On March 3 and 4 2018, the Arcola Theatre in East London presented Global Queer Plays, a series of rehearsed readings of LGBTQ+ plays in translation or from the parts of the English-speaking world less represented on UK stages. In this personal reflection on the event, translator and member of the festival’s team William Gregory describes the context of the festival, its story, and his hopes for its future.

The Arcola Queer Collective was established in 2014. As part of the community engagement activities of the Arcola Theatre in the east London borough of Hackney, it seeks to involve local LGBTQ+ people–be they professional theatre-makers or not–in theatre and performance, and to fill some of the gap left in the capital’s theatre firmament by the closures decades ago of queer, activist theatre companies such as Gay Sweatshop.

It was in this spirit of honoring queer theatre history–and tying in with the 50th anniversary of the partial legalization of sex between men in England in 1967–that the collective restaged a treasure trove of lost LGBTQ+ plays in 2017, with the help of Unfinished Histories, a dedicated archive of alternative theatre. Among these under-acknowledged gems was The Drag, a glamorous and sexy romp through the Hollywood drag ball scene of the 1920s, penned by none other than Mae West, which, astonishingly, had never been produced in the UK before. Call it coincidence, but a few short months later, the National Theatre of Great Britain also staged a rehearsed reading of the play as part of its own 1967 anniversary celebrations.

In response to the National’s programming of this and other works to mark 50 years since the passing of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, the UK broadsheet The Daily Telegraph published a commemoration of its own, entitled The Five Gay Plays That Changed The World. Readers of this, a global theatre website, will notice something remarkable about that list: all five plays, from The Drag in 1927 to Wig Out in 2008, were all written originally in English, and are from either the UK or the United States. And yet they changed “the world.”

It only takes the shortest of hops over the English Channel to find an alternative view. Written in 1990, French playwright Jean-Luc Lagarce’s Only The End Of The World tells the story of one man’s trip back home to break the news of his illness and impending death to his family. His arrival, however, only revives the tensions and failures of communication that have long dogged his relationship with his kin, and he ends his visit not having said what he planned. With a place in the repertoire of the Comédie Française, Only The End Of The World won the 2007 Molière Award for best play, was placed on the curriculum for the French school-leaving certificate the baccalauréat, has been translated into several languages and has been made twice into a film, most recently in a 2016 Canadian co-production starring Marion Cotillard.

The 2007 Comédie Française production of Only The End Of The World by Jean-Luc Lagarce (Photo © Brigitte Enguerand/Divergence)

The growth of the Arcola Queer Collective coincides with something of a flourishing of LGBTQ+ theatre on the London stage. In Islington, the King’s Head theatre’s annual season of queer plays has included rediscovered classics such as the 1960s farce Spitting Image by Colin Spencer or Paul Boakye’s Boy With Beer, a tale of being black and gay in 1980s Brixton. Its production of The Strangers In Between by Australian playwright Tommy Murphy transferred in 2018 to the West End’s Trafalgar Studios. The same success–and an Olivier Award–was enjoyed by Rotterdam, Jon Brittain’s play originally produced at Theatre 503, a love story with a trans man as its protagonist. Above the Stag, London’s dedicated LGBTQ+ theatre is set to move to new, larger premises in 2018. The National Theatre’s 2017 revival of Tony Kushner’s masterpiece Angels In America came hot on the heels of the UK premiere of his The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide To Socialism And Capitalism With A Key To The Scriptures at the Hampstead Theatre a year earlier, and is unofficially followed at the Young Vic this year by Matthew López’s The Inheritance, a New York two-parter exploring life amongst today’s queer generation. And returning to gay theatre history, the Donmar Warehouse and Park theatres have, respectively, recently revived Peter Gill’s The York Realist, set in 1960s Yorkshire, and Mart Crowley’s New-York-set The Boys In The Band.

All this is to be celebrated. But, like the Telegraph’s gay plays that change the world, they all have one thing in common: the Anglosphere. And even then, only part of it. (And even then, a remarkably cis-gendered, gay, male part.)

