This year is the 125th Anniversary of the famous gothic novel written by the Irish writer Bram Stoker – Dracula. 125 years have passed since the book was first published in 1897 by Archibald Constable and Company. Over 900 screen versions, numerous stage productions of various genres – is clear evidence of the never-dying interest in the main character of the novel – Count Dracula.

Many years later, having discovered some lost journals and notes of the writer, his great grand-nephew – Dacre Stoker, created and co-authored a sequel, and then a prequel.

The play Dracula: Finding of a Shadow, written by Lisa Monde, is inspired by the events happening in all three literary works – the original Dracula, the sequel Dracula the Un-Dead and the prequel Dracul.

This Halloween, the Gene Frankel Theatre is preparing an original production of the play. Unfortunately, due to a busy schedule, Dacre Stoker is unable to attend the premiere, but he was generous to record a video message to the spectators of the Gene Frankel Theatre and to speak to Lisa about Dracula, his famous relative and many other interesting and otherworldly things.

Dacre Stoker. PC: Neal Rylatt.

Lisa Monde: I know you have been very busy lately. First of all, Dacre, thank you very much for this meeting and this interview. I’m very excited to talk to you about Dracula! Tell me, how did it all come to be, how and why did you decide to write first the sequel and then the prequel to Dracula? What was your inspiration?

Dacre Stoker: Well, the original idea was: the story of Dracula really didn’t end in the manner in which Bram Stoker wrote his novel and described how a vampire was supposed to be killed. And so, I looked at this opportunity and I thought: “Well, he explained through Van Helsing how a vampire can be killed with a wooden stake, cutting the head completely off and inserting the garlic.” And that is understandable. Bram got that from superstitions that he read through Emily Gerard’s The Land Beyond the Forest and we know where that came from in the story. However, what was really an amazing issue to me, was knowing as detailed as Bram was, how come at the very end of his novel, and this is not the same way as things were portrayed in some movies and staged plays, and you know this, Lisa, that Bram had Jonathan Harker slit the throat of the Count and Quincey Morris stabbed the Count with the buoy knife, so there was no stake involved. And the Count got this look of peace on his face, and he crumbled into dust at the end. Was that his demise? Was that his cheeky escape, that look of peace on his face and at dusk? What was it? Also, the fact is that upon my research I found that right after that scene Bram originally planned a volcanic eruption. That was edited out of the typescript. So, he planned a very definitive ending but that wasn’t meant to be. That volcanic eruption was crossed out of the book with a number of lines and the Count was only stabbed with a knife, so I figured: “There’s got to be some reason for this. Did he plan a sequel himself? What was it?” So, hence – no sequel, I decided with Ian Holt that maybe we should do something to replace that. And that’s why we pick up the story with Dracula the Un-Dead 25 years after the story ends. The young child, that was born in the novel, young Quincey, who they named after Quincey Morris who died in the fight against the gypsies that were guarding the count – the heroes come back to Transylvania to pay homage to Quincey and to, sort of, reckon, I guess, all the horrible stuff that they went through themselves to rid London of this inherent menace 7 years later. But we decided… Ian and I said – “Look, we need to have this character old enough to run the story” and Ian is involved with the stage, much like yourself, he’s an actor. So, our Quincey started wherewithal asking his family – “What happened? Just what went on?” Which is, what many people in their twenties begin to do. But our Quincey stumbled onto things that ended up being sort of the opening of the proverbial Pandora’s box and everything went from Good to Bad to really Evil, when, no surprise to anybody – Dracula is not dead after all! I’m just not going to tell, you guys, how he reappears, where he reappears, or when. To avoid any spoilers. But that was the basis, Lisa, for the continuation of the story. And also, as you said at the top of the interview, we wondered what happened to all these people? You know, Ian and I had this discussion – the main heroes of the original novel went through major trauma: they had to kill Lucy themselves, they lost Harker, they were putting themselves at great risk to chase this vampire back to Transylvania – it wasn’t easy. So, would their lives just go back to normal after that? I think not. And I also think about Doctor John Seward, who didn’t get the woman, when Holmwood married Lucy… All of it. So, then you begin to wonder about other little things – like Jonathan’s employer – Peter Hawkins, how did he die and how did he leave the business affairs for Mina and Jonathan to deal with? These other little things were sort of “under” the original plot and there’s more to Dracula than what meets the eye. So, hence, in Dracula the Un-Dead, in the process of doing my research for that and trying to figure out who was Bram Stoker and what were his motivations for writing the story, I found his lost journal in an attic on the Isle of Wight, that his great-grandsons owned. That helped me to really understand much more about Bram as a person and we’ll talk about it more… but that was the original impetus for me, as I understood Bram and some of the strange and weird things that had happened in his life. I realized – there’s got to be a story about him writing Dracula. What inspired Bram? What were his motivations to write Dracula? So, that gave J.D. Barker and I the entrée as I looked at his childhood illness -it was something I really got fixated on – I said: “How does a kid go from being an invalid for 7 years and then, by some miracle, become a champion athlete at the age of 17 at the Trinity College? Winning all kinds of awards and things?” It just didn’t add up. And that’s where we started, as many authors do, and yourself included, you start to… and a glass of wine or two helps here, you start to think “what if”. What if this novel was a warning to the world that vampires are real? And how Bram Stoker has dealt with that? And the way I sum it up – and then I’ll give the floor back to you, was if Bram- the respected theater manager, went to the Scotland Yard and the Metropolitan Police and said: “You know, I’ve got reason to believe there’s a vampire out there…” Especially on the heels of the Jack the Ripper murders – and the police couldn’t catch him… They probably would have thought Bram Stoker a little wacky, they may have put him in an insane asylum… So, I think, in my writer’s mind, Bram Stoker did what any good writer would do – he wrote a story where he worked the world his way. And this was the impetus for J.D. Barker and myself to write Dracul in the way that we did.

