“I do not know how to write,” Agnieszka Kazimierska’s Katie tells her audience. At this moment—approximately a fourth into the play—her viewers bear witness to Katie’s paralytic attempt to write to her lover, away at war. Her hand hovers above a piece of parchment; she worries at her lip; she smiles, falters, laughs, gasps. She cannot write, and she turns to distraction within her garden of cherry trees, vaudevillian reenactments to fight off flashback.

The statement, touching in its delivery, is ironic when considering how skilled Kazimierska herself is at crafting a solo performance. Katie’s Tales, presented as part of the 15th Annual United Solo Theatre Festival, is a physical verbosity, following a young Eastern European woman both within and without time as she awaits the return of her lover. Kazimierska is Katie, trapped in an Edenic paradise surrounded by sinister remembrance. She is also G and Mary, Katie’s steadfast, foreign-born servants. She is also Katie’s drunken Uncle, a convoluted subversion of misogyny. And she’s a most-terrifying vocalization of Dictatorship and History (yes, capitalization included). Each, she becomes with deft navigation of interwoven prose and song.

And more, in fact. Prose becomes poetry becomes song becomes syllabic repetition: if it’s a way the human body can communicate emotion, Kazimierska utilizes it. The jumping has a rather avian effect, or perhaps gossamer or Pre-Raphaelite, something befitting a play rife with written flight and oceanic metaphor. Katie flits from unsurety to groundedness as Kazimierska transforms from person to person; the absorption, for both, of History in all its trauma leads to an inherent inability to stay in one place for too long. Kazimierska’s breaths become a cry. Her transitory refrain, of Polish words never translated, is memory of the most dear and painful.

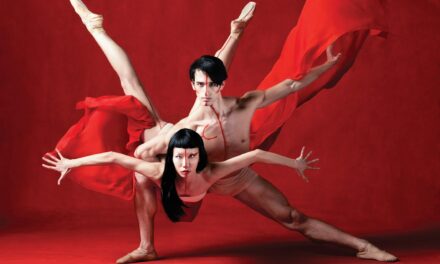

Agnieszka Kazimierska in “Katie’s Tales.” PC: Nikita Chuntomov

Katie’s tale only works because of Kazimierska’s willing vulnerability. From the moment lights arise, her eyes are piercing, face open, a necessary confrontation of the performer/spectator separation and an invitation into her world. Sparse set decoration and simple white clothing make for no wandering eye. The gaze is on Kazimierska with constancy. She meets what could be intimidating, and does not flinch. Through the physical shifts of posturing and carriage, the verbal contrast of lilt and command, it is this meeting that remains the most stunning. I found myself thinking, more than once, that I had never seen as actor so open to their audience. She had no barricade to protect her. She cried without wiping her tears; she sang without fear of the crack; she paced and snapped and screamed and laughed with no regard for her physical state. Her courage to, in alternation, stand in stillness and shriek in pain made Kazimierska’s Katie one of the most human characters I’ve seen onstage. “The splitting was weird, but it was like a salvation,” says Katie of falling in love. The same can be said of Kazimierska’s performance.

Katie’s Tales grows ever timelier. At my point of viewing, in Fall of 2023, Katie’s talk of religious persecution, of G and Mary (themselves Biblical reference) thrust out of their Middle Eastern homes, came only days after Hamas and Israel’s unrelenting attacks on Gaza. Katie’s reliving of loss, of another’s memory of assault, comes after years of war and genocide throughout our world. Her unrelenting love gives us both a picture of descent and of hope. It’s a message needed, I believe, as long as it is accompanied by action.

To learn more about Katie’s Tales, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.