Meanwhile, the London stage has in recent years done more to embrace the international. The Royal Court theatre’s 2017 season included three plays in translation (from Syria, Chile, and Ukraine), two of which were staged in its main space, the Jerwood Theatre Downstairs. The Orange Tree in Richmond saw productions of plays from Germany and the Netherlands in 2017; the Lyric Hammersmith and Park theatres both produced German plays that same year. In Notting Hill, the Gate Theatre has returned to its international roots with work in its new season from Portugal, Germany, and France. The Southwark Playhouse recently staged a new Russian play; the Young Vic adapted Lorca’s Yerma to great acclaim, and re-imaginings of Chekhov and Ibsen continue to abound, while French writer Florian Zeller’s plays all receive productions in London just as soon as his translator Christopher Hampton can render them into English.

55 Shades Of Gay by Jeton Neziraj at the Arcola Global Queer Plays festival (Photo (c) Ali Wright)

But plays that are both queer and global? Perhaps an intersection too far for producers. A play in translation has enough hurdles to leap before it can get programmed on the London stage, without having the additional factor of appealing to another perceived niche market. And if a queer story is going to be told, perhaps it is deemed more appropriate for an English-language playwright to tell it, leaving the occasional play in translation to tell other kinds of stories that open audiences to the international in a different way. One can debate the rights and wrong of this. But even with this said, it is striking that even queer characters, let alone ones central to the story, are rare in the plays in translation produced in London’s theatres.

The only exceptions that spring to mind are recent productions of Alberto Conejero’s The Dark Stone and Guillém Cluá’s The Swallow, translated by Tim Gutteridge, at the Cervantes Theatre in London. It is perhaps no coincidence that these plays both feature at a theatre whose repertoire–as its name suggests–is exclusively made up of work by Spanish and Latin American playwrights, and who can therefore fit in a wide range of themes and plays, including one or two LGBTQ+ stories alongside other new Spanish plays or revivals of canonical works such as Lorca’s The House Of Bernarda Alba or Blood Wedding. Meanwhile, another specialist organization, the CASA Festival of Latin American theatre, also produced a play with a gay protagonist in 2017: Uruguayan playwright Sergio Blanco’s Thebes Land, translated by Daniel Goldman.

Outside of these dedicated, language-focussed spaces, however, international theatre in London is strangely heteronormative. And our queer theatre is strangely Anglophone.

As a translator of plays, an adopted Londoner, and a member of the LGBTQ+ community, I had for a long time wondered what other stories were out there, and how one might be able to make space for them on the stages of our city. We translators have little influence over what gets programmed, generally translating plays that others have commissioned. The occasional LGBTQ+ play in translation that I had tried to champion had rarely succeeded in finding a production or even a reading. But nevertheless, I was convinced that there must be work by queer writers or on queer themes sitting on hard drives or in drawers all over the world and just waiting for an audience.

It was when I saw The Drag in 2017 and learned more about the work of the Arcola Queer Collective–and especially its open-minded and democratic approach to programming–that I saw a chance. A few months later I was in a rehearsal room at the Arcola pitching an idea for a series of readings of LGBTQ+ plays from around the world to the other members of the collective. The premise was simple: ask playwrights and translators from anywhere in the world to submit plays in translation or from under-represented parts of the English-speaking world that told stories by and about queer people globally. We would not commission new plays; we would give space to the stories already being told but that London audiences had not yet seen. A few weeks after that, I received the great news that the pitch had been successful: Global Queer Plays was going ahead.

What followed surpassed all my expectations.

Winters Animals by Santiago Loza, produced in 2017 at The Cherry Arts, Ithaca NY (Photo (c) The Cherry Arts)

In the short month during which our submission window was open, we received over 100 entries. They came from every continent and were translated from many languages. Some plays were by playwrights famous at home but little heard of in English-language circles; some were new works by emerging writers. Some plays had been performed at home dozens of times, been published and won national awards; some had been written in exile and could not envisage a staging in the writer’s country of origin. We received hard-hitting pieces on the plight of queer people under homophobic regimes; lyrical pieces exploring queerness from a more abstract perspective; out-and-out comedies celebrating queer life in riotous fashion, and everything in between. Selecting just seven plays was no easy task. Even this early on, it became clear that there was a wealth of material worldwide and that we may need more than one festival to do it all justice.

Programmed over the weekend of March 3-4 2018, our seven final plays were as follows: the above-mentioned Only The End Of The World, by Jean-Luc Lagarce, translated from French by Lucie Tiberghien. It was astonishing to think that a play so successful, from one of our nearest neighboring countries, had had so little exposure in the English-speaking world, especially given the success in London of other French playwrights in recent years. As the one play from Western Europe, it was striking how it spoke to the queer community’s lingering inability to speak openly about ourselves in a supposedly more liberal society.