LM: Interesting. My play Dracula: Finding of a Shadow, – was inspired not only by the original Dracula, but also by the prequel and the sequel, that I read, and I thought, ‘Yes, we need to include Bram and make him one of the characters, bring him face to face with vampires and see what happens. Explore Bram as the author: how did Dracula come to be? What influenced Dracula?’ So, I followed a couple of plot lines that were suggested in your sequel… Like I said that idea of bringing Bram face to face with a vampire, revealing some of Bram’s childhood fears, that later on gave birth to the character of Dracula – seemed exciting! So, what are your thoughts on these childhood fears that Bram had suffered from, about which you learned from his diaries? How did that effect his life as the author, his creation of Dracula?

DS: I guess to start with, the diary that I found didn’t start until Bram was a university student. So, my theories on his childhood traumas that he suffered come out of circumstantial evidence, but enough of it that I believe that it holds water, Lisa. Here are the facts that we know of: from zero to 7 Bram had some mysterious illness, we don’t know what it was, but what I’ve put together is from a little blurb he wrote in Personal Reminiscence of Henry Irving – which is a tell-all story, not nitty gritty, but it was a story of Bram Stoker and Irving over 27 years – a huge 2 volume book that became a best seller because, of course, Henry Irving was a massive deal in his days and Bram was right there by his side, every step of the way. Knowing the type of person that Bram was from those journals – he wasn’t going to go into much detail about himself, he was too humble a person. What I think was actually ailing Bram – was a very serious case of respiratory allergies that he had, and it made it very difficult for him to breathe from time to time because of the musty and mildewy environment that he lived in on the shores of Dublin harbor in Clontarf. So, there was almost no escape from those allergies. They didn’t have all the necessary medications, obviously, but what they had was bloodletting. I think Bram was probably blood-let repeatedly. And when I look at the writing of Dracula, where he actually mentions in Chapter 7 or 8 when Harker stumbles upon Count Dracula in his crate, in the coffin, where he says that the Count looks like he’s had his full replenishment of blood, “he looked as a filthy leech” – I think Bram got that from his first-hand experience. Where, as a child, he was drained of blood until he passed out and rehydrated with the help of a mixture of oil and claret – sweet red wine. So that trauma, that state of hazy consciousness, I think, contributed to his macabre sense of imagination. But also, when you combine that with the stories he was told: his mother and nanny, to keep him interested, were telling him all kinds of Irish cautionary tales – banshees, changelings, pookas, fairies, their own versions of vampires were just as scary as the ones in Transylvania. They just happen not to look like Bella Lugosi all these years later, but they were these bloodsucking creatures like our boogyman… We have a record of one of the stories his mother actually told him, which is her childhood experience as a 12-year-old in 1832 – narrow escaping death herself during the cholera epidemic in Sligo, where she witnessed people being misdiagnosed and premature burial. So I just can’t imagine what little Bram would be thinking. “What if they misdiagnosed him and buried him prematurely?” And as a story within the family, I’ve been told that Bram was known to suffer nightmares throughout his life. And I believe they probably started with all that I just described to you. I should also mention, that nightmares during the Victorian era were actually considered to be a sign of demonic possession. So, this was a time when you’re vulnerable, the bad spirits get in, they take over your body, they give you these crazy ideas… Bram did his research and found out the same thing about trans-walking and sleepwalking and somnambulism. It all kind of comes together – that all this stuff was happening to this little boy and then, as Sigmund Freud would say, it all comes out later in life, when Bram hits pen to paper and starts writing Dracula. So that’s kind of long-winded, but that’s what I found to be the basis for all of this.

