On the final day of the Prague Quadrennial, I decided to explore the roots of the Czech theatre tradition. I took the subway, then another subway to the end of the line, then a bus through a big-box retail zone (Ikea land) before I arrived at what looked like a small village on the outskirts of Prague. I was in Chvaly, and its centerpiece was the fifteenth-century Chvalský zámek, the Chval Palace. The palace is a lovely destination in its own right, sitting off to the side of a nice square with a hotel and restaurants. I recommend Curry Tikka which serves the best Indian food I’ve had in the Czech Republic. But I wasn’t there for the palak paneer. I was there for the puppets.

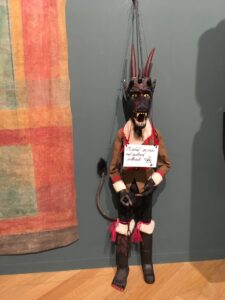

The sign says, “You may carefully touch me.” Oh and I did. Photo by Abigail Weil.

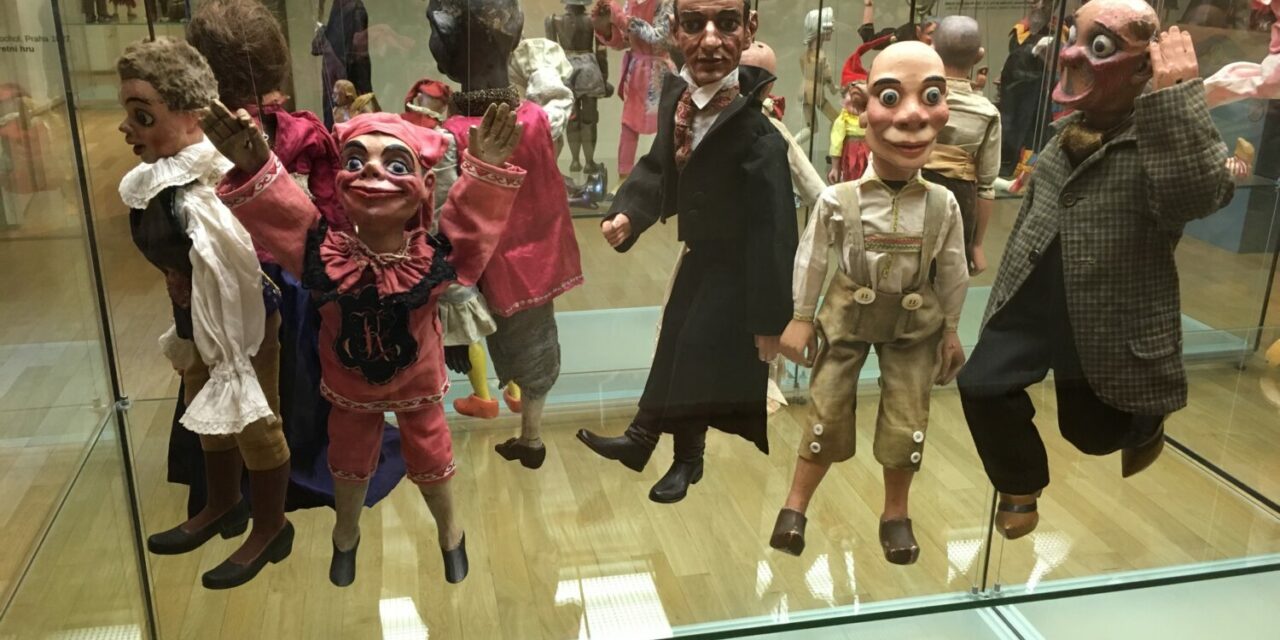

“Umění loutky” – “The Art of Puppets” – is a temporary exhibition at the Chval Palace, and boy am I glad I caught it. The exhibition is on loan from the private collection of Marie and Pavel Jirásek, who have lovingly assembled examples from this art-form which is rightly placed on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. In the exhibit, you can see not just centuries’ worth of puppets, but backdrops and whole puppet theater-boxes too. I was one of the only solo adults checking out the exhibit that day. The other was a bemohawked punk. Everybody else was children with their adult escorts. And everybody was having an absolute ball.

