Pilgrimages have long served as expressions of both collective and individual faith, as well as acts of self-sacrifice, typically involving arduous journeys and symbolic offerings. Whether they are spiritual or popular, these public displays of devotion are by definition theatrical and rich in tradition. Although participants in such rituals tend to focus on a destination, most undergo transformative experiences in a process entailing personal challenges, self-reflection, and exposure to new cultures, customs, and diverse fellow pilgrims. It is precisely the multifaceted nature of such encounters that provides the framework for Maria Marull’s stage triumph and opera prima, La Pilarcita.

La Pilarcita premiered in Buenos Aires in 2015 at El Camarín de las Musas, under the direction of Marull, and continues to run this year for a fourth season at this iconic venue for independent theater. The play was also successfully staged last fall in Madrid at the Teatro Lara, under the direction of Chema Tena. Marull sets La Pilarcita in a small, rural town in northern Argentina during the feast of the eponymous patron “saint.” It is during this annual celebration when outsiders flock to the town to partake in its carnivalesque festivities, that the municipality comes alive, compelling locals and visitors alike to navigate conflicting values, norms, and traditions. According to local legend, La Pilarcita was a little girl from the town of Concepción del Yaguareté Corá (province of Corrientes) who died tragically while traveling with her family in an ox-drawn cart. During the journey, her favorite doll fell to the ground, and when Pilar jumped down to retrieve it she was run over by the cart. Ever since this fatal event, each year on Pilar’s birthday people from all over the country return to the site of the accident, where a shrine has remained, bringing offerings of home-made dolls in hopes of receiving divine favor.

Production photo from the Buenos Aires production of La Pilarcita, by Maria Marull. Photographer: Mariano Asseff

The dramatic action of La Pilarcita takes place at the modest home of Celina, whose family rents a room to out-of-town visitors coming for the celebration of the popular saint. All the action takes place on the patio, where a simple set consists of a table and chairs, a fan, an inflatable children’s pool, the window and door of a guest room, and an open doorway to the kitchen. Prominently centered behind the furniture stands a humble altar dedicated to La Pilarcita. Finally, bed sheets hung out to dry at stage left double as curtains through which characters enter and exit.

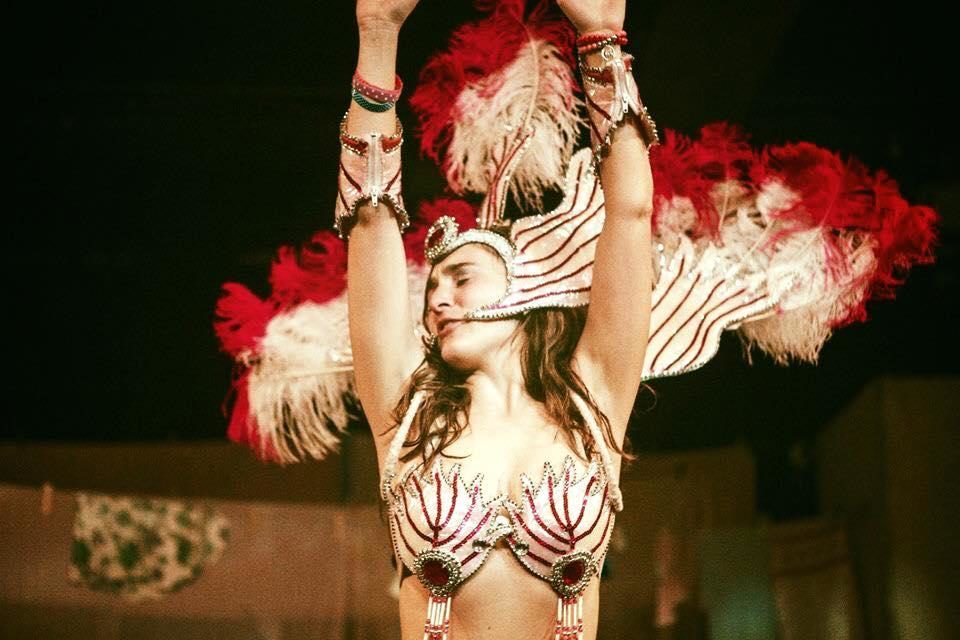

La Pilarcita features working-class protagonists who must confront middle to upper-middle class characters that descend upon their world. Celina is a quiet, hardworking teenager who spends her time studying and accommodating the annual guests. She aspires to attend medical school and also hopes to win the love of Rubencito, who has been seen lately with a new girlfriend. Celina is joined by her good friend Celeste, who has come to help her with the guests and household chores so that Celina can focus on her studies. Celeste is a rambunctious adolescent who sells her hand-made dolls to tourists seeking miracles during the feast of La Pilarcita. At the beginning of the play, she is also preparing a sexy costume for the comparsa dance competition segment of the festival. She plans to wear high heels and a bikini adorned with brightly colored sequins and feathers, similar to the iconic regalia worn by women in Rio de Janeiro during Carnival. Celeste dreams of leaving the town someday for an exciting, more fulfilling life in a big city. Throughout the play, she suffers from the oppressive summer heat, a metaphor for the stagnant conditions, limited opportunities, and traditional values that define life in her town.