From Kosovo, Jeton Neziraj’s 55 Shades Of Gay, translated from Albanian by Alexandra Channer. This irreverent, provocative comedy, staged originally in the burlesque style when it premiered in Pristina in 2017, sets the EU on a collision course with the locals of a provincial Kosovar town when an Italian official’s insistence that he be allowed to marry his boyfriend–and the local mayor’s refusal to grant a licence–puts the long-awaited building of an EU-funded condom factory and Kosovo’s hopes for a future at the table in Brussels at risk. Penned by the prolific former artistic director of the National Theatre of Kosovo, this view of international intervention from the recipient’s perspective treats the locals’ homophobic bigotry and the international community’s patronizing attitudes with equal quantities of ridicule.

The 2017 original production of 55 Shades Of Gay by Qendra Media, Kosovo (Photo (c) Jetmir Idrizi)

Born in Kuwait to Egyptian parents, US-based Mariam Bazeed shares a personal memoir in Peace Camp Org. Hilarious and heartbreaking by turns, Bazeed takes us on the journey of the young Mariam from her oppressive yet comical life at home with her parents to the increasingly absurd setting of a peace-themed summer camp in Maine. From secretly snogging her cousin in her bedroom, to sharing more than just a peace duet with an Israeli girl from camp, this story of a young queer woman’s sexual and political awakening–and Bazeed’s first play–was first developed and debuted in a workshop performance at La Mama Theatre in New York City.

From Jordan via her current base of Munich, Amahl Khouri explores the lived experience of queer women in Beirut in No Matter Where I Go. Originally written and performed as part of a conference paper at the American University of Beirut in 2014, this play begins with a group of queer women preparing to give papers on the themes of queerness and architecture to an audience of academics, only to realize that this is a rare opportunity–if they dare–to speak openly about the day-to-day realities of living in the Lebanese capital as a queer woman. Not only that: it is an exposé of the frustrations felt by many in the Middle East at having to explain their lives and selves time and time again to a well-meaning but often ignorant western audience.

Indian writer, lawyer and activist Danish Sheikh explores the ongoing effects of colonial-era legislation on the lives of LGBTQ+ Indians in Contempt. Performed in Delhi just weeks before the reading at the Arcola, the play intercuts an exchange between a lawyer and a panel of judges with the testimonies of ordinary queer Indians as they describe their attempts to live life safely and with dignity in a prejudiced society whose laws do little to protect them. With a deft interweaving of the legalistic, the personal and the poetic, Sheikh takes on the injustices of India’s Section 377, at a time when the clause is facing real-life challenges in the country’s courts.

From Chinese, translator and writer Jeremy Tiang premiered his translation of Taste of Love, an award-winning play by Taiwanese playwright Zhan Jie. Originally performed in Taipei in 2015, the play follows one man’s attempts to grieve in peace following the AIDS-related death of his partner, a high-school teacher. Even as Taiwan legislates for equal marriage, becoming the first East Asian country to do so, this play reveals the prejudices still faced by the LGBTQ+ community in Taiwan, and by those with HIV, in a country, that for all its modernity still remains morally conservative.

The 2015 Taipei production of Taste of Love by Zhan Jie (Photo (c) Creative Society 台灣創作社劇團)

And from Bueno Aires, one of Argentina’s most celebrated contemporary playwrights, Santiago Loza. Originally translated into English for the Cherry Arts (Ithaca, NY) by Sam Buggeln and Ariel Gurevitch, Winter Animals spends one night with a father from the provinces visiting his son in the big city. Their conversation, always skirting around true closeness, is interrupted by the unnerving presence of a naked woman living in the son’s refrigerator. The father, bemused, wonders what this female houseguest means for his seemingly sexually indifferent offspring; but for the son, the woman seems to provide some kind of comfort.

The plays selected, we launched officially, with a modest announcement on social media and a page on the Arcola’s website. The event formed part of the Arcola Queer Collective’s annual season of performances, themselves a part of the Arcola’s Creative/Disruption festival, showcasing work by the theatre’s community companies. We were excited, but as just one small element of a much bigger season, there was no knowing how the event would turn out, or who would come.