Puppetry has a long and important history in Czech culture, which the exhibition does a fantastic job of illustrating, harmoniously in line with the theme for this year’s PQ: Imagination, Transformation, Memory. The emblematic Czech puppets are marionettes made from the wood of the linden tree, the Czech national tree whose leaves are exceptionally fragrant this time of year. The tradition began at the end of the eighteenth century with traveling puppet theatres, families who journeyed in caravans to perform in villages. Not children’s theatre, the companies performed repertoire works in the European mode, like Shakespeare and Faust. These puppet theatres are important not only for the incredible craftsmanship of the marionettes but also for the way they contributed to the Czech National Awakening, a project of creating a cultural renaissance in line with Romantic-era notions of national identity. Because the puppets, unlike the actors on the fine stages of Habsburg-controlled Prague, spoke Czech. During an era German was still the language of state and Czech was more or less confined to villages, these puppeteers forged a path for artistic creation and coded self-expression.

In red and blue, a Kašpárek by an unknown artist in eastern Bohemia in the 1920s. Photo by Abigail Weil.

This may be why one of the most iconic characters in Czech puppet theatre is a bit of a cheeky devil. Kašpárek, a Czech version of the German Kasperle, is ultimately a sort of Pulcinella character, a sly, often violent, cheerful scamp. (He also has cousins in France and England – Guígnol and Punch). The exhibit has a lot of different versions of Kašpárek, some from the seminal Kopecký family, some examples from the twentieth century. While Kašpárek’s appearance is open to interpretation, the tradition of a beloved, ill-behaved anti-hero has held strong. The good soldier Švejk, for example, is a sort of literary modernist Kašpárek.

The exhibit traces the history of Czech puppetry from its Renaissance origins through the First Czechoslovak Republic. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Czech puppetry began to attract international attention and in 1929, Prague became the home of UNIMA, the International Puppeteers Union. UNIMA celebrated its ninetieth birthday just last week, at the PQ. Some of the greatest Czech filmmakers came out of the school of puppetry, including Jiří Trnka, who is represented in this exhibition, and claymation animator Jan Švankmajer.

The first two from the left are Spejbl and Hurvínek. Photo by Abigail Weil.

Sure, we have other options now. We can go hear actors speak Czech onstage at the National Theatre. We can watch movies with CGI and 3D animation. And yet puppetry is still a beloved artform. In 2010 Jan Svěrák, of Kolya fame, made the lovely film Kuky se vraci, Kuky comes back. It tells the Toy Story-type story of a well-loved teddy bear making his way back to his boy. It was released on HBO as Kooky, give it a watch. On the street where I live in Prague’s Dejvice neighborhood is the Divadlo Špejdla a Hurvínka, the Theatre of Špebl and Hurvínek. They’re a bug-eyed puppet duo created by Josef Skupa in the 1930s and yes, you can see them at the Chvaly Castle. Even when the theater is closed, you can see people outside posing with the life-sized bronze statues of the pair. DAMU even has a department of Alternative and Puppet Theatre.

The first time I came to Prague, I went to the National Marionette Theatre to see a performance of Don Giovanni. Mozart wrote the opera in Prague and conducted himself at the German-language Estates Theatre. Mozart conducts in the puppet version too, but they give him a personality like Kašpárek. (Meanwhile, they somehow claimed the domain name mozart.cz.) Now I know it’s a tourist trap, and Don Giovanni is the only thing they do. But back then, I was twenty-two, and it was my first time in Europe. I had a very dilettantish interest in Czech culture, but somehow, I knew that puppets were a part of it. I begged my travel-partners to come with me but one opted to go to the equally touristic Museum of Communism and the other, and I’m still mad about this, sat in McDonald’s and read a book. I began my own long tradition that night, of taking myself on dates to the theatre.

Another Czech tradition – underground theatre. Photo by Abigail Weil.

The real proof of puppetry’s vitality was there in the basement of the Chval Palace. Museums do what they can to encourage their visitors’ participation, and with the “Art of Puppets” exhibit, they nailed it. Against the walls were more classic puppets, now displayed in their carrying cases so you could imagine being a part of one of these marionette caravans. And taking up all the space in the galleries were little puppet theatres. You could make your own out of paper and sticks or learn how to contort your fingers into shadow puppets. You could work with a marionette, which is really freakin hard. Or you could do what most of the kids were doing – climbing in the booth and performing wild improvisations for their parents. From the audience’s vantage point, you could only see their puppets, and often their fumbling little hands. Yet you knew that back there, crouching behind the booth, they were smiling.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.