Dacre Stoker. PC: Neal Rylatt.

LM: I also was wondering about Bram’s attraction to the ground, the soil, and that idea of being buried alive. So, it seemed, at least from the prequel, that at first, he was terrified of that and of the stories about people being buried alive but then he developed some sort of interest – like he really wanted to experience it himself in a way. How is it to be in that ground? Did it, perhaps, feel safer to him? Than to be outside, in the open air, in the fields. It was safer and felt “cozier”, somehow better for him to be in a closed-up space and in the ground… Like when him and Matilda removed the mattress from Nanna Ellen’s bed, where she was sleeping in the prequel and there was ground under the mattress. And he felt that pull, thinking: “Hm, it would be nice to lay down and experience it and feel that soil beneath you”.

DS: Well, not for me, I’m claustrophobic personally. I couldn’t handle that. Just writing those things with J.D. gave me the willies. But yes, you begin to wonder where did that come from? I can’t help but think of the horror of being put in the ground and covered up prematurely. And was Bram, because he was confined to his bed for 7 years, was he more comfortable in his little room, in his little cocoon, so to speak, rather than being out and about, where he was being shielded from the places where there was more moisture, more illness that made him vulnerable? Who knows? But I think that you’ve hit on something here, yes.

LM: I think it explains certain things for sure. Now, the loaded question is – do you think, that Bram actually believed in vampires?

DS: I’ll tell you this, I wish if I was granted one question and a visit to my great grand-uncle and I saw his spirit – I would ask that very question. I am convinced that he believed that many people did believe in vampires. In his research, that he mentioned in the one interview that he ever was asked to give to Jane Stoddard of the British Weekly a couple of months after Dracula came out, when she says “Where does this myth of the vampire come from?”, he goes into great detail about what was going on in the middle ages in Europe when these contagious diseases were going through the cities and people who didn’t understand germ theory were connecting these multiple deaths, days apart, to something supernatural, that people who had some sort of disease that they succumbed to were convinced that their spirit was coming back from out of the grave and drinking blood from others – all of this was vampirism. And I think, Bram latched onto that. Since we’ve got some scientific things going on without proper understanding, people would rest upon superstition. So, I can’t say what Bram was thinking, but I know he latched onto the fact that he believed that other people did believe and that was everything for him to make this book feel real, as well as placing it in real time – the plot unravels in 1893. The book was published in 1897. Real people involved, and he merged different people from his life to make it even more real – real places, real events, real scary.

LM: Yes, real scary indeed. Perhaps Bram mentioned something in his diaries or in his notes…. At the time, most of the people were coming from very religious families and religion was a part of people’s lives big time. How did Bram balance that religious part of his upbringing with the society believing in these monsters and tell-tales? How did he manage to maintain that balance between the existing morals and ethics and beliefs of the contemporary society?

DS: It really was an interesting time, Lisa, and what we’ve got to consider is what were those beliefs and interests at the time? At the end of the 1800s there was a big movement towards the occult, for the purposes of understanding things that have been shoved their way for many years, which was the approach of the traditional religion – “Don’t question the church, whichever God you worship, whichever priest or priestess or clergy, vicars that you listen to on certain days of the week – don’t question anything”. Now they are beginning to question those things. Part of it had to do with the scientific revolution, people beginning to understand how things were working and they wanted to know about life and death and where the spirit goes. So this was not unusual for people to be questioning religion a little bit. And people like Bram Stoker – he was a protestant, he was brought up predominantly in catholic Ireland, he was practicing. And in his own little Bible that I found, when he was 11 years old, he underlined a couple of things and one of them was “Resist the Devil, have faith in God”. Bram was still saying: “Even though this is a great time of change and science is getting involved and running our lives and helping us make decisions, and we’re questioning God and so on… we need to keep our faith…” Because by staying good and by being good people – basically, we’re looking at Good vs Evil, “…recognizing the role of the Devil, recognizing God and following the good work will help you through, even in the face of the Devil and the supernatural that we don’t quite understand.” But “stay together”.” And this band of heroes of the novel banding together to defeat this evil thing by using religious icons like the cross, like the holy water, like the wafer, even though there is this incredible similarity between drinking Jesus’s blood on Sunday at mass and drinking the blood – that blood is the life for the vampire who takes the blood from the living… There’s that similarity. And I think what Bram was doing – he was blurring the edges of Good vs Evil into a gray area to make people really think. And this is what he did so well. He didn’t say “there’s no place for religion” and he didn’t say “religion can save everything”. It was this gray area that made us really wonder – if this Evil is coming, how can we best protect ourselves?