But then something began to happen that made us think this might be something special. An email from Danish Sheikh, the playwright from India, telling us he’d be flying in from India to attend the reading in person. Then one from Sam Buggeln in New York State, telling us the same. Then from Mariam Bazeed, also flying in from New York. And from Jeremy Tiang, likewise from New York. And then Amahl Khouri, too, flying over from Munich to be with us. Of the seven plays programmed, all but two would have their writer or translator present, boarding planes at their own expense to share in the weekend. It was humbling.

There was more to come: Amahl also performed in No Matter Where I Go, eloquently introducing the play with a foreword describing the context of its genesis. Mariam, too, performed in Peace Camp Org. Not only that: she supplied the cast with fetching tee-shirts from the original reading in New York, and brought with her the near life-size puppet of “sick Samira,” one of the play’s key characters, to grace the stage too.

We had always planned to hold talks after the performances, but could now do so live with the translators or writers of most of the plays (we were also able to have Jeton join us via Skype from Kosovo). With this unexpected addition to our line-ups, we were able to engage in some fascinating, illuminating, and often deeply moving conversations. The post-show panels, which I chaired, were also generously joined by a number of external speakers.

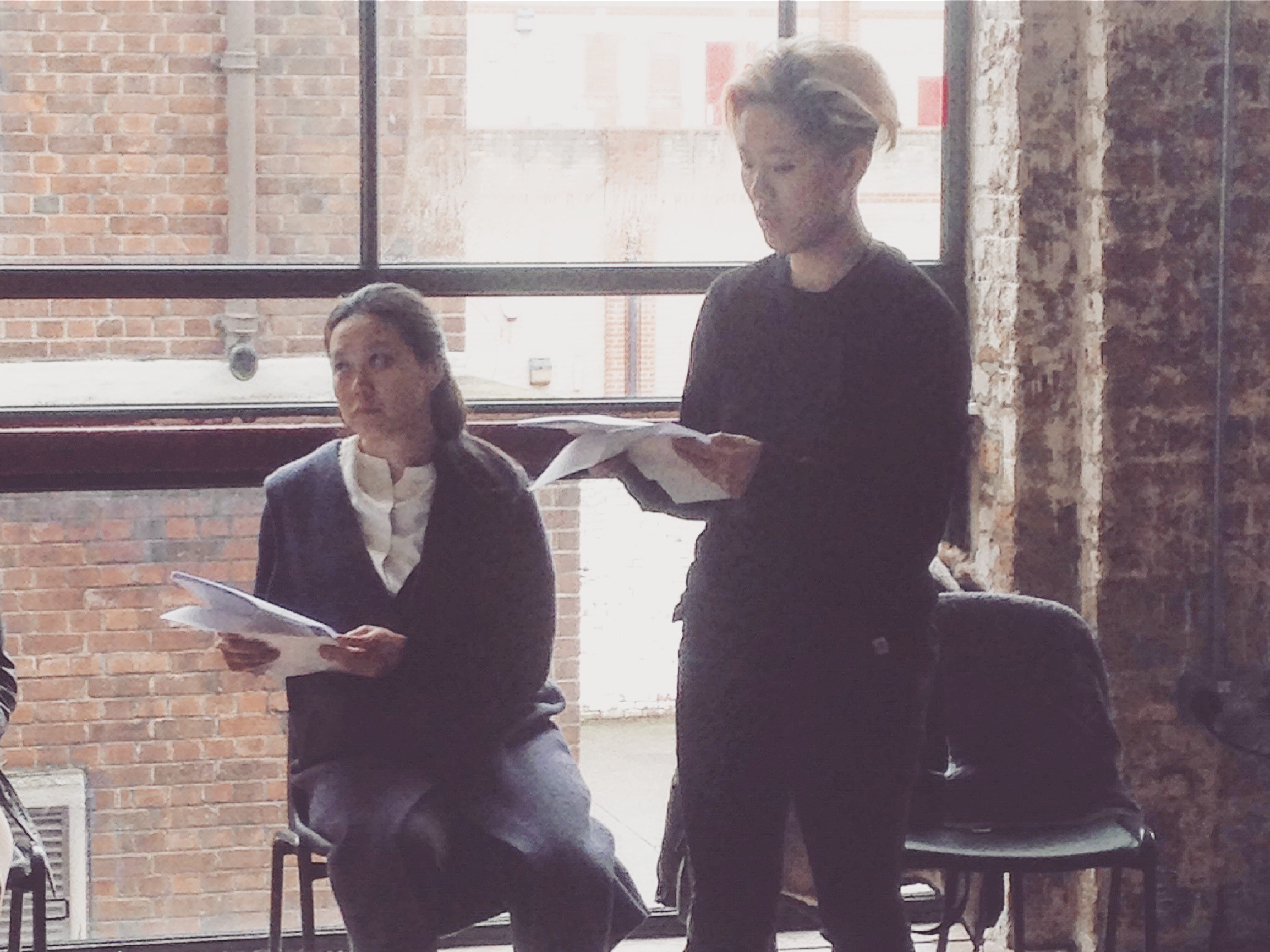

William Gregory (center) chairs a panel with (L to R) Paul Dillane, Tasmine Airey, Jeton Neziraj (on laptop) and Danish Sheikh (Photo (c) Ali Wright)

Following Contempt and 55 Shades Of Gay, we were joined for a discussion on the theme of “LGBTQ+ People and the Law” by Paul Dillane, CEO of the international LGBTQ+ rights organization, the Kaleidoscope Trust. As the writer of Contempt, Danish Sheikh described the origins of the play and shared his detailed knowledge of the current situation in India regarding the fight to strike Section 377 from the statute book. Paul then shared some of the experiences of the Kaleidoscope Trust’s work around the world, especially but not exclusively in the Commonwealth, to challenge homophobia and the legislation that supports it, by engaging closely with local activists and organizations whilst simultaneously calling upon political leaders to take action. The Kaleidoscope Trust works hard, he said, to avoid the attitude demonstrated by the EU staffers depicted in 55 Shades Of Gay. Taking up this theme, Jeton Neziraj described how the patronizing and out-of-touch attitudes of some international political and human rights organizations intervening in Kosovo was mirrored by some theatre organizations too. It was striking, he said, how some cultural entities came to Kosovo to run theatre projects, without noticing that the country already has a long theatre tradition of its own. Talking about her work directing the two readings, Tasmine Airey delighted at the visual and physical potential of 55 Shades Of Gay and talked of the powerful humanity of the testimonies in Contempt.

