It was exactly ten years ago that Big in Belgium – a season of work from Flanders – was first presented at the Edinburgh Fringe. This panorama of eight new experimental pieces came on the back of the unexpected Edinburgh successes of the Ghent-based collective Ontroerend Goed, with their conceptual and cosy works Smile Off Your Face (2007) and Internal (2009) and their triumphant work for teenagers Once and For All We Are Going to Tell You Who We Are So Shut Up And Listen (2008) and Teenage Riot (2010). Big in Belgium returned for the following few years, in the capable hands of the Ontroerend Goed’s producer David Bauwens, often presenting at the cool new venue on the Fringe map, Summerhall. Then everything went on pause for a while around the Covid pandemic. But after the hiatus, ten years after its debut, Big in Belgium is back again, this time at a new location, Zoo Southside.

The Big in Belgium 23 offering includes one piece from Ontroerend Goed – Funeral, one piece by Wunderbaum’s Marleen Scholten, La Codista/ The Queuer and two pieces from another Belgian regular SKaGeN – The Van Paemel Family and Sneakpeek Shadow Game.

Perhaps the most distinctive aspect of the Belgian theatre scene is indeed this spirit of togetherness which means that the individual contributions do add up to something greater than the sum of their individual parts. Both Wunderbaum and SKaGeN are collectives that are represented here by solo shows or works without conventional choruses of bodies on stage.

Sneakpeek Shadow Game. Press Photo.

SKaGeN’s Sneakpeek Shadow Game – a piece formerly known as WatchApp – is conceived by Mathijs F Scheepers and created by Korneel Hamers and Elisa Demarré together with the rest of the company, to be experienced on the audience member’s mobile phone via text messages and videos delivered through a specially designed app. The individual audience members can follow real time for a week the trials and tribulations of a sixteen-year-old refugee SK (Sanjid Kahn) on his journey from Afghanistan, across the Balkans and into Europe. The scenario which is based on three years of actual documentation collected from 2019 to 2022, is envisaged to have three week-long parts, and Shadow Game is only part 1 of the trilogy. While it does not take place at all in a conventional performance venue, Shadow Game in fact permeates the daily life of the mobile phone user in a similar though much more thought-provoking way than most other apps would do.

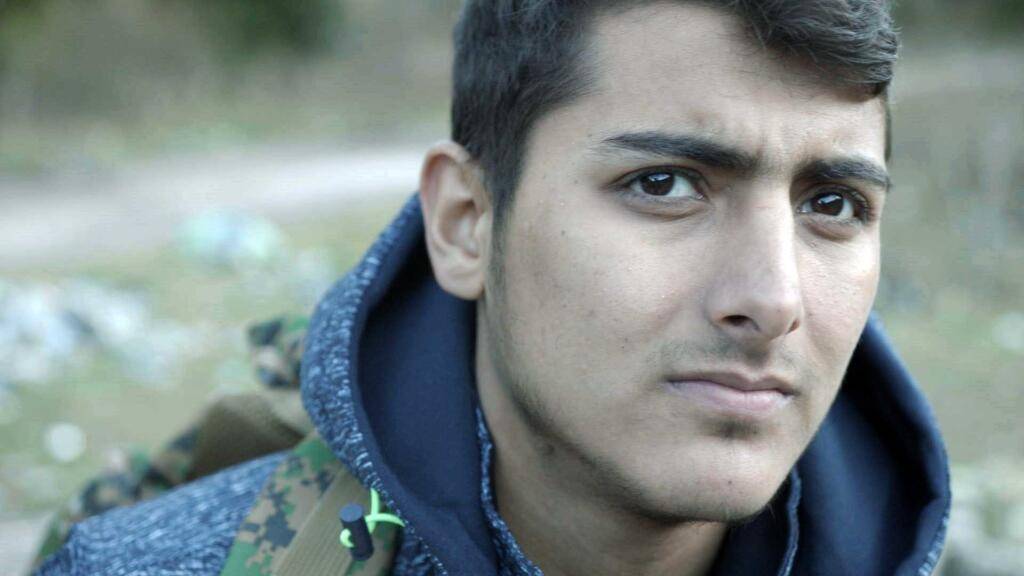

The Van Paemel Family. Press Photo.

At the other end of the scale, SKaGeN’s Valentijn Dhaenens – previously seen in Edinburgh with his experimental solo shows BigmoutH, SmallWaR and Unsung – unexpectedly tackles a play from 1903 The Van Paemel Family, written by the Flemish naturalist author Cyriel Buysse. The play charts the hardships of a Flemish farming family at the turn of the twentieth century, featuring the usual tropes of a renegade son, wronged daughter, cruel and unkind master, stoic and loving mother, dying child, and bitter and unyielding father. Dhaenens’ rereading of this play is aided by a technique he developed in his earlier work SmallWaR, where he created digital alter egos of himself on screen in order to add seven more characters to the action on stage. In continued collaboration with the video artist and editor Jeroen Wuyts, Dhaenens refines this method further so to create believable interactions between characters set against metaphorical backdrops. Thus in each of the four acts of the play, he takes on a single character – often one involved in a kind of conflict with the others – which he plays out live on stage against pre-filmed and projected versions of up to 12 others, all played by himself. Though it takes a few minutes to get accustomed to this new way of watching theatre, the result is quietly mesmerising and certainly unique. Given the amount of technical innovation on stage it is perhaps also relevant that the classic play chosen by Dhaenens is a story about change and the way in which it can produce a variety of conflicting responses.