LM: Love that part. So, I know that the original text of Dracula by Bram Stoker was a little bit different from what we have today, as a published book. There is a darker and gorier version of it, which was published in Sweden, I believe, in the beginning of 1900s and it was called Powers of Darkness. The Lost version of Dracula. I’m wondering, since you know that text… Dracula by Bram Stoker became the basis for many movies, series, plays and musicals, and it’s “softer” than that version of Powers of the Darkness. According to you, what are the major differences between those two versions of Dracula?

DS: To sum it up, Lisa, what happened was, when Dracula was published in 1897… We know where Bram’s notes are currently – in Philadelphia, at the Rosenbach Museum, we know where the typescript is, so we have a pretty good idea of what went into the writing of that book and that’s what I do my lectures on. But what entered into the fore in 2015 and actually started in 1989, was that Richard Dolby actually found this preface to the Icelandic edition being significantly different. So, the book was published in Iceland in 1901 but it was serialized in a newspaper before that in Sweden in 1898, I believe. Or 1899. So, what happened was, that in those days for authors to have their book published in a foreign country, and a lot of countries did this, they required the author to submit a manuscript so it could be serialized in a newspaper before it gets published into a book. And when that happens, the original author loses a little control over his written word. First of all, Bram didn’t speak Swedish or Icelandic so I don’t know if he ever knew that the version you’re referring to – The Powers of Darkness, was such a dramatically altered story. And for your readers, not only is the preface more realistic and makes the story sound like it really happened, but also the names of the characters were changed slightly, the book was about another one third longer than Dracula was. There was more sexuality involved, more violence. But probably the biggest thing was that Count Dracula had a more defined and purposeful reason for coming to London. In Bram’s Dracula, as we continue to talk about it, the Count came to London, he converted a couple of people to vampires, and then he was chased home. But in the Swedish and then Icelandic editions, he’s actually, in a very sophisticated manner, corrupting ambassadors and politicians. To adhere to a much more fascist type of political overthrow of the government. So, many of us believe, and it’s been 7 or 8 years, people like Hans De Roos, Rickard Berghorn, who have been really studying this like crazy, I’ve written forewords to their translations, and given my opinion, and this is what it is in a nutshell, Lisa: there is no proof that Bram Stoker wrote or was even aware of these contributions. There is no typescript or manuscript of this longer edition with these additional changes anywhere. So we don’t know if Bram had a hand in it. There are theories that the translators, along with editors of these newspapers, in both countries decided to spice it up. And make it more relevant for their readers. Why? To sell more newspapers. And then they came up with this version that when you look at the political and social situation in Scandinavia at that time of history, they were much closer to the rise of fascism in Germany and they were really scared of it, there was social Darwinism that was going on, people really worried about how the ethnic groups should be treated… So, it stands to reason, and again, Lisa, this is just my circumstantial evidence turning into an opinion – that Bram probably didn’t have a hand in writing that book because in none of his books, was he overtly political or making big statements. As a matter of fact, in the one interview that he ever gave when Jane Stoddard asked: “What is the purpose to your writing?”, Bram said – “None really, I prefer to let the readers figure it out for themselves.” So I don’t think he was really trying to make a political statement and so the history lives on. Maybe, in another 125 years, someone will find who actually contributed to this writing, who was the genius behind the story, because it’s a bloody good story!

LM: Makes sense. Alright, now, I was wondering, when it comes to Bram’s fears again – maybe there was something in his journals? And I’ve noticed some of it in the prequel as well. Because Bram was experiencing all of these fears and illnesses, were these fears in the way? Did he want to rid himself of them? And if he did- what did he do to achieve that? I guess, part of that question is a little straightforward – did Bram ever turn himself to alcohol or drugs? To get rid of these fears and nightmares that he experienced. Is there any confirmation that he actually used those substances throughout his life?