Production photo from the Buenos Aires production of La Pilarcita, by Maria Marull. Photographer: Mariano Asseff

Celina and Celeste are also accompanied by Celina’s brother Hernán, who has returned home for the feast of the little saint, intending to compete in the new songwriter contest. Hernán appears at pivotal moments, including scene transitions, in a role reminiscent of a strolling troubadour. He sings and plays the guitar, his lyrical interludes informing the audience of key background information regarding La Pilarcita as well as the various characters. Furthermore, after the action comes to a close, his melodies serve as a musical epilogue both revealing and reflecting on the fate of each character. Thus, through the figure of Hernán, Marull integrates a pseudo-narrator while simultaneously weaving in a medieval tradition as time-honored as pilgrimage itself.

Following Hernán’s arrival, and that of Celina’s house guests on the eve of the feast day, several dramatic conflicts erupt. This discord punctuates the clash of values, traditions, and gender roles marked not only by contrasting socio-economic classes but also by the urban and rural attributes of the respective groups. Selva and Horacio, her married lover, have just arrived from the city of Santa Fe. It is their first pilgrimage; they are not well informed of the customary rituals, and it is not clear what, exactly, they hope to gain. For instance, is the trip merely intended as a romantic getaway to some enchanting locale with quaint traditions? Did Selva come to request divine intervention regarding Horacio’s mysterious illness? Or is she secretly hoping that La Pilarcita will intervene persuading her lover to leave his wife? Curiously, the influential Horacio never actually appears on stage, despite his strong effect on Selva and his stance as the motive for their pilgrimage. Paradoxically, the focus is on Selva, whose name (“Jungle”) seems ironic given her initial presentation as the stylish, metropolitan woman. Yet, even at her introduction, there are conflicting signs in this regard. She arrives wearing an animal-print top with her tight jeans and designer heels, and through her pervasively rude, arrogant behavior, she does ultimately live up to her name’s intimation that she may be “uncivilized.” Her self-centered, true character reveals itself largely through a continual disregard for others. She also complains repeatedly about the lodging conditions, and she will only consume mineral water, fresh squeezed orange juice, artificial sweetener, low-fat cheese, and whole wheat bread, none of which are available at Celina’s home.

Production photo from the Buenos Aires production of La Pilarcita, by Maria Marull. Photographer: Mariano Asseff

The rural-versus-urban binary opposition in La Pilarcita is particularly emphasized during a late-night conversation between Celeste and Selva in which the former inquires with great curiosity about daily life in Santa Fe. Celeste is fascinated by the high-rise buildings, modern conveniences, and the general hustle-bustle of big cities. It is evident that she feels suffocated in her isolated town. She underscores its lifelessness, which is only disrupted a few days each year through the explosive revelry that marks the culmination of the solemn pilgrimage.

On the feast day of La Pilarcita, all of the women in Marull’s play must confront a disappointing reality, reevaluate their dreams and expectations, and accept the fact that the cherished saint does not accommodate all requests. The comparsa competition is fierce among the rival neighborhood groups, and Celeste is attacked by an opposing dance team on the night of her performance. She returns home broken, covered in mud, her dazzling costume ruined. Similarly, after waiting in long lines with the doll that Celeste made for her, Selva collapses in the sweltering heat, incapable of expressing her petition just as she reaches the statue of the saint. Nevertheless, that night she indulges with the locals, dancing wildly and drinking herself into a stupor, and is spotted in an amorous encounter with Rubencito. Sadly, violence, cut-throat competition, debauchery, and greed now dominate and taint the traditionally sacred ritual in honor of La Pilarcita.

Production photo from the Buenos Aires production of La Pilarcita, by Maria Marull. Photographer: Mariano Asseff

The decadent festivities leave Marull’s female characters deeply disillusioned. Infinitely worse, their despair culminates in shock and devastation when Horacio dies suddenly that same night. Nevertheless, although the joyful occasion has been shattered for the protagonists, all hope is not lost. This is because the pilgrimage ultimately results in a personal liberation for both Celeste and Selva. With Horacio’s death, Selva is no longer trapped in a hopeless relationship, and Celeste will accompany her back to Santa Fe where she can start a new chapter in her own life. Moreover, Celeste’s decision to bring decorative pots for the plants that they will cultivate at Selva’s apartment suggests metaphorically that both women will embark on a new phase of personal growth in their lives.

In contrast to Celeste’s departure on an urban path of independence, Celina will pursue her studies and day-to-day life in the pueblo. With the beautiful doll that Celeste leaves her, it is evident that she will continue her devotion to La Pilarcita. Additionally, through her role as hostess to the out-of-town guests, Celina will continue to serve as a personal, social, and spiritual guide, sharing a wholesome way of life and an endearing, century-old tradition with those in search of a miracle.

From the Buenos Aires production of La Pilarcita, by Maria Marull. Photographer: Mariano Asseff

La Pilarcita offers a heart-warming tale spun with an innovative blend of humor, realism, legend, music, and a plurality of perspectives. Together these elements fuel the distinctive magic that characterizes María Marull’s theater. The play was inspired by collective faith and traditions flourishing in response to a tragedy. In 1917 a little girl named Pilar Zaracho was in fact killed in the province of Corrientes when she jumped off the family cart to retrieve her beloved doll. To this day, people visit the shrine at her roadside burial site leaving gifts of hand-crafted dolls. Through the context of this popular pilgrimage, María Marull highlights the role that customs play in our lives and how even in the face of conflict, beliefs, rituals, and values can unite a diverse range of people on a journey of self-discovery.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Susan Berardini.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.