In the end, it’s all about the story. The story you remember, the story you want to tell, and the story you don’t want to admit happened. After surviving a 10-year siege and the final horrific battle for Troy, Idomeneus sails home leading a fleet of eighty ships. A storm arises and every vessel in his fleet but his own goes to the bottom of the Aegean. Why? Why, after all that?

But it’s all about staying alive, so Idomeneus promises the gods that if he and his remaining crew survive, he will sacrifice the first living thing he sees when he sets foot on home soil, the island of Crete. If there is one thing we know about Idomeneus, he is a man of his word; a promise is a promise.

Playwright Schimmelpfennig has unearthed many stories of Idomeneus’ return, and these conflicting narratives are interwoven by a cast of ten who interrogate, challenge and confirm a tale of tragedy, betrayal, and revenge. Revenge playing the bigger part.

What increases the tension and keeps one engaged is how this conflicting narrative is enacted. The ensemble of ten performers mingles amid the black turf of what reminds one of an oil-contaminated beach. They are flung by unseen forces, in the form of sharp, electronic sounds from one end of the stage to the other, falling to rest in tense tableaus. All of this is played out in front of a grey stone wall, with a large crack down the middle. Will Idomeneus defy the gods and spare himself, his son, and his community the shedding of innocent blood, or will he complete the cycle?

Schimmelpfennig offers a few conclusions to clarify the opposing forces of this narrative; the Trojan War began with a sacrifice and ended with one. Iphigenia, Agamemnon’s daughter, was sacrificed so that the Greeks could sail for Troy, and now the first living thing to greet Idomeneus will be his son, a child when he left, now grown and eager to embrace his long-absent father. But is he the first living thing Idomeneus sees as his ship reaches Crete? If so, then a father is bound to a murder. And he too will suffer at the hands of his subjects.

So, what happened on that beach?

And what happened when Idomeneus returned to his long-suffering wife, left alone for ten years? Did he find contentment in the welcoming arms of a faithful companion, or a woman marked with the embraces of his rival.

Schimmelpfennig is less intent on spinning a new narrative or interpreting the old ones as he is on exploring fatal intersections and what they tell us about war and survival. His Idomeneus is a poetic archaeological dig through the maze of myths surrounding one story of the Trojan War.

The ensemble work is excellent as the cast moves from shipwrecked warriors to women searching a beach for corpses of the drowned, to what seemed like denizens of the underworld. Director Alan Dilworth has done an excellent job of shaping the production, assisted by Lorenzo Savoini’s inspired set, lighting, and video design.

It’s also hard not to see the dust-covered survivors of yet another bombed-out neighborhood in Syria in Gillian Gallow’s costume design.

And what about those startling sound effect? A few times I actually thought a careless cell phone was beeping out from the audience, only to realize it was the dissonant siren call of some god telling his minions to line up and hear another pronouncement of fate. Debashis Sinha’s eerie sound design is another component of the exceptional production elements that interpret Schimmelpfennig’s multi-layered text.

I particularly liked the way the way choreographer Monica Dottor worked with the ensemble so that they appear to plaster themselves against the set’s cracked stone wall, clinging in the position like so many primitive etchings. And were those projected shadows that haunted the actor’s movements? I swear I saw Hughes’ shadow walk away from him at one point. Or were my eyes deceiving me? Is it possible you may not know the truth of a story that unfolds before your very eyes? (There is a slightly puzzling sequence at the end as we move through time, very quickly, in which the characters dance like mad revelers at a Bacchanalian bash.)

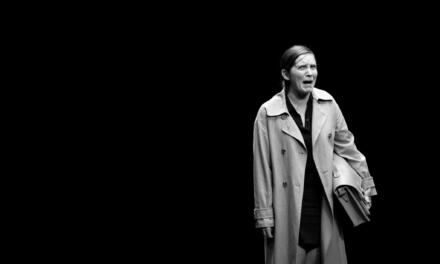

Special mention to Stuart Hughes, as Idomeneus, for his fierce vulnerability, and Michelle Montieth and Kyra Harper in various roles, but this is an ensemble effort, by those onstage and those behind the scenes, that grabs a high bar with assurance.

Idomeneus is returned home from the Trojan War, only to find that a lust for violence is now his constant companion, as it is ours. Aghast at the cruelty inflicted on the slaughtered sons and daughters in current wars, we need not turn our eyes to the past.

This article originally appeared in Capital Critics’ Circle on March 13, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Laurie Fyffe.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.