ram Daund, for the Vijigisha Foundation. The opening play, Mumbaiche Kawale, was a satire written by Shafaat Khan 40 years ago, and was among his most translated works. Presented by Awishkar Theatre, and directed by Priydarshan Jadhav, the farce unfolded in a village reeling from the effects of a natural calamity, that wiped out homes and livelihoods, but not the differences of dogma.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.