By contrast, Marleen Scholten’s La Codista/ The Queuer, which incidentally takes place in the same space, deals with a similar kind of crisis through absolute scenic minimalism. Scholten is alone on stage, in a neutral costume, and almost completely static throughout her show. She performs the act of waiting in a queue – a brand new occupation actually invented by Giovanni Cafaro from Milan when he began waiting in line for others in exchange for money. Ostensibly emerging out of the stark social inequality between those who are too busy to do their own chores and those that cannot find a job despite having a master’s degree, the piece is clearly a comment on neoliberal capitalism in the 21st century. Additionally Scholten’s script makes a subtle but well observed parallel between this kind of a job and the work of an actor: ‘I imagine I am the person I am waiting for – maybe that’s why I’m good at what I do’. Much of it is a stream of consciousness chatter that one might imagine working well on the radio too, well observed and meditative in tone, it builds to a witty and provocative punchline.

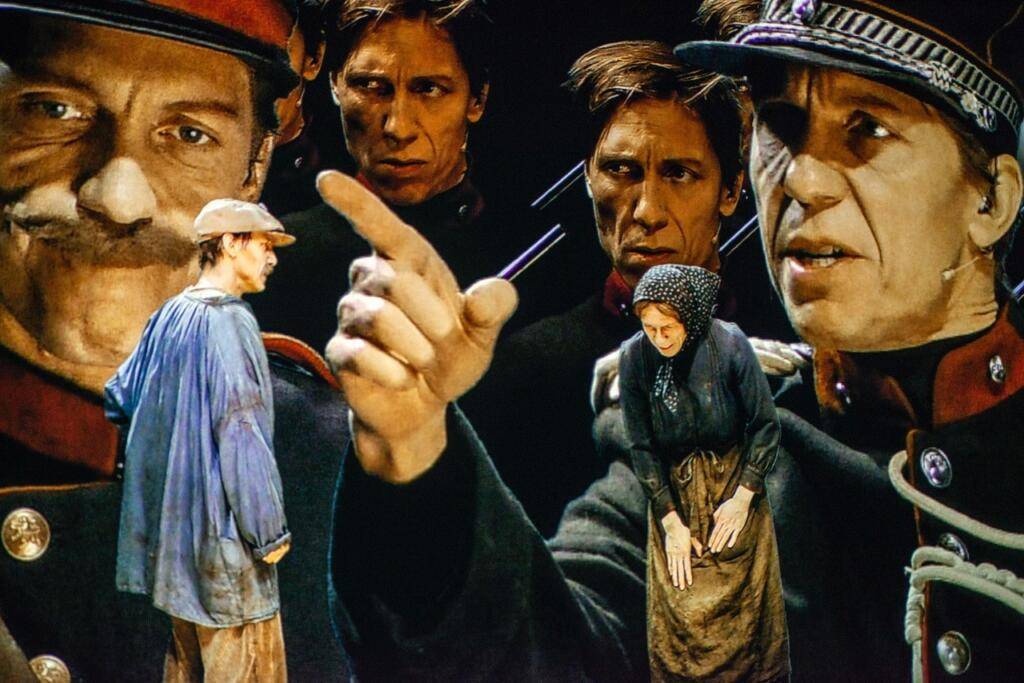

Funeral. Photo by Ans Brys.

The most eagerly awaited stars of the Big In Belgium season, however, must be Ontroerend Goed themselves, whose latest show Funeral is sold out days in advance. Famous for confronting audiences with experiential contemplations of what it means to be an audience, dating, democracy, global economics, and climate crisis, this latest piece is a theatrical re-examination of rituals of mourning. Created by the ensemble under Alexander Devriendt’s direction and enhanced by Joris Blanckaert’s music and Sarah Feyen’s lighting, in the aftermath of the pandemic, the piece deals with grief in a number of insightful ways, none too dark or overly taxing, but mostly appreciative of simple comforts that are otherwise easily overlooked in the depths of sorrow: a handshake, a reminiscence, a choral chant, sitting together, building a shrine, merely being mindful, saying goodbye. At times it is reminiscent of the company’s earlier work, particularly the solo show World Without Us inspired by the Voyager spaceship’s departure from the solar system together with a time capsule of messages packed in 1977 to document the human species. It is not difficult to see how Funeral, on the other hand, has emerged from the more down to Earth traumatic global experience of social isolation, and it certainly casts a new light on familiar aspects of loss experienced at the time. What it does in addition is a staging of transcendence – a relief of transformation, a lightening of spirit. It is a kind of experience that defies verbal articulation – and that is its point: all it needs is a simple act of joining in, of being together.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.