DS: No. It sounds dull and boring. In real life there is no confirmation whatsoever that he did. The sad thing is, he had enough problems as it was with his own health, which is what I used in our story, and I’ve got to be careful about revealing too many spoilers. So, what happened in real life was, Bram started suffering from health issues later in life – after a stroke he began to lose the sight in his eye, he suffered from Bright’s disease – which was kidney issues, he suffered a final stroke at the end. It was a sad ending to his life, Lisa. Bram simply wore himself down with a hard lifestyle. And what J.D. and I did, in Dracul – we connected this to “Was whatever healed him as a child catching up with him?” And as we say, we’ve always got to pay the piper at some point in life. Maybe that healing power was over as he really wore himself down in real life. I think, Bram was pretty straightlaced, had enough problems with his own health, he didn’t need anything extra.

LM: My next question is, when you find yourself in possession of someone else’s diaries or journals, there’s this temptation to adjust and edit things, use it for creative purposes to fit the story. How careful were you with Bram’s diaries when you were using them for the creation of the prequel and the sequel? How close are those two books to what Bram was writing in his diaries?

DS: Well, in 2012 the Journal was actually published… We use the terms “diary” and “journal” interchangeably right now… Technically, a diary is sort of like “this day I did this and invited this person for lunch and so on…”, this was actually a journal that I found, and it consisted of thoughts, observations, feelings, things Bram wanted to jot down, things he kept for his stories and so on. There’s only a reference to a diary. So that was number one, that journal was published as Bram Stoker’s Lost Journal. However, when I decided to take that and fictionalize it and use exactly as you say – this became a very useful tool, because in some cases there were actual situations and interactions with people that I saw and said “Ah, yes, I can use this in the fictional story”. And make some small alterations to it along the way. Which many of us writers, like yourself, do as well. You know, you say that things in the story are based, loosely or lightly, on things that really did happen. And I can make a general statement, Lisa, and just say that in Dracul about 70 percent of the things that you see happen in that story were real events. They came out of either that Lost Journal or newspapers that I found from that time. The rest 30 percent – is pure fictionalized adaptation. The sequel Dracula the Un-dead – I didn’t have the Journal at the time so there was much more speculation. We had the Dracula Notes and I had access to the typescript but not the Journal, so that’s why in the prequel there’s a lot more things that happened to Bram Stoker, stories about Bram Stoker growing up and him writing Dracula as a warning to the world. Because that’s what I gathered from that first-hand source material.

LM: Got it, interesting. Now, in movies and many theatrical productions and musicals that have been created about Dracula or dedicated to Dracula, in them the image of Dracula very often is different from what we read in Bram Stoker’s novel. Even though, I would say that the image of a villain who was not described in detail really, was just “the villain Dracula”. Now, during the time that passed, Dracula slowly transformed into this ever-youthful, intelligent dissident who is tired of life. Not to mention that he became extremely attractive. Do you think that this transformation of the original image of Dracula would make Bram upset? What would Bram think of that socialization of the image of Dracula?

DS: You’re absolutely right that this happened, and I’ll just give you a small take on what I think, why that happened. Bram’s Dracula is only described twice in the novel, and he looked like, as Bram described him, and Bram was into phrenology – he was really into physical characteristics of somebody’s facial and other features, he called Dracula “a criminal mind” and his description was of a “criminal” of the time, that’s what people thought. So, Dracula is not a particularly attractive man. But after Bram died in 1912, Dracula hit the stage when Florence Stoker worked with Hamilton Deane and then later with John Balderston to bring Dracula to the stage. It was common that your leading men and women were physically attractive. And, in my opinion, if according to the book, Dracula was this horrible gnarly, gross looking criminal, people would walk out of the theater. And you know this, it’s true till this day. You know, great makeup and so on. But you want to have, in those days, somebody who is physically attractive, who looks like a debonair Eastern European aristocrat-turned-vampire. And then, later on, overtime, we had Bella Lugosi, Frank Langella, Christopher Lee on film and all the others. Then a couple of years ago, we were presented with these hot looking teenagers in Twilight and True Blood, Vampire Diaries, you know – all these people look like they came off the runway. No resemblance to Bram Stoker’s vampire, but what they were doing was modernizing this revenant from the grave to become something that is almost scarier – now it’s somebody among us, who appears like us, or super attractive, that could be one of us, or the girl next door, or the hot model out of a catalog. They could be the vampire that gets you. No advanced warning, because they don’t look like the traditional gross-looking monster. So, that’s my take. What would Bram think? I think he would have thought it was brilliant. Because, as a theater manager, what’s not to like? He and Irving did their own adaptations of stage plays to make them appropriate for their audiences. First of all, he would have been proud – imagine a long run of Dracula on stage, even 125 years later. I love to see when people like you, write their own stage plays and all – what inspired you? What is your take? What reimagining you have on this? This is what keeps the story fresh and alive even though it’s 125 years after the original book was published.