For the panel that followed No Matter Where I Go and Only The End Of The World, entitled “The Right to Write,” we were joined by Theodora Danek, Writers in Translation Manager at English PEN. Theodora described the two strands of English PEN’s work: on the one hand, defending the human and free-speech rights of writers in any medium throughout the world; on the other, celebrating and supporting writing in translation. Although it may have seemed hard to find immediate connections between plays from such seemingly different worlds, Theodora reminded us that the geographical variations in attitudes to LGBTQ+ people are much more complex than we might assume, giving Austria, her country of birth, as an example. The ideas of the “liberal west” and an “illiberal” elsewhere are quickly challenged when we consider the relatively short distances one has to travel even within a small, seemingly tolerant country like Austria to find pockets of prejudice. Echoing this, Amahl Khouri pointed to another of her plays, She He Me, in which a trans woman from Algeria finds the ignorance and prejudice of Sweden, a country of supposed refuge, too much to bear. In this panel, Amahl also talked about the constant tension of being unable to work in Jordan and having to present work in other countries, perceived as an outsider. Director Hannah Sands, along with some of the cast, also shared some generous personal responses to the play.

Taste Of Love read at the Arcola Global Queer Plays festival (Photo (c) Rach Skyer)

After Taste Of Love, we were joined for a panel on the subject of “Translating Queerness” by Dr. Robert Gillett of Queen Mary University, co-editor of the book Queer In Translation, and by associate director of the King’s Head, Harry Mackrill. After Jeremy Tiang shared some thoughts on the specifics of translating Taste Of Love (among them, the fact that in Chinese the title is a play-on-words of the word “AIDS,” and how in English this could not be replicated without seeming crass), Robert Gillett reminded us of the need to think more deeply about the process of translation: the word “queer,” for example, was adopted into Chinese directly from the English, and pronounced the same, only then to be re-translated back into the same word now. How can a translation account for this journey? He also cautioned against reading or translating plays from other languages based on our own cultural assumptions about the queer experience. Next, Harry, who worked on the National Theatre’s Angels In America, gamely took on my challenge to the LGBTQ+ theatre community to internationalize its programming. The answer, he suggested, was precisely for events like Global Queer Plays to continue; it is ultimately the fringe that influences the mainstream. This prompted a question from the audience about the establishment of an LGBTQ+ theatre canon. As chair, I suggested that the canon exists but has never been cataloged or circulated with the same care as the mainstream canon. But Robert Gillett challenged the very idea of a canon. Why, in the internet age, would the queer community restrict itself to such a tired notion? Director Vicky Olusanya discussed the fascinating process of working on the play with the translator on hand and widened this to talk more about her work directing international plays and the importance as a director of always being open to learning and exchange.

