Eugene Ionesco Theatre of Moldova participated in the 23rd Cairo International Festival for Contemporary and Experimental Theatre this week with the monodrama Last Night in Madrid, drawing audiences into the story of Jacqueline Roque, Pablo Picasso’s last wife.

The troupe has a memorable history with Egypt. The first of several visits was in 1992, after they had journeyed four days by bus to perform Waiting for Godot at the festival, then known as the Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. At the time the state of Moldova was just two years old, having just separated from Romania. “I think no one in Egypt had even heard about Moldova then,” one of the troupe’s actors, Petru Vutcarau, tells Ahram Online. They left right after their performance, feeling their presence was negligent, and it was only when they reached home four days later that they realised they had won the grand prize for best performance, and Vutacarau best actor. At the time the experimental theatre festival was competitive, and they ended up winning the year after’s Best Actor for Exit the King, and then again in 2001 Best Actress for Medea.

Earlier this year they performed The Bald Soprano at Bibliotheca Alexandrina during the contemporary theatre festival. They return again with actress Ala Mensicov performing Last Night in Madrid, directed by Vitalie Durcec.

The artist’s women come to life

The troupe premiered the play Last Night in Madrid in 2004 in Romania, and went on to stage it widely internationally.

The script is a chapter from Irish writer and playwright Brian McAvera’s text Picasso’s Women; a series of eight honest and intimate one-woman plays about each of the painter’s wives, mistresses, and muses. McAvera’s highly successful 1999 script was translated into fifteen languages, providing an account of the prolific artist’s life through the eyes of his women, the muses he often abused. The monologues don’t shy away from showing Picasso’s dark side, painting the artist as a libidinous, selfish and often abusive lover, with occasional tenderness at his own convenience.

The troupe selected Jacqueline Roque’s monologue for what they saw in her unique relationship and position in the painter’s life. “I really liked her story, though it has a lot of suffering. Jacqueline was quite special to him, and he really loved her,” Mensicov tells Ahram Online. Jacqueline was widely viewed as a cleverly scheming ‘other woman,’ and the enigmatic one who got the painter to settle down.

In a sense, she was the heart of a Russian doll that was Picasso’s relationships. Their relationship began during Picasso’s companionship with Francoise Gilot from 1944 to 1953 who was the mother of two of his children, which was already within his first marriage to Olga Khokhlova, mother of one of his sons. When Picasso met Jacqueline, she was 26 and he 72. Khokhlova died in 1955 and Picasso married Jacqueline in 1961. Their marriage lasted until his death in 1973. Thirteen years later, Jacqueline shot herself.

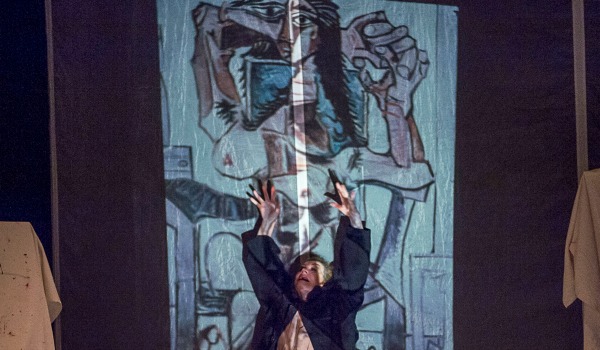

Jacqueline’s monologue is told to the audience between suicide attempts; starting her life with her first husband, until her tragic ending. From beyond the grave her prominent and haunting image lives in over 400 portraits of her by Picasso. McAvera’s text gave her a voice, and with Mensicov ‘s performance she is fully resurrected.

The one-woman show

Mensicov’s Jacqueline is a powerful woman with deep insecurities. The character is a complex one, with very few historic accounts documenting her, making the actress’ role all the more challenging to depict multiple psychological layers. Mensicov fleshes out the inner workings of a woman determined to “be indispensable,” and how she justifies her plans to control, which often contrasted her submissive actions in the story she shares.

From the first words she speaks she is balancing between a desperate widow that is almost pathetic, and a smooth operating, possessive seductress at work who is almost cunning. “Because the play is simple on stage, I can express easily the different aspects of her and her many stages. Sometimes she is sensitive, other times she is strong,” Mensicov says.

The set harmoniously looks like one room in an artist’s house, but serves as several spaces arranged like points on a half circle; a set-up with clay pots depicting the pottery shop where Jacqueline worked and met Picasso, an easel with paints depicting a studio, a ladder with clothes hanging on it, and a rocking chair for a living room. Upstage there is a transparent screen. Standing behind it, she would be performing scenes alongside her shadow, caused by a backlight.

Mensicov’s movements encompass the stage, as she moves across the micro-sets with the story. At times she is a powerful imposing figure, climbing to the highest step of the ladder, other times she is a sensual, lithe dancer on cue with the music, and sometimes she is weak and collapsing to the ground.

Most of the performance plays out in a high emotional state, with some lower points that don’t last long. But the absence of gradual build-up is justified by the fact that it already opens at a high point (Jacqueline’s suicide attempt) and already has a hysterical sense of urgency to begin with. The emotions are high from the very start while the events within serve to justify those already well-crafted emotions.

She accentuates her story with different props, painting in red the year in which Picasso left Francoise, picking up a Spanish shawl for their time in Spain, drinking from the wine glass in his studio. She even changes her costume on set, after having taken her dress off while describing an incident of undressing for Picasso. Though Mensicov’s performance is enough to visually engage the audience, the play in Romanian very much relies on understanding the monologue itself to be enjoyed by a foreign audience.

An English translation was projected on a screen suspended from the ceiling. One technicality that was challenging was how the small theatre made it difficult for viewers to look at the screen without missing the action on stage. A larger stage would have placed the screen further upstage and made it more comfortable. The widow uses another projector to show slides of paintings by her deceased beloved, obsessing over how many portraits are of her. The play runs like one long shot, with scenes from a decade fluidly melting into one another.

Lighting also serves to heighten Mensicov’s monodrama. Warm yellow lights were at times cast on the set with Jacqueline in relative darkness, and other times flooded her. In certain moments red backlights would spill on the transparent screen, flooding it in an urgent warmth expressing passion, jealousy, anger, and eventually death. Death is accompanied by the sound of thunder and violent storms. Other sounds come in to match scenes, such as a simple guitar soundtrack and music from the different countries Jacqueline mentions, France and Spain.

Richard Dorment wrote in The Telegraph that when Picasso bought the Chateau de Vauvenargue [where the play is possibly set]: “At once, his palette darkened to ochre, dark greens, sombre reds, and Spanish blacks. And so, almost by osmosis, Jacqueline became associated with these forbidding colours, the colours of approaching death.”

The audiences at El-Ghad theatre expressed their delight with a standing ovation, the highest praise the troupe can receive now that the festival is no longer competitive.

This article was originally published on Ahram Online Arts and Culture Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Soha Elsirgany.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.