LM: Absolutely. So who, from all the actors that you’ve seen play Dracula, who do you think portrayed Dracula the best?

DS: That’s a loaded and complicated question. I always shy away from “the best”. But I’ll give you the list of favorites – and there’s an explanation to it – the period in which these actors and actresses played. Obviously, there’s a disadvantage when you look at Bella Lugosi, who did a heck of a great job and he was fantastic as the first Dracula in film – he wasn’t speaking the English language, he had to speak phonetically, but that was powerful, and he had that great look. But I also love Christopher Lee, who had the advantage of being able to have some fangs and blood which Lugosi didn’t have. So, that was cool. His stage presence was awesome. I liked Frank Langella, I thought he was great. He was one of those more romantic Draculas. I also love in the 79 film – the way he died, on that hook on the ship, with the sunlight out – it was super powerful! But I also like Gary Oldman. He, however, had the benefit of some very modern costumes and makeup. So, those are my big ones. Top of the list. But there are so many that have done great stuff, but are sort of under the radar – Gerard Butler, Leslie Nielsen, George Hamilton, John Carradine. So many have played – Jack Palance… They all did wonderful jobs, it makes it hard to narrow it down. That’s why I just stay away from that. But you got my top list anyway.

LM: Good. Well, kind of tapping into the subject we’ve discussed just before I asked this question – with all the different approaches to the character of Dracula, the image of Dracula and how he changes, how you mentioned that Bram would actually be very happy about the fact that those changes are happening. Could you ever imagine a woman playing the character of Dracula?

DS: That would not bother me at all. We’ve had some really kickass vampire women in film – in the Underworld series Kate Beckinsale was amazing. When you also think of bringing countess Elizabeth Bathory into the picture, and here I’m kind of tapping myself on the back a little, as I did in Dracula the Un-dead. She has been depicted in film. So, yes. There would not be any problem, and people have done it on stage. When people do these gender swaps and things. As long as it is made believable, as long as they do a good job of giving you a backstory – not just for the sake of “oh, we’re going to shock everybody and make it a female” but let’s make it believable and do a good job – I’m all for it. Absolutely.

LM: Are there any plans on bringing the sequel or the prequel, I believe you did mention the prequel before, to the TV screens and to turn it into the movie?

DS: The Paramount has purchased the option to Dracul. And we’re crossing our fingers if they continue to keep the option or if somebody else will – there are no actual firm plans for the moment. But there’s a lot of interest, I can say that. And I also want to mention, that I think Dracul would make for a real cool series. I mean, if it became a feature film, I wouldn’t be upset. Now we sit back and let the agents deal with agents and we’ll see what happens.

LM: That’s mainly concerning the prequel. What about the sequel? Would the sequel be turned into a movie possibly?

DS: It’s all possible. There was some interest when the book first came out. For whatever reason, that interest went away. But, as long as the book and the options are available, it could happen. I am not a movie guy, I’m not even a stage person, like yourself. I don’t quite understand that world and how all of those things work or how the powers that be look at literature and say: “Ah, the time is right”. This book was an international bestseller, went to top 21 on the New York Times List. I know there’s a bunch more to that, how those decisions must have to be made. So, they’re available. If anyone’s thinking of turning it into a stage play or series and feature films – give me a call, I’ll connect you to the agents and they’ll let you know.

LM: I feel like it’s always very interesting when it comes to sequels, specifically, how people react to a sequel to the famous and beloved stories. I don’t know if you are acquainted with this one, but the sequel to Dracula made me think of this other sequel which came out in 1999 and that was a sequel to The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux, written by Frederick Forsyth. I happened to have read the sequel to The Phantom of the Opera and the sequel to Dracula – Dracula the Un-dead pretty much at the same time. Even though, the Phantom of Manhattan came out in 1999. There is quite a break between these two. But what I found very interesting was that there were some similarities in the two sequels. In Dracula the Un-dead, Mina and Dracula reunite, Dracula is not dead, Dracula is the father of Mina’s son, and, at the end, Dracula is on his way to the U.S. Kind of similar things are happening in The Phantom of Manhattan – Phantom gets reunited with Christine, her son is Phantom’s son, and they find each other in Manhattan.

DS: Wow! I did not collaborate with Mr. Forsyth. So that is an interesting irony and you’re the common denominator who’s pointed it out. That’s incredible and, obviously, he wrote it in 1999 and we didn’t get ours until 2009. And somebody could say that we stole some of their thunder, but that’s the first time I’ve heard of it. There you go.