The fourth and final talk followed Peace Camp Org and Winter Animals. In conversation with director Robbie Taylor-Hunt, Sam Buggeln talked about the different ways in which Loza’s protagonist is perceived by different national audiences. While in Argentina the son is generally assumed to be gay, in the US his indifference to the naked woman in the fridge is often seen as asexual. Sam explained that the indicator to Argentine audiences is a reference to the artificial sweetener Sweet ‘n’ Low, which is apparently used widely by gay men in Argentina. In the US, the fact that the son explains to his father that he has no interest in popcorn and that this lack of desire for it is no one’s business but his, is more commonly leapt upon, seen as a code for his asexuality. Mariam Bazeed described the process of writing Peace Camp Org and discussed some of the challenges of finding a theatre willing to take on a play with a strong political undercurrent, even in an ostensibly open city like New York. She also talked about the peace camp itself as a place so self-contained and self-affirming that it risked affording itself an importance that it did not really possess.

Reflecting on this, having chaired the four talks, I wondered if the same was true of our short festival. We had sold out for three of our four sessions of readings. Writers and translators had come from all over the world. There was a great sense of meeting and exchange between practitioners, activists, organizations, and individuals that may not otherwise have happened. But had we nevertheless existed in a bubble?

Closing the final talk, I considered a line from No Matter Where I Go. Describing her life in Beirut, Joelle, the member of the group least willing to share her story, talks of invisibility as a strategy for survival:

“[B]eing invisible is my way of taking control of this! Of my life! Of deciding what happens to my life! To my body! […] Sometimes I wish I could just disappear.”

If nothing else, I hoped that Global Queer Plays had allowed us to be visible. As queer people, wherever we live, we have all, at some point, opted for invisibility as a way to take control of our lives. For some, survival may literally depend on it. For others, it can just be the least tiring option at a given time. But nevertheless, we experience it. If Global Queer Plays did nothing else, it allowed those of us in the room to see, hear, and acknowledge each other, and to be ourselves in an environment that wanted us to be just that. One actor spoke of this event being the first time in their entire career that both their queer and Middle Eastern identities had been allowed to coexist onstage in a single performance. If a two-day space allowed for an experience like this, then even with a bubble of relative safety we may still, by seeing and affirming each other, have created something nourishing, be it to our creativity or to our wider lives, on which to build and with which to be strengthened.

Mariam Bazeed (center) and the cast of Peace Camp Org at the Arcola (Photo (c) Rach Skyer)

And a few short weeks later, as I write this article and we tentatively talk of Global Queer Plays 2019, I learn that these stories will indeed be seen and shared again. After attending each and every one of the readings, theatre publisher Oberon Books has confirmed it will be publishing all seven plays in an anthology later in 2018. Added to the jetting-in of writers and translators, full houses, generous contributions from external speakers, performances from equally generous casts, and in one case a misty-eyed standing ovation, this confirms Global Queer Plays as an event that exceeded expectations on every level.

As one audience member stated, these are plays that deserve to be seen more widely, by audiences of all kinds. I hope our two days in Dalston will be just the beginning. Global queers, play on!

(The organizing team of Global Queer Plays were myself, Rach Skyer, Nic Connaughton, Tasmine Airey, Robbie Taylor-Hunt, Giovanni Bienne, and Alistair Wilkinson, who directed Only The End Of The World. Special thanks are due to Rach Skyer, who produced and coordinated the seven readings while simultaneously performing as the lead in the Arcola’s production of Fine And Dandy, which involved, among other things, singing the George Formby hit When I’m Cleaning Windows in Yiddish while providing their own live accompaniment on a ukulele.)

William Gregory is a translator, occasional actor, and managing editor for the Translation section of the Theatre Times.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by William Gregory.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.