LM: It’s just interesting to see how the story develops in a similar fashion. And that we all end up in the U.S. I found that quite fantastic. Your story in the sequel, with Dracula the Un-dead is based on the notes and journals by Bram. The finale of it is still an open finale – we don’t see that Dracula is dead. He is not dead, he’s still around. I don’t really want to give away too much and tell the readers what happens in the book…

DS: It’s as ambiguous as Bram Stoker left Dracula. Did he really die? We know there was some climactic battle at the end, which is no spoiler. But the door is open. As you should do in a book like this one. Just in case someone says “Oh, why don’t we write an adequate continuation?” and the sequel. A-la Star Wars many times over. We didn’t want to have a definitive ending, much like Bram Stoker didn’t want to end his wonderful novel. We decided to keep the door open for more possibilities and keep you guessing. So we’ll just keep people thinking that they should just go and buy this book and read it and figure out what the heck we’ve been talking about. Because that was our intention – to keep that possibility alive.

LM: Keep the cliffhanger! When it comes to the sequel, again thinking of that parallel that I happened to make with The Phantom of Manhattan and Dracula the Un-Dead, Andrew Lloyd Webber wrote the musical sequel – Love Never Dies based on Forsyth’s sequel – and when that musical hit the stage, a lot of spectators were not very happy to see Phantom come back to life and see that continuation of the story. What do you think about Dracula the Un-dead – if it gets turned into a musical, a movie, a stage production – how do you think people are going to react to the story of Dracula continuing in such way?

DS: That’s the crystal ball that I don’t own. But I will say this, when the novel came out, about half the people that wrote reviews on Amazon and GoodReads – were thrilled that the story continued, and they got to reconnect with the characters that they have grown to love and fear. But the other half were very wary and some even were absolutely against “messing with a good thing”, so to speak. They didn’t like that Ian and I decided not to write in an epistolary style, so, according to them – we had no business of writing a sequel to Dracula because it wasn’t even written in the same style as the first book. Quite honestly, we felt that the epistolary style was difficult to read for people, it was also difficult for us to write, we were not seasoned and strong enough writers to do so. So we kept it simple and in more of a prose, narrative style. However, I took that to heart and when it was time to write to prequel with J.D. Barker, we decided to go back, not exactly strictly following the source style, we took some liberties, but used that style. What’s interesting is, since the prequel has come out, I have noticed a dramatic change and I don’t live and breathe by reading my reviews on Amazon – otherwise one would go crazy, but it really is quite interesting that many people have gone back to Dracula the Un-dead, either because they read Dracul and liked it or because they decided to give it another shot. The number of stars and positive reviews has increased. It’s not always a permanent thing, people get knee jerk reactions when they read classic stories or rather the continuations of classics that meant a lot to them and they might initially hate the way that somebody portrayed them but then maybe they warmed up to them after a while. So I’m glad they are doing that because I think it’s a fun and easy read. It’s an easier book to read than Dracula. But when it comes to “will it ever go on stage” or on screen, or become a musical – how would people react? I would imagine the same way – there’s a lot of Dracula adaptations – operas and films, musicals, that people give birth to, reimagining, to keep it fresh and different. So hopefully, that would be the case if any of the two books I’ve co-authored get morphed into the performing arts.

LM: I would be very excited to see a movie version of either one of them – prequel, sequel. So hopefully it happens. Now, do you have any famous actors in mind to play the main characters in a movie? For Bram Stoker and Dracula?

DS: You would not believe how many times I get asked that question – and I’m terrible at names. I love watching all kinds of shows and just the other day, at one of the talks out here in Burbank, people who are very focused on names of actors and actresses said: “Oh, who do you think should play Bram?”. There was an HBO series called The Knick about the Knickerbocker Hospital here in New York at the turn of the century – I love it, Clive Owen was awesome in it, he was this doctor and there was an Irish American policeman who played a significant role – and he would be a perfect Bram Stoker. His name is Chris, but I don’t remember his last name… Chris Sullivan? And, I think Clive Owen or Jeremy Irons would be really good as Dracula. But there’s some fresh blood coming up – I liked Claes Bang who was in the BBC Netflix version – that was cool. I have given you a couple of names.

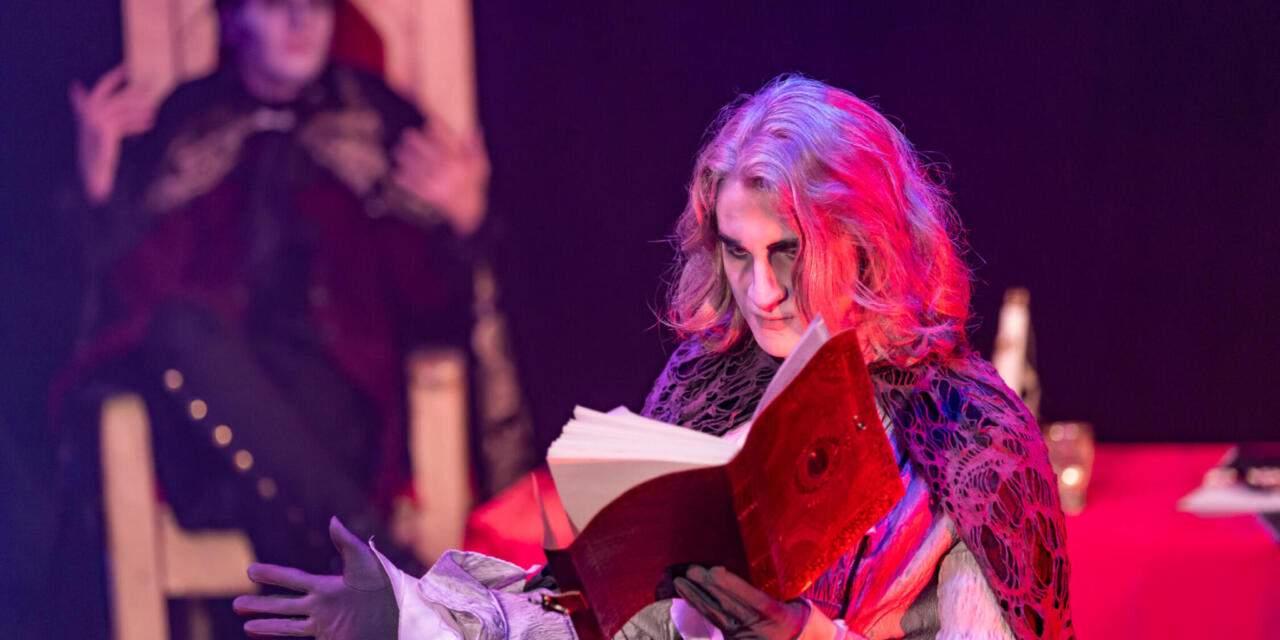

“Dracula: Finding of a Shadow” PC: Shane Maritch.

LM: It’s too bad you can’t attend our premiere of Dracula: Finding of Shadow here in New York in person. Because, you never know, maybe you would have liked our Dracula and our Bram Stoker? But we are definitely going to share your work with our audiences, we are going to tell them about the sequel and the prequel and once the show is done, we shall send you a video.

DS: I can’t wait! It’s an honor, really, to be chatting with you and to see your enthusiasm and your research into my great grand-uncle’s work, as well as my work. And just to see it come out on stage. You know, the timing couldn’t be worse for us, Lisa, unfortunately, to all the people reading our interview – this is just a jam-packed schedule with the 125th anniversary of Dracula this year. I just hope that maybe your play gets picked up and it moves on and I would be able to see it in person. I’d love to watch the video and I will be recording a nice little video for you to put at the end of the show. Sort of, giving the audience a little connection of the man that was the impetus to all this, to Bram Stoker. Thank you so much for thinking of me and my family. And best of luck with your creative work! Because it’s people like you that keep the story alive. Your interest, your talent, creativity, keeping Bram Stoker’s work alive. That’s what it’s all about. So, here’s to you and your work!

LM: Thank you, Dacre! I believe in signs, and I think everything happens in life for a reason, so we met this year, which is the 125th anniversary of Dracula. And I think, that’s fantastic! So far, for our next step, I do suggest another interview. For you to have. But this time, I think you should be interviewing Dracula.

DS: Haha, yes! I would like to ask him some questions. I’ll have to do a little prep work.

LM: We can arrange that! And maybe we’ll call it Dracula’s Guest…! I think that applies.

In turn, we would like to invite our readers to come to the show at the Gene Frankel Theatre, where from October 19th until October 30th, Wednesday through Sunday, you will be able to meet with an intelligent Dracula, charming vampiresses, insidious Alucard – the Count’s shadow, and other vampires.

Tickets can be purchased at: https://www.genefrankeltheatre.com/dracula-finding-a-of-a-shadow—the-onomatopoeia-theater-company-in-collaboration-with-monli-international-company-llc.html

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lisa